RMB – internationalisation is not over

Paul Mackel, Joey Chew and Jingyang Chen

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2024 survey results

RMB – internationalisation is not over

Managing the tides: the dynamic history and future challenges of Korea’s foreign reserve diversification

Interview: Jonas Stulz

Reserve management at the National Bank of Slovakia

The NBP’s gold purchases – a view from the risk management trenches

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

- Foreign holdings of RMB assets have moderated since 2022, but this alone does not mean RMB internationalisation is stalling.

- The use of RMB in global payments and public financing is rising on the back of China’s trade and financial linkages.

- RMB swap lines, trade agreements and the Belt and Road Initiative should support a higher level of internationalisation.

The mainland Chinese economy has faced major challenges in the last few years, including geopolitical tensions, strict Covid-19 pandemic controls, as well as an ongoing property sector slump and local government debt restructuring. In mainland China’s financial markets, the last two years have also been a period of renminbi depreciation, falling interest rates and stock market weakness. Some may wonder if all these have undermined the RMB’s global standing.

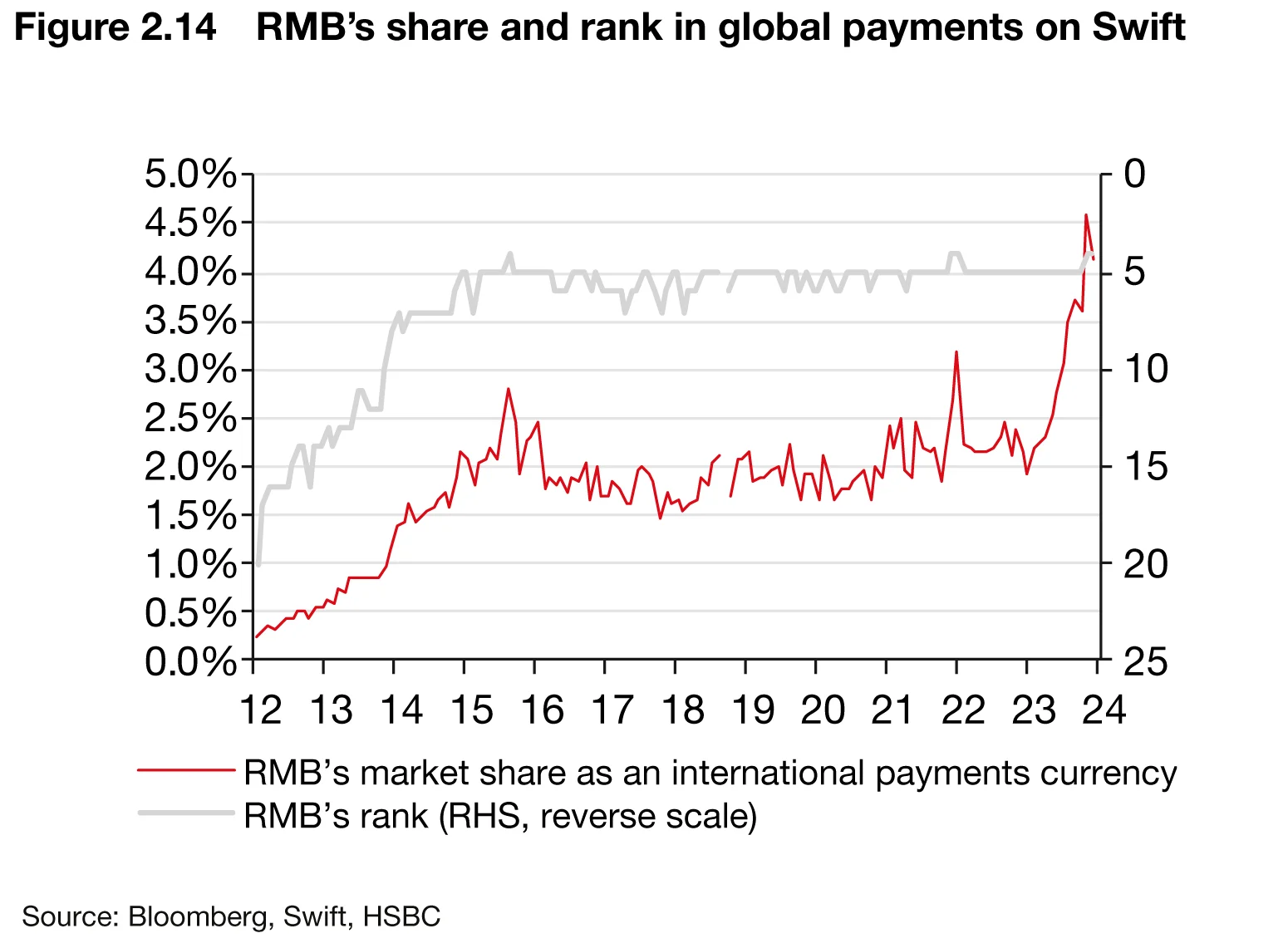

But RMB internationalisation is multi-faceted. While the RMB has not made much progress as a reserve currency and an investment currency, its role as a settlement currency has expanded. RMB settlement accounted for 26% of China’s total goods trade at the end of 2023 – a jump from the 10–15% range it was languishing in during 2017–21. The RMB’s market share in global Swift payments also surged in 2023, from 2.2% in December 2022 to 4.5% in February 2024. The RMB replaced the JPY as the fourth most active currency for global payments in late 2023.

The RMB is also developing as a financing currency. Alongside trade settlement, the RMB has naturally gained a little market share in global trade finance – 5% in late 2023, from less than 2% two years ago. But what is more interesting is that, in recent years, Beijing has become an international lender of last resort. The government’s overseas lending portfolio, which used to be dominated by USD-denominated infrastructure project loans, is gradually shifting towards RMB-denominated emergency liquidity support. This can serve multiple purposes: helping borrowers with loan commitments to China avoid defaults; encouraging greater use of the RMB in cross-border transactions; as well as laying the groundwork for the RMB to grow into a more significant reserve currency over time.

For the RMB to achieve a higher level of internationalisation, empirical studies suggest that deeper trade and financing links, as well as better infrastructure for RMB settlement, will be key. The People’s Bank of China’s RMB swap lines and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) will likely continue to be influential. In addition, policy-makers can develop incentives to offset switching costs away from the USD and other currencies. E-CNY also has the potential to provide significant efficiency gains in cross-border payments.

Some scholars argue that a degree of stability and predictability in terms of the RMB’s conversion into the USD can also be important to make the RMB more widely accepted. We think this view provides another angle to help understand the PBoC’s current foreign exchange policy settings, such as its strong desire for USD-RMB stability and its preference for banks’ ‘shadow’ intervention while preserving its own FX reserves.

Has the RMB become “uninvestable”?

Some media outlets have been reporting about how “uninvestable” the RMB has become – for example, Reuters on February 9. The Wall Street Journal also reported on November 17, 2023, about a rise in the popularity of “ex-China” benchmark indices for foreign funds to track.

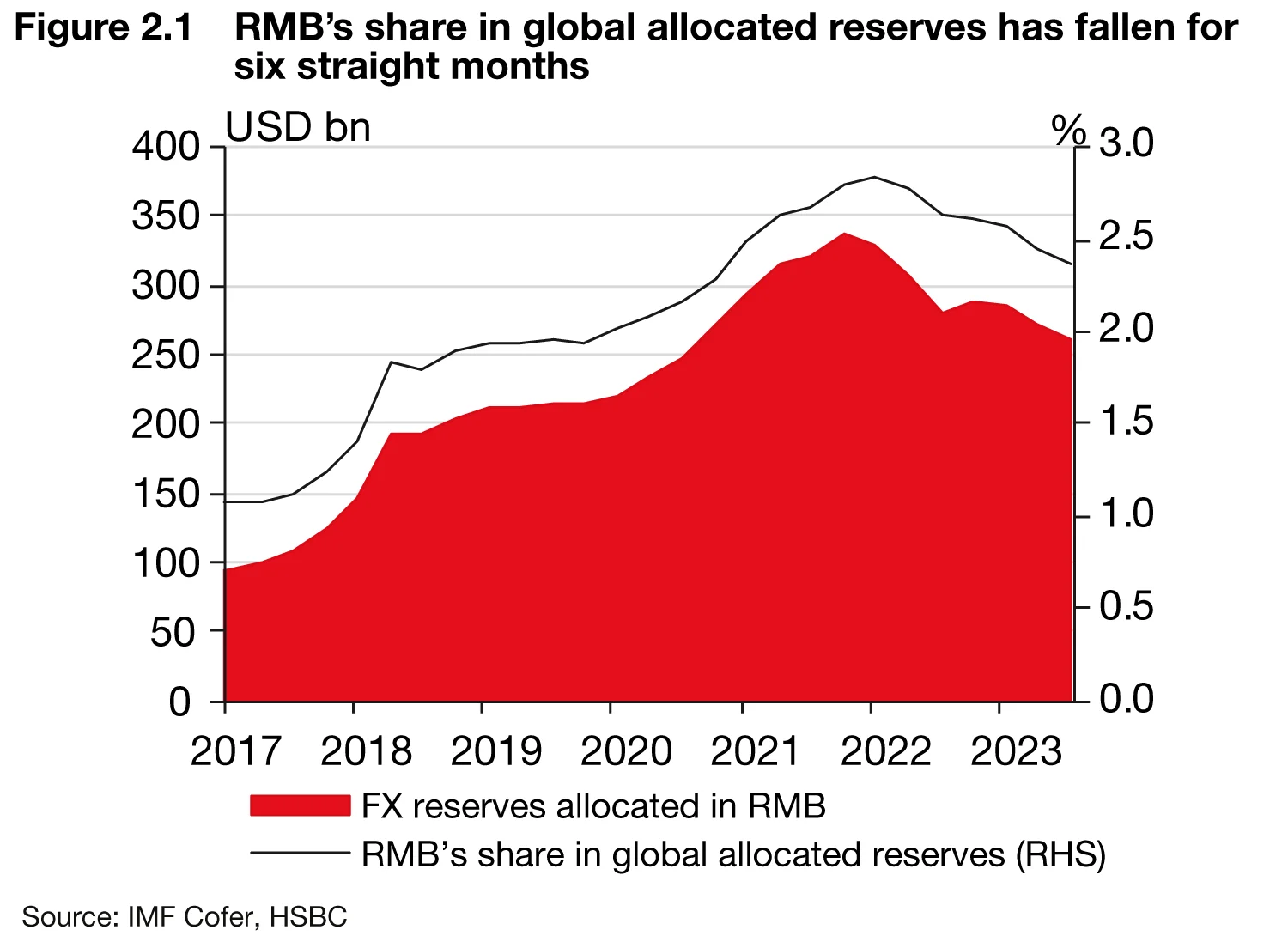

Indeed, the RMB’s global role as a reserve currency (for the public sector) and investment currency (for the private sector) has not made progress since 2022.

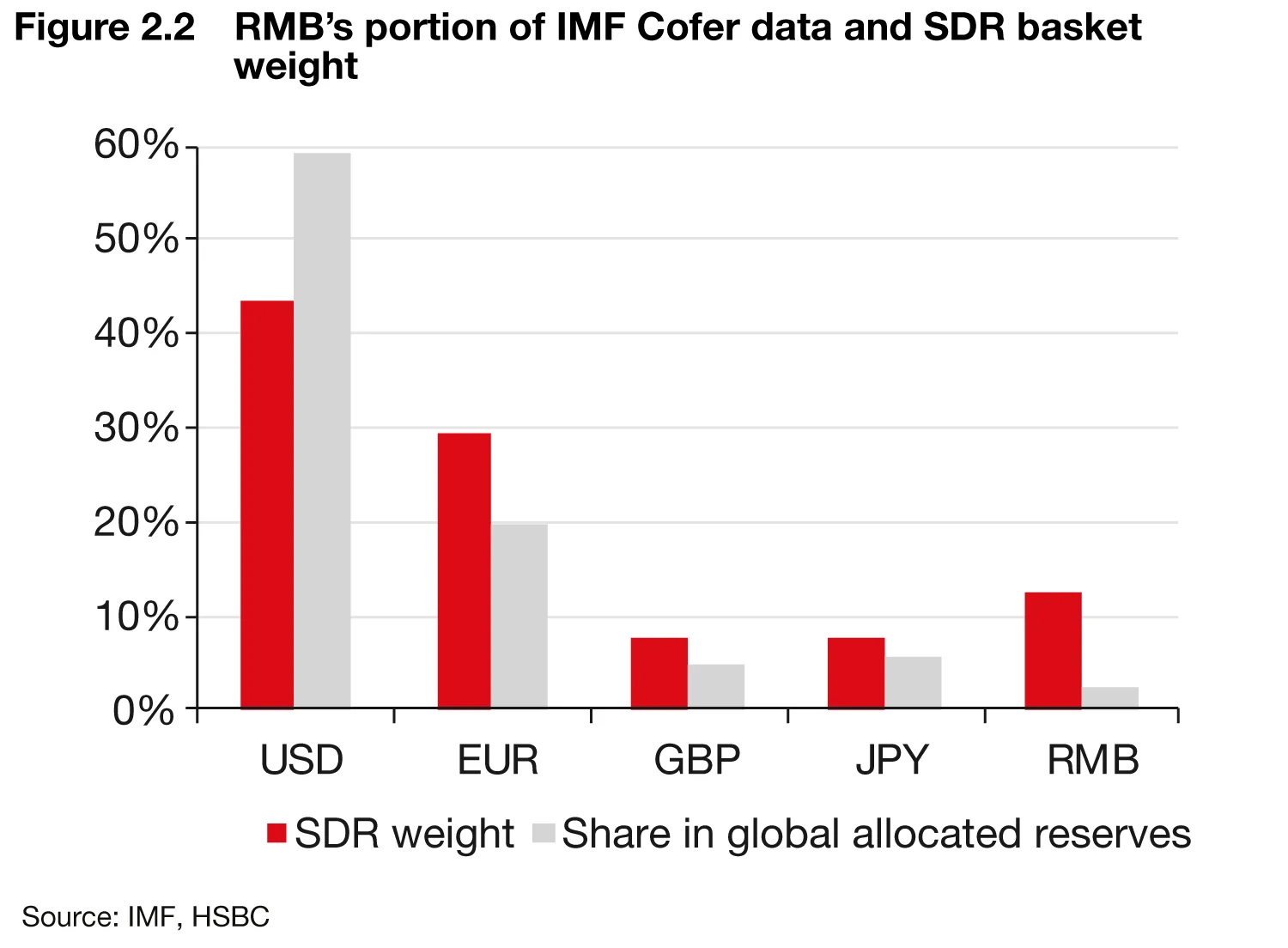

- The International Monetary Fund’s Currency composition of official foreign exchange reserves (Cofer) survey suggests that the RMB’s share of global allocated reserves peaked at 2.83% in Q1 2022, and has reduced by 0.46 percentage points since then, as of Q3 2023 (figure 2.1). Allocated reserves to the RMB have fallen by 245 billion yuan since end-2021. This was the first time global central banks sold RMB since the RMB was included in the IMF’s special drawing rights (SDR) basket in 2016. The gap between Cofer allocation and SDR basket weight is the largest for the RMB, compared with the other four currencies in the SDR basket (figure 2.2).

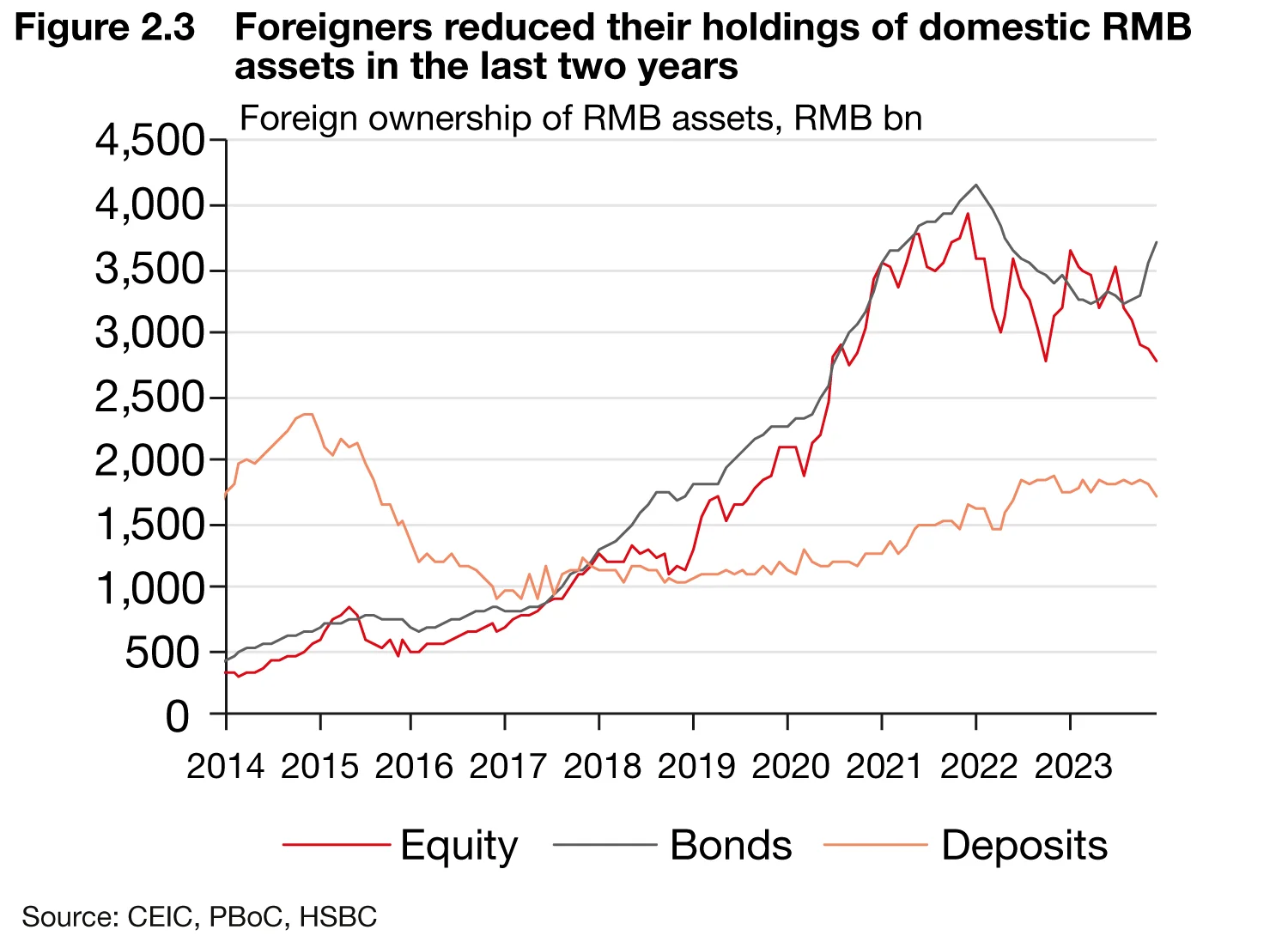

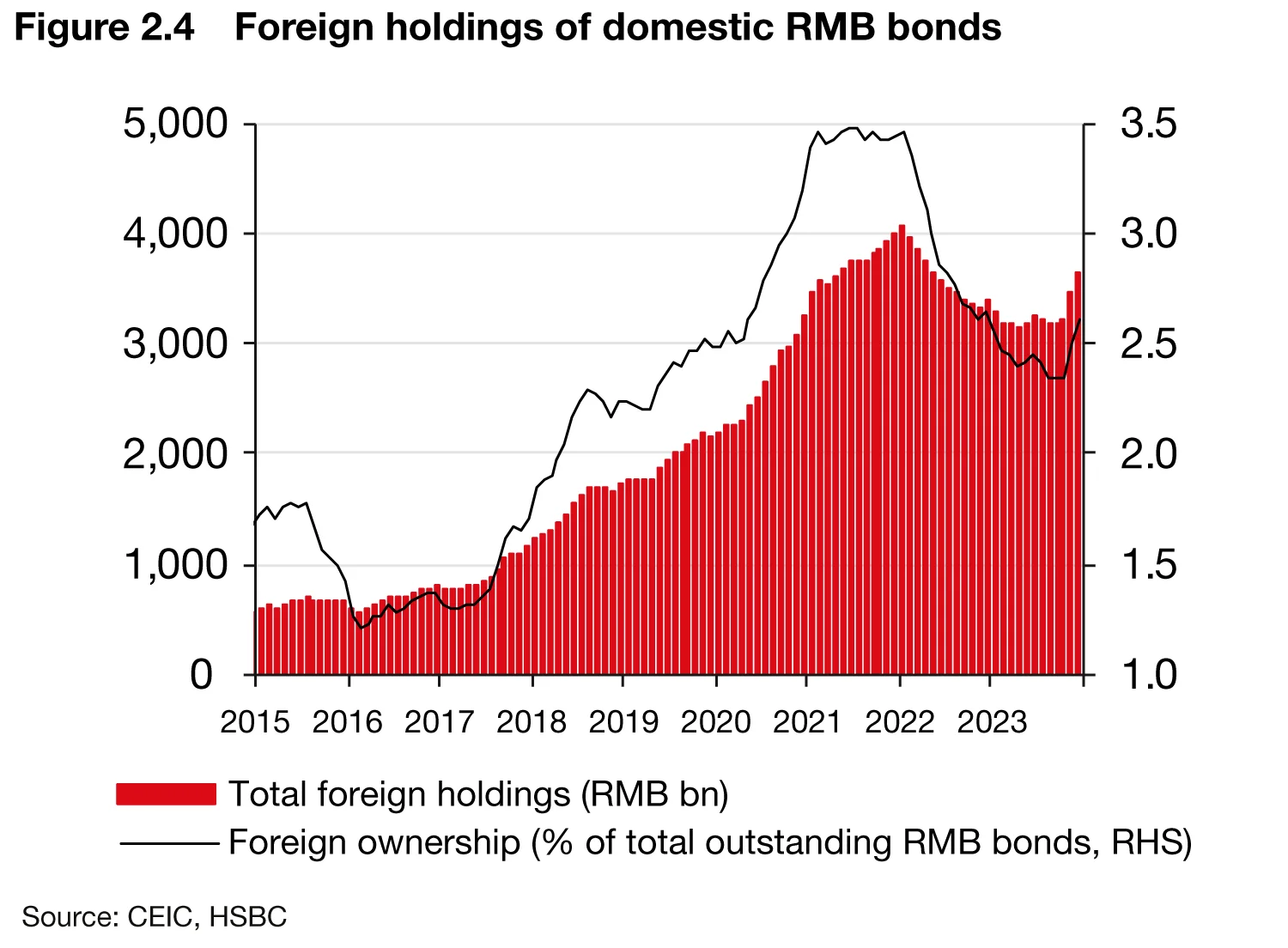

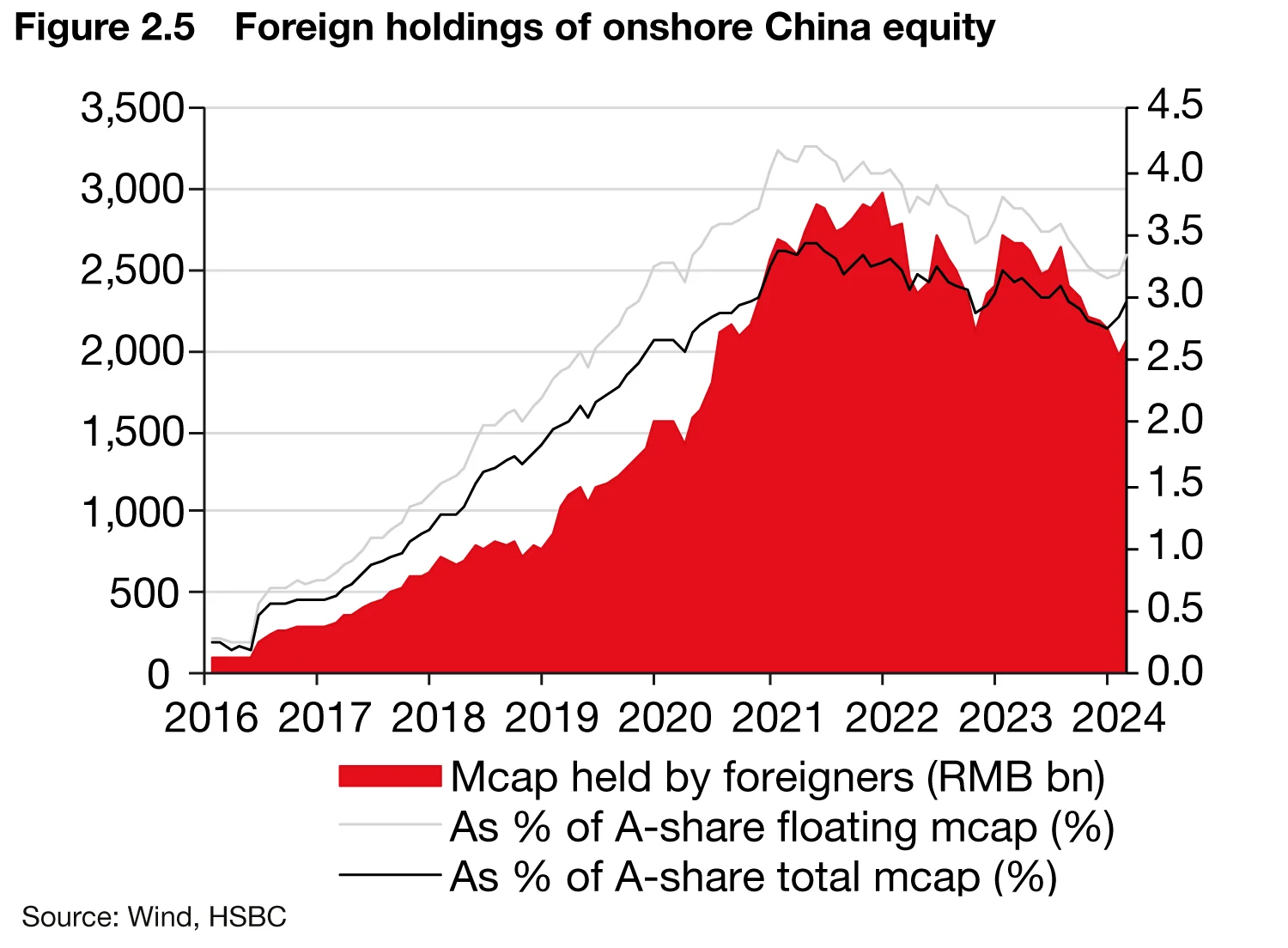

- Foreign investors have been mostly selling their RMB portfolio assets since early 2022 (figure 2.3). Bond investors sold off almost one-quarter of their onshore RMB bond holdings between February 2022 and August 2023, although they have resumed buying on a currency-hedged basis since October 2023 (figure 2.4). Equity investors sold 157 billion yuan ($21.6 billion) of their A-shares via the Northbound Stock Connect channel between April 2023 and January 2024 (figure 2.5).

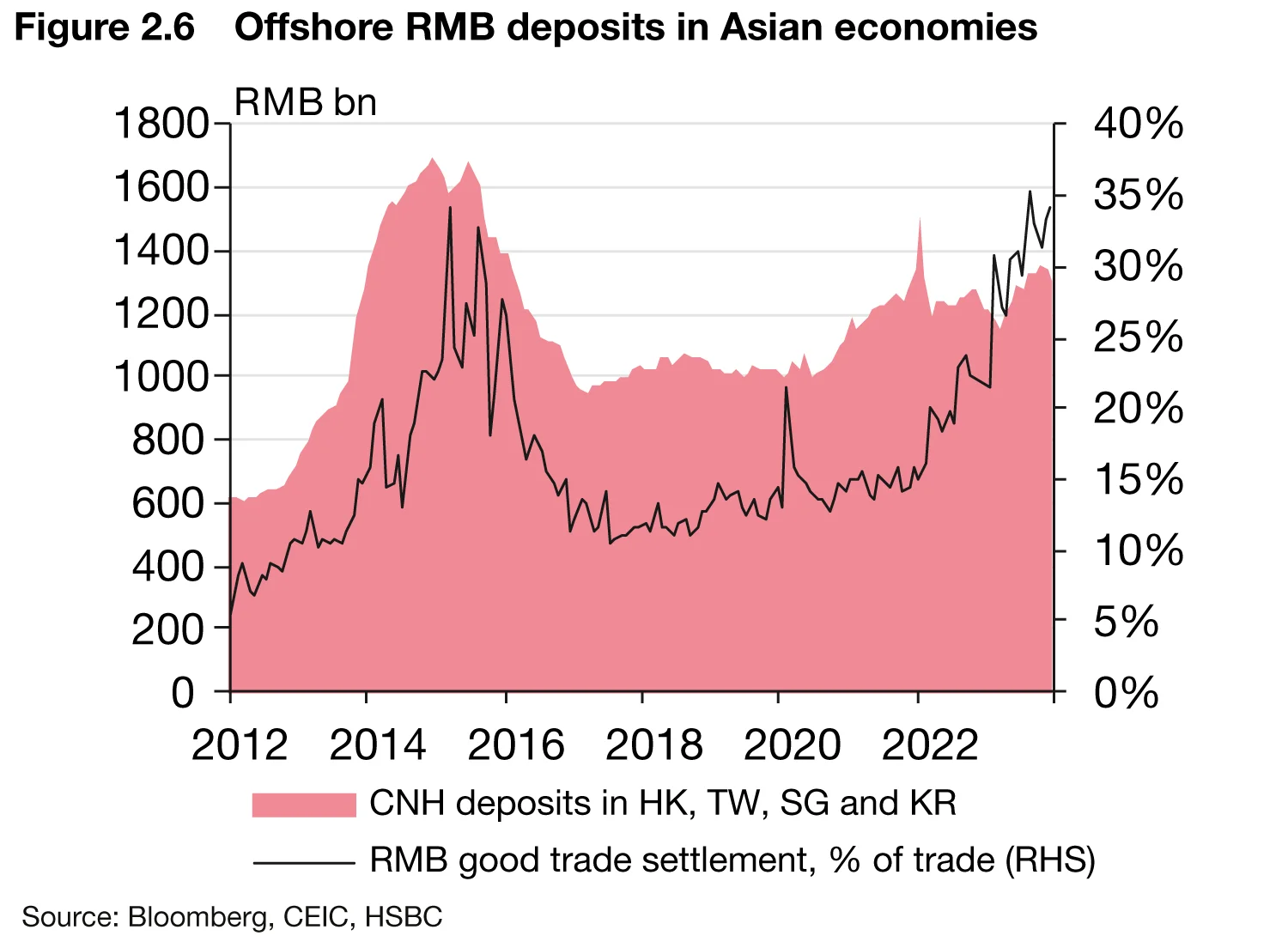

- A composite measure of the offshore pool of CNH deposits in Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea has been little changed in 2022 and 2023 (figure 2.6). This is despite the large amount of RMB-denominated cross-border outflows of 859 billion yuan (or $118 billion) between July and October 2023, which far exceeded the net outflows recorded through the RMB-denominated portfolio channels (Stock Connect – $39 billion; and Bond Connect – $17 billion). It is possible that some of those excess RMB outflows had little to do with RMB internationalisation, but more to do with market participants trying to overcome onshore constraints when USD-CNY was trading close to the top of the band.

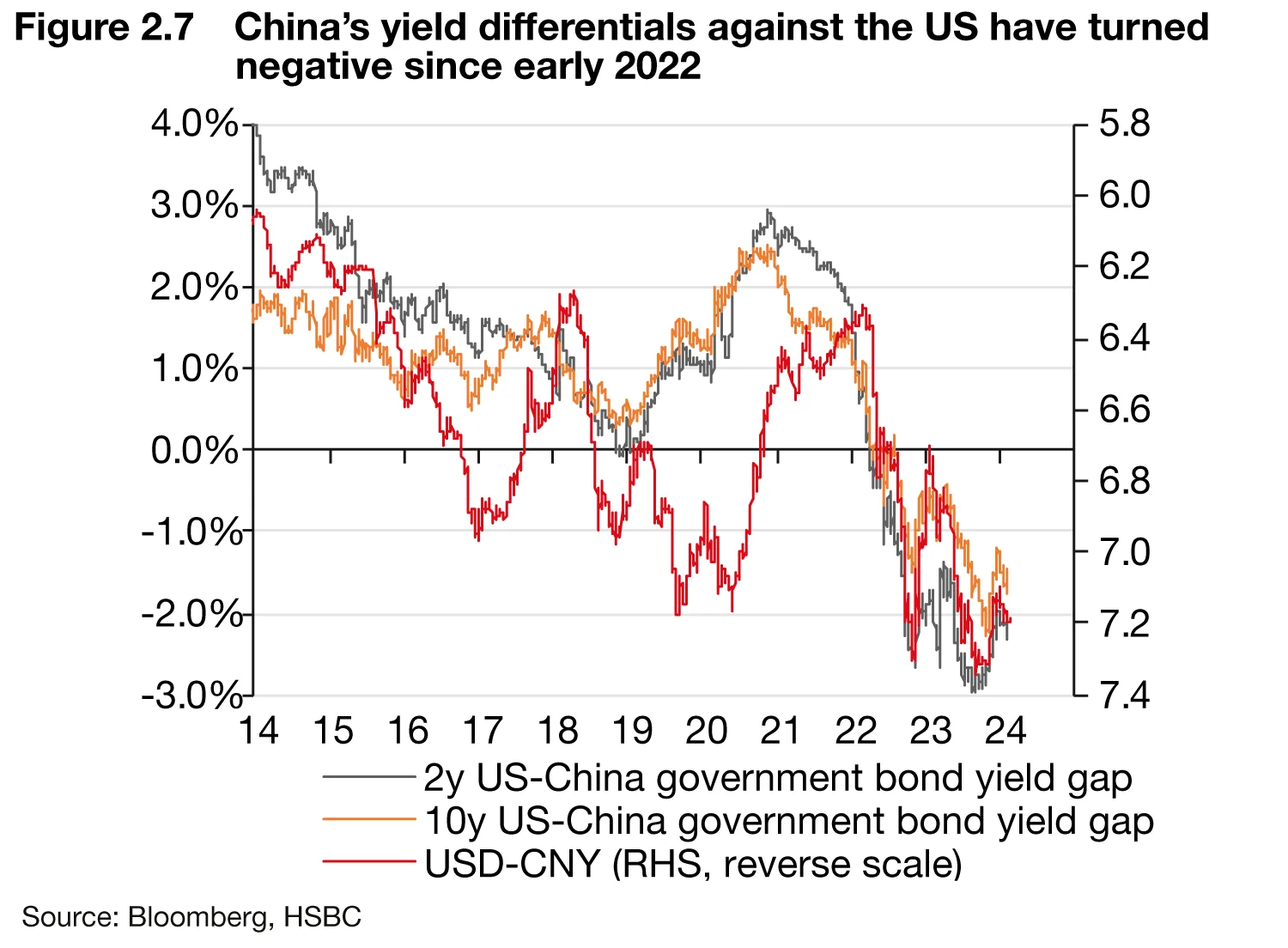

There are cyclical reasons behind foreigners’ reduced interest in RMB assets. The divergence between mainland China’s monetary easing cycle and hiking cycles in other major economies (such as the US and eurozone) have made RMB bond yields relatively less attractive in the last two years (figure 2.7). China’s two-year government bond yield, for example, is currently about 250 basis points below its US counterpart, and 80bp below its European counterpart.

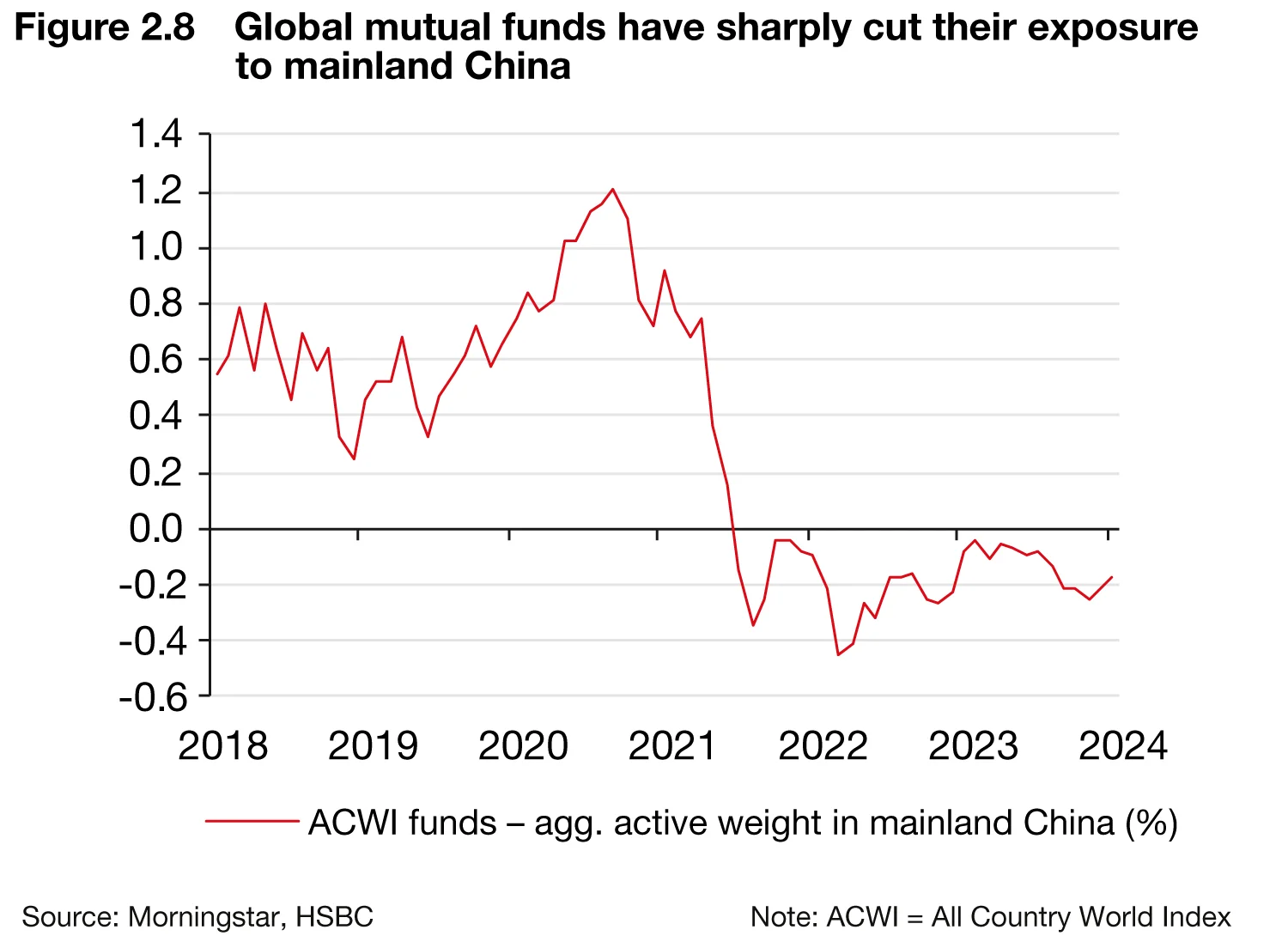

There could also be structural considerations, such as China’s ongoing debt restructuring in the property and local government sectors, and geopolitical tensions between the US and China. These issues may have affected the market’s view on China’s potential growth. HSBC equity strategists noted that global equity funds, which are dominated by US long-only funds, have been persistently reducing their exposure to China since 2020, shifting from an overweight to an absolute underweight now (figure 2.8).

However, a period of portfolio outflows by foreign investors does not necessarily mean the RMB’s prospects of being an international currency are bleak.

- First, it is not uncommon for international currencies such as USD and EUR to go through periods of outflows. For instance, during the European debt crisis, foreign investors sold €78 billion ($85 billion) worth of debt holdings in the eurozone in H2 2010, and another €173 billion in H2 2011. As for the USD, its share of allocated global reserves fell from 66% to 61% between 2006 and 2011 during the global financial crisis, as per the IMF’s Cofer survey.

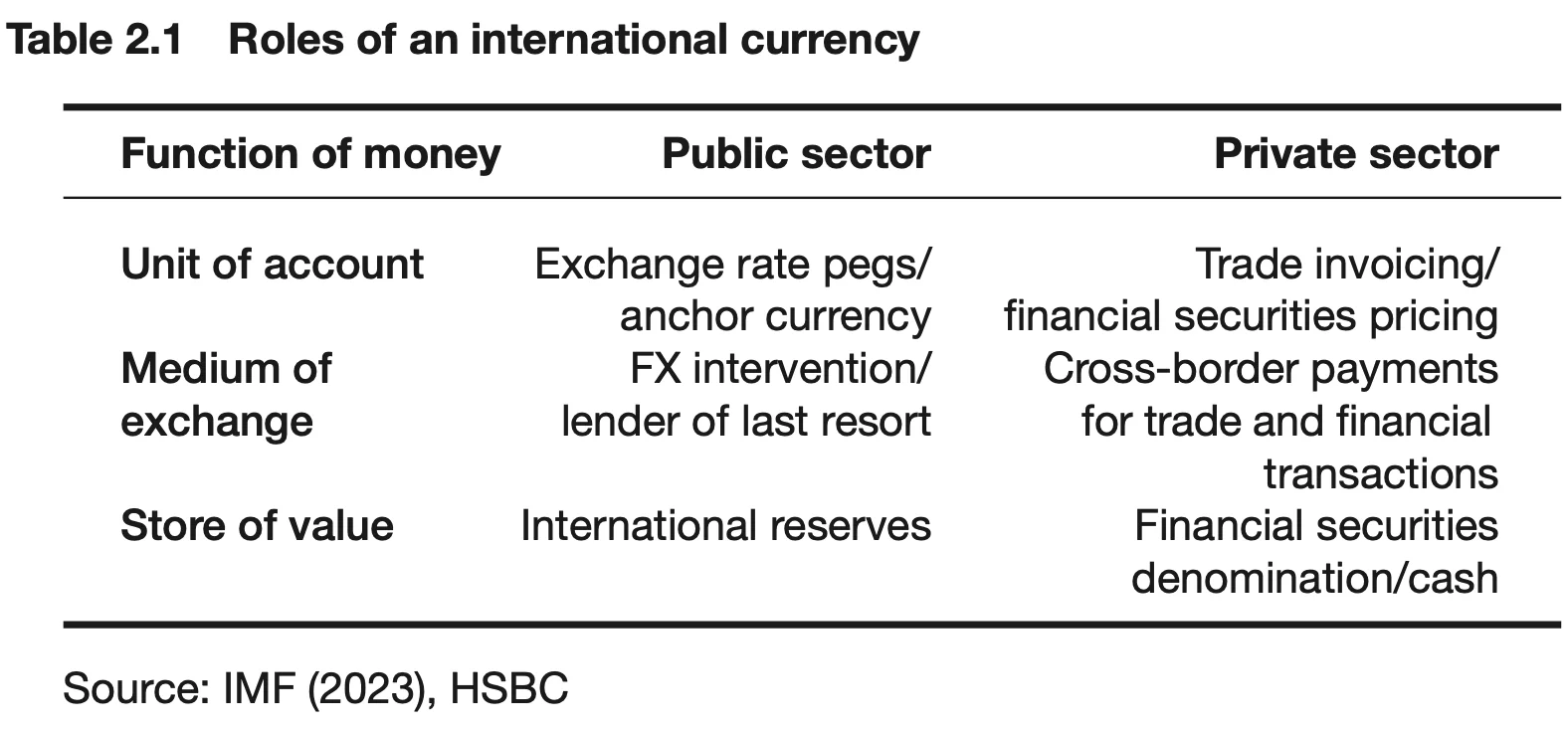

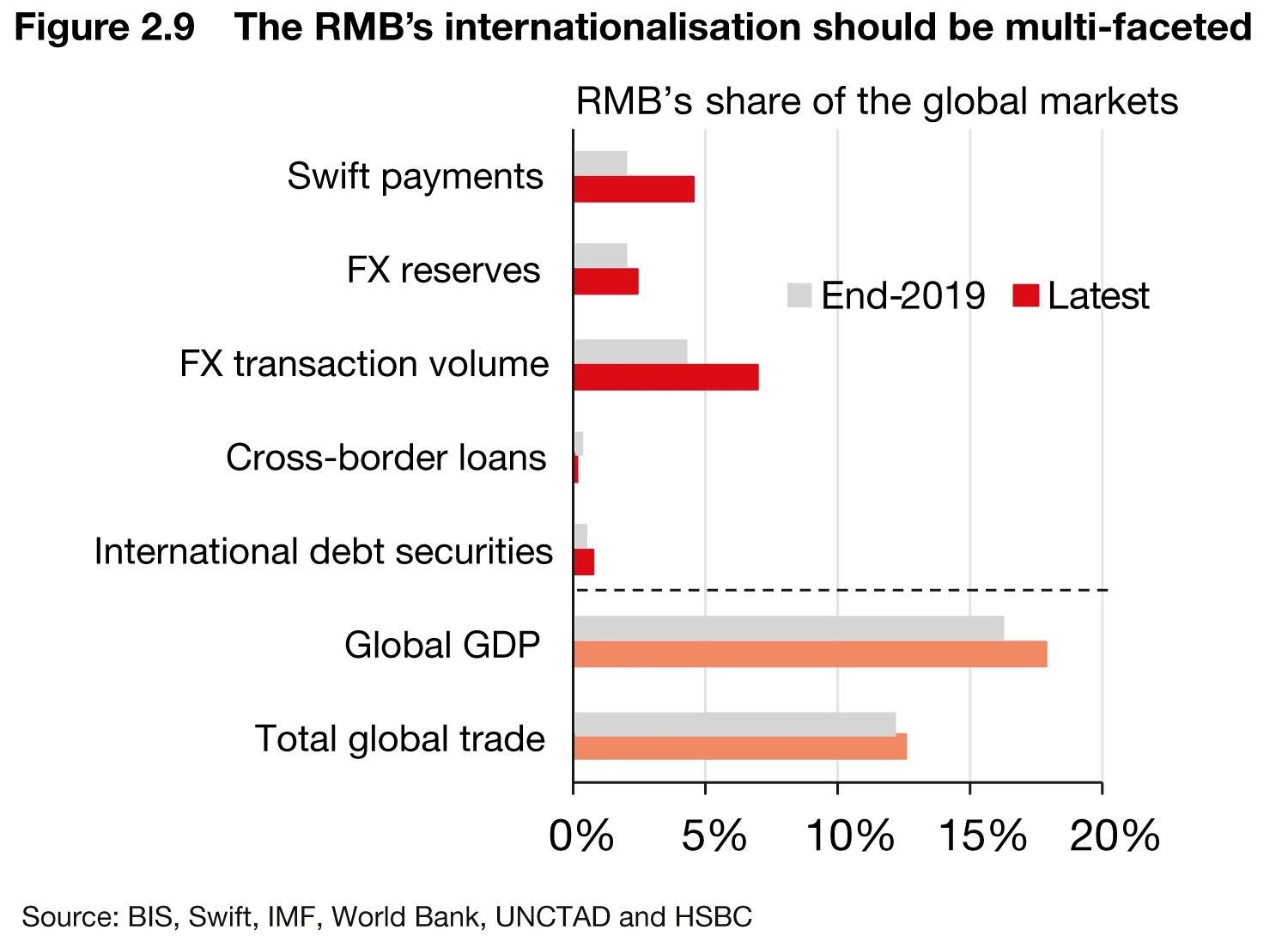

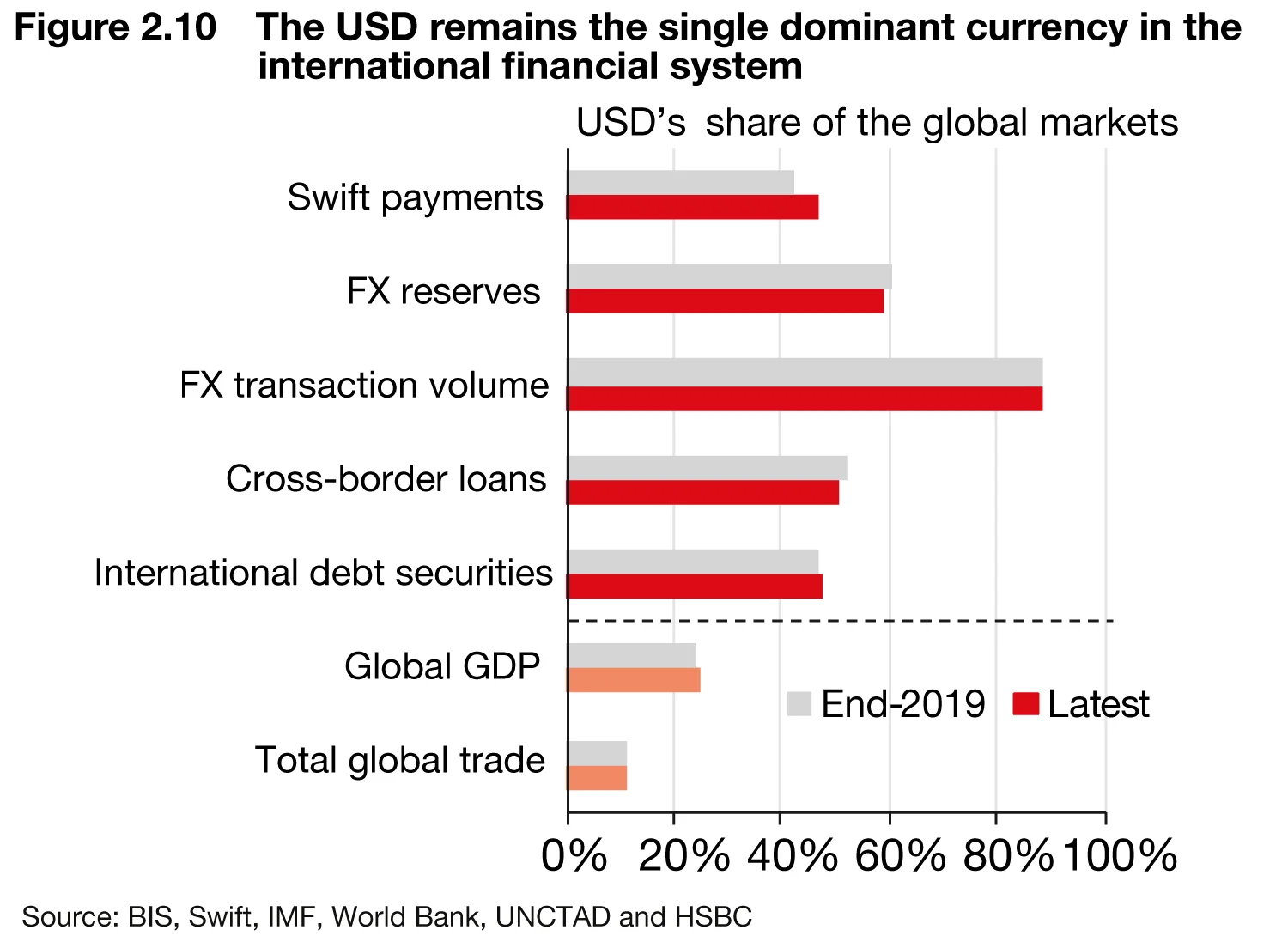

- Second, and more importantly, the RMB’s role as a store of value is only one of the multiple roles it should play as an international currency, as shown in table 2.1. In fact, the international use of the RMB has made notable progress in the other two functions – ie, as a unit of account and as a medium of exchange. In figures 2.9 and 2.10, we present some key indicators for the RMB and USD’s use in global markets. While the USD remains the dominant currency, the RMB has seen improvement in some key indicators, particularly in Swift global payments and FX transaction volumes. In the following sections, we will focus on two specific areas with meaningful progress – trade settlement and public financing.

Settling in RMB

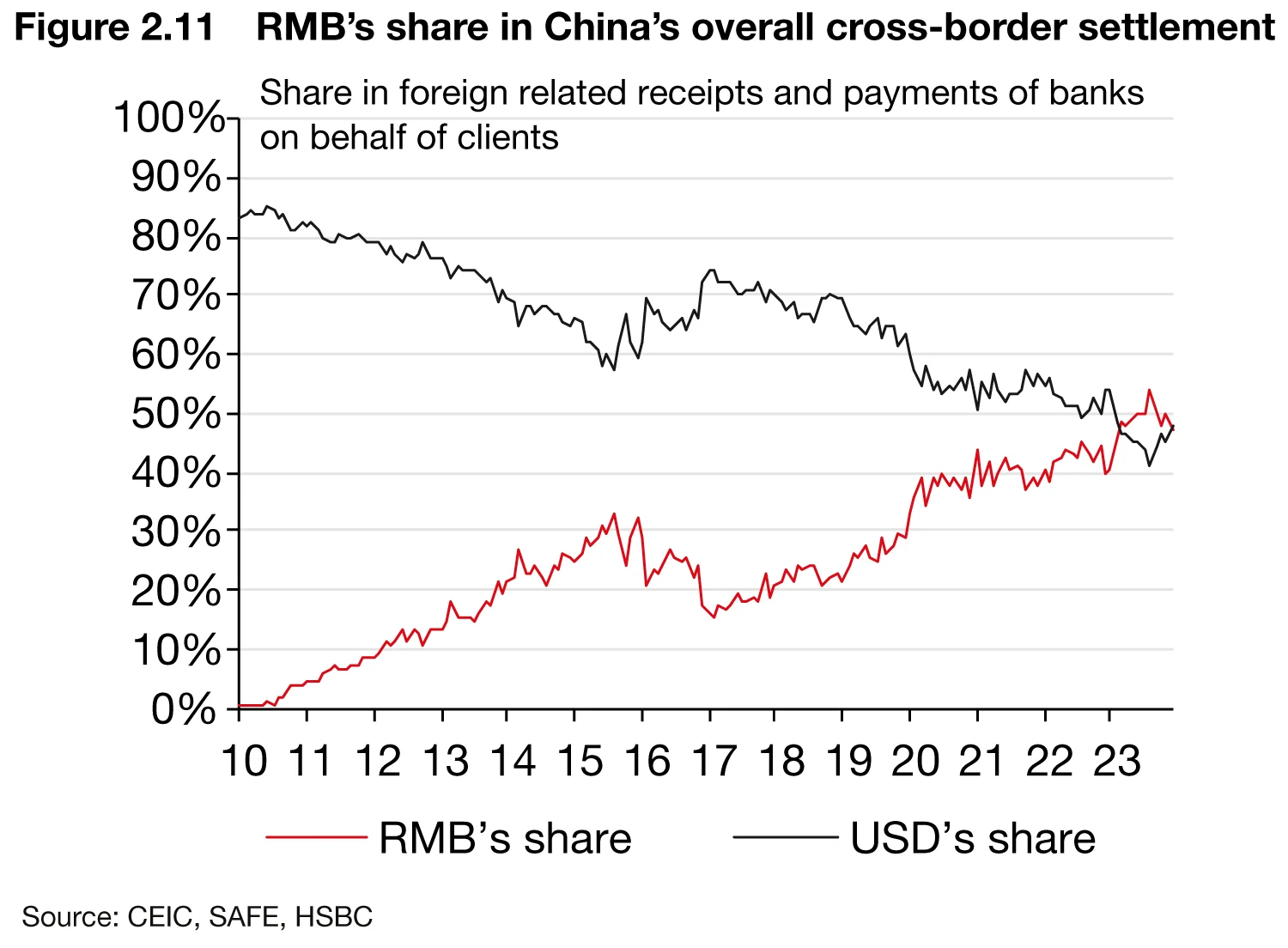

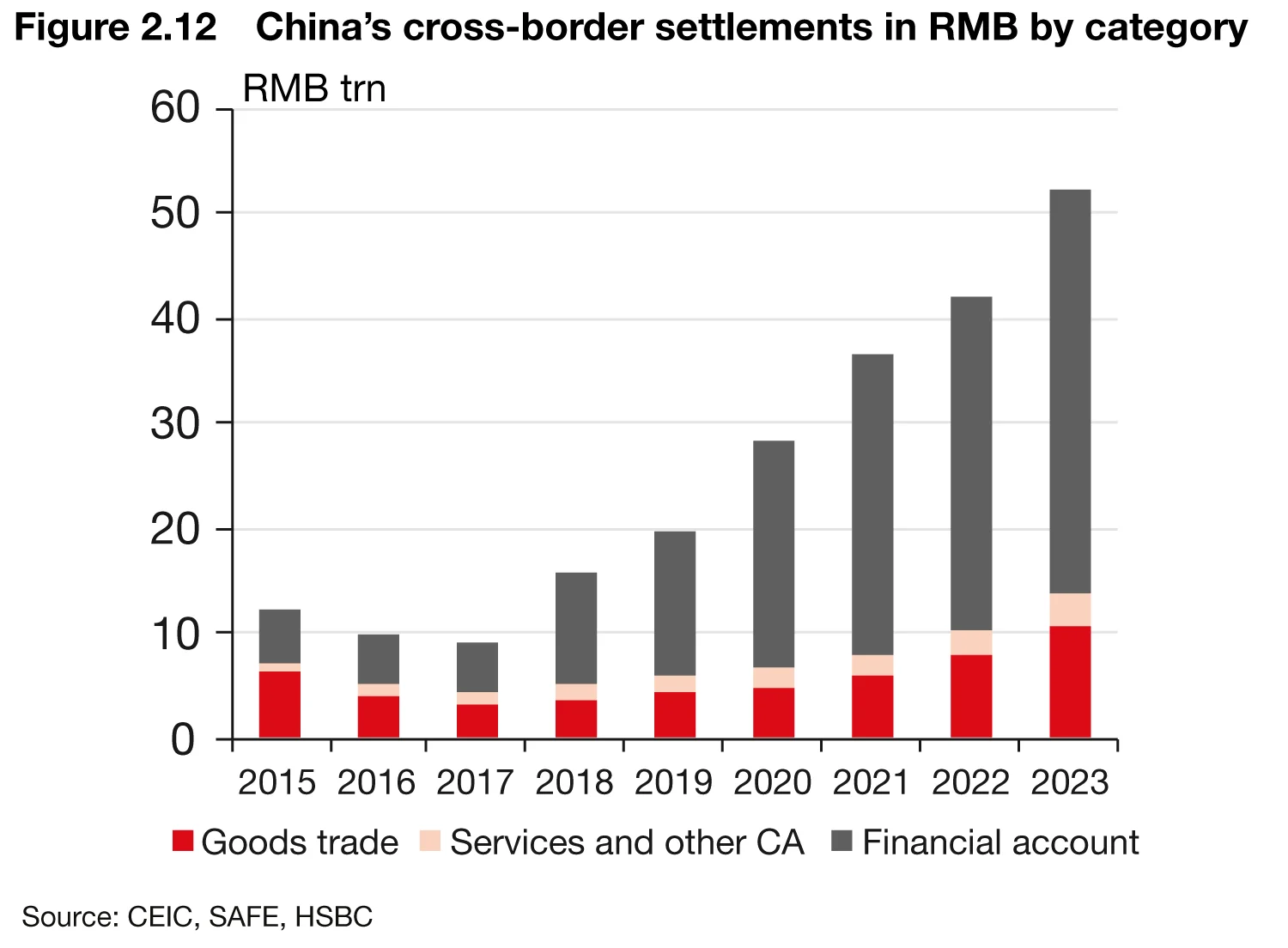

China reported that the RMB’s share in its overall cross-border settlement – including both the current and financial account – exceeded that of the USD in 2023 (figure 2.11). We think this is a slight exaggeration of the RMB’s progress as a settlement currency. This is because, in financial transactions (figure 2.12), most foreign investors had to convert from USD and other foreign currencies into CNH before investing through portfolio channels such as Stock Connect and Bond Connect.

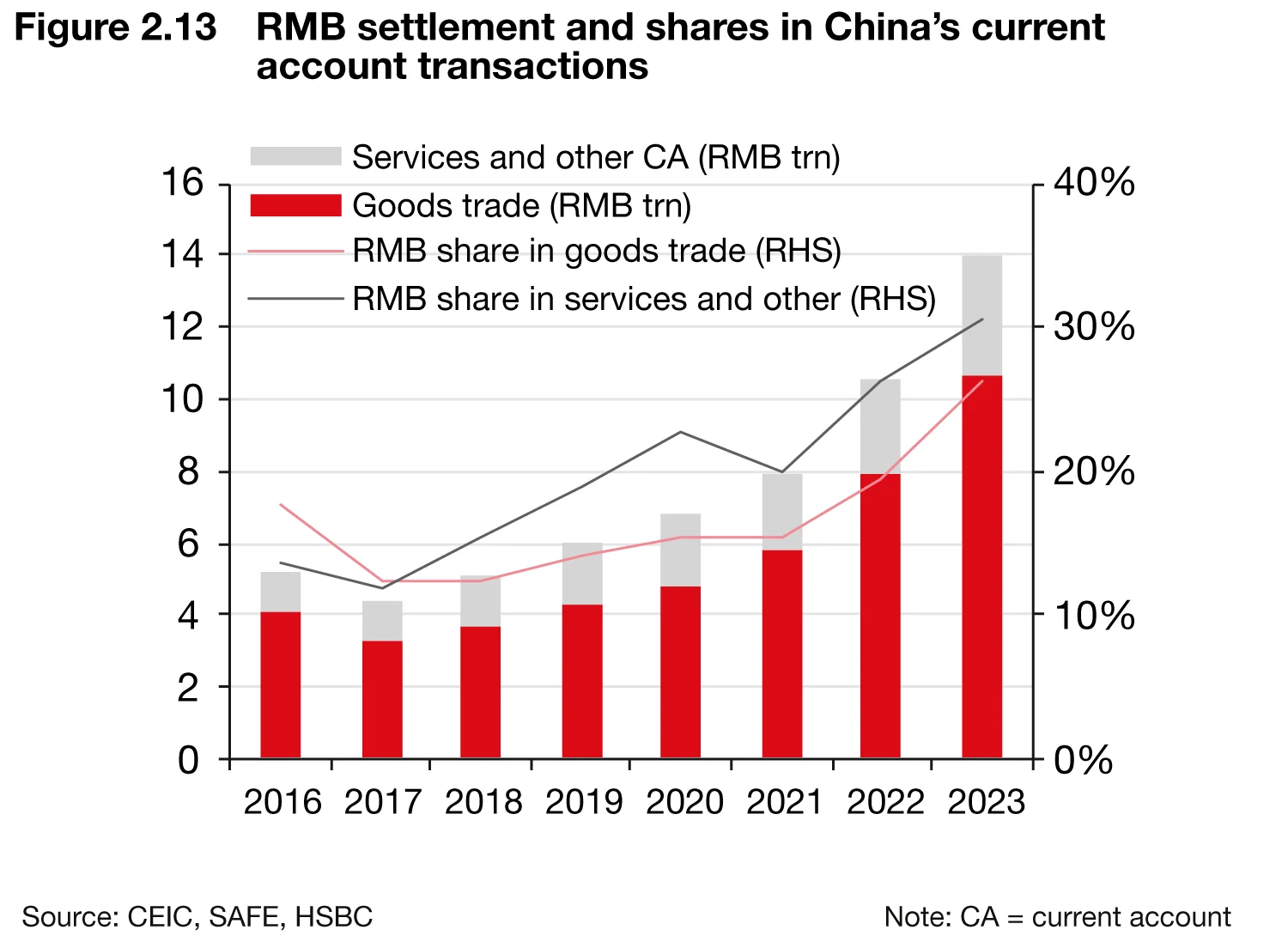

But a genuinely impressive improvement can be seen in the rise of the RMB as a trade settlement currency for goods trade (figure 2.13). RMB settlement accounted for 26% of China’s total goods trade in the first three quarters of 2023, improving materially from about 15% just prior to 2022. Its ratio in services trade and other current account transactions also rose from 20% to 29% during the same time.

This is not simply because of Russia settling more of its trade with China in the RMB. There has also been an increase in the RMB’s market share in global Swift payments (figure 2.14). The RMB’s market share improved to above 4% at end-2023, after being stagnant at around 2–3% for years. As stated above, the RMB has also replaced JPY as the fourth most active currency for global payments as of end-2023.

It is well known that there is a great deal of inertia when it comes to currency settlement. It takes a long time for a challenger currency to replace the incumbent because of the existence of network externalities that give rise to lock-in effects. For example, despite the stagnation of the US share of global trade in recent years, the USD remains the dominant currency in global payments, with its share in the Swift system even rising from about 40% at end-2019 to 47% currently (figure 2.10).

What contributed to the RMB’s sudden progress in 2023? We see conscious policy efforts as a driving force. The government has a view that the financial sector’s primary purpose is to serve the real economy and promote high-quality development. For RMB internationalisation, this means that its fundamental goal is to facilitate cross-border trade and investment. PBoC officials, including governor Pan Gongsheng, have stressed that further increasing the use of RMB in cross-border trade will bring convenience for corporates, including avoiding costs of FX conversion through third-party currencies, reducing FX risks and improving financing reliability. The central bank thus sees the use of RMB in cross-border settlement as a key measure to further improve “dual circulation” (in which the domestic economic cycle plays a leading role, while the international cycle is an extension).

- In 2023, there was a series of policy efforts to push the use of RMB in mainland China’s bilateral trade settlement. In March 2023, mainland China and Brazil reached a deal to settle trade in their own currencies. There have been ongoing discussions with Saudi Arabia to potentially price oil and gas trade in RMB after Chinese president Xi Jinping made such a suggestion to Gulf leaders in December 2022 (Reuters, November 20, 2023). According to Reuters, the share of oil transactions in RMB (estimated by Shanghai crude futures’ share in global crude oil trading volume) is currently about 5% in 2023, falling shy of its oil imports’ share of about 22% in global markets.

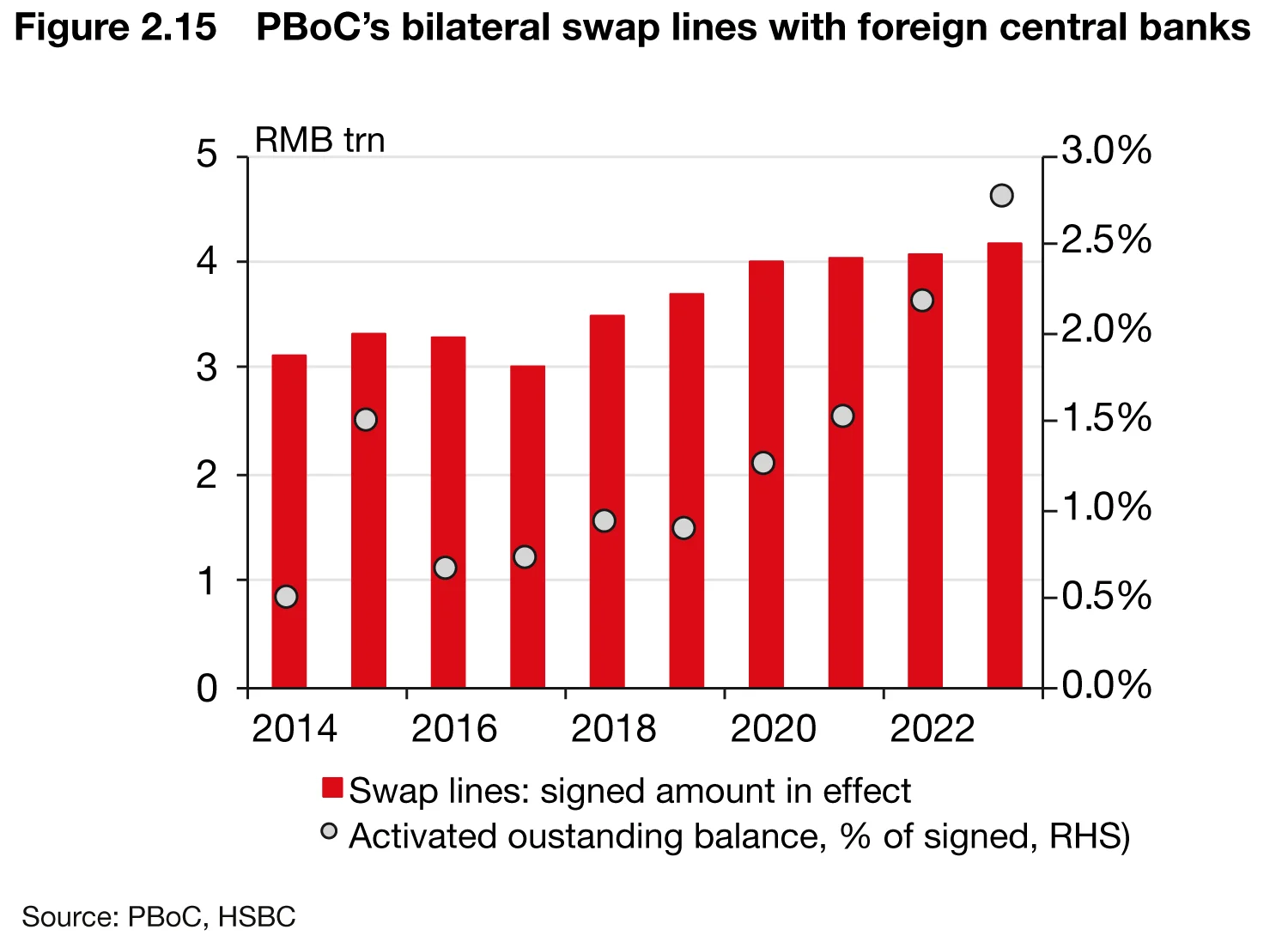

- The PBoC has further expanded its network of RMB swap lines with the monetary authorities of more economies, with total quota reaching 4.2 trillion yuan at end-2023. When the need for RMB liquidity arises for either trade and financial transactions, foreign central banks can activate the swap line and get RMB liquidity from the PBoC, using the equivalent amount of local currency as collateral. At the end of the swap, the foreign central bank will pay back the RMB at a pre-determined interest rate. Figure 2.15 suggests that, after staying idle for years, such swap lines have been more actively used by those in need of RMB liquidity in recent years (see next section).

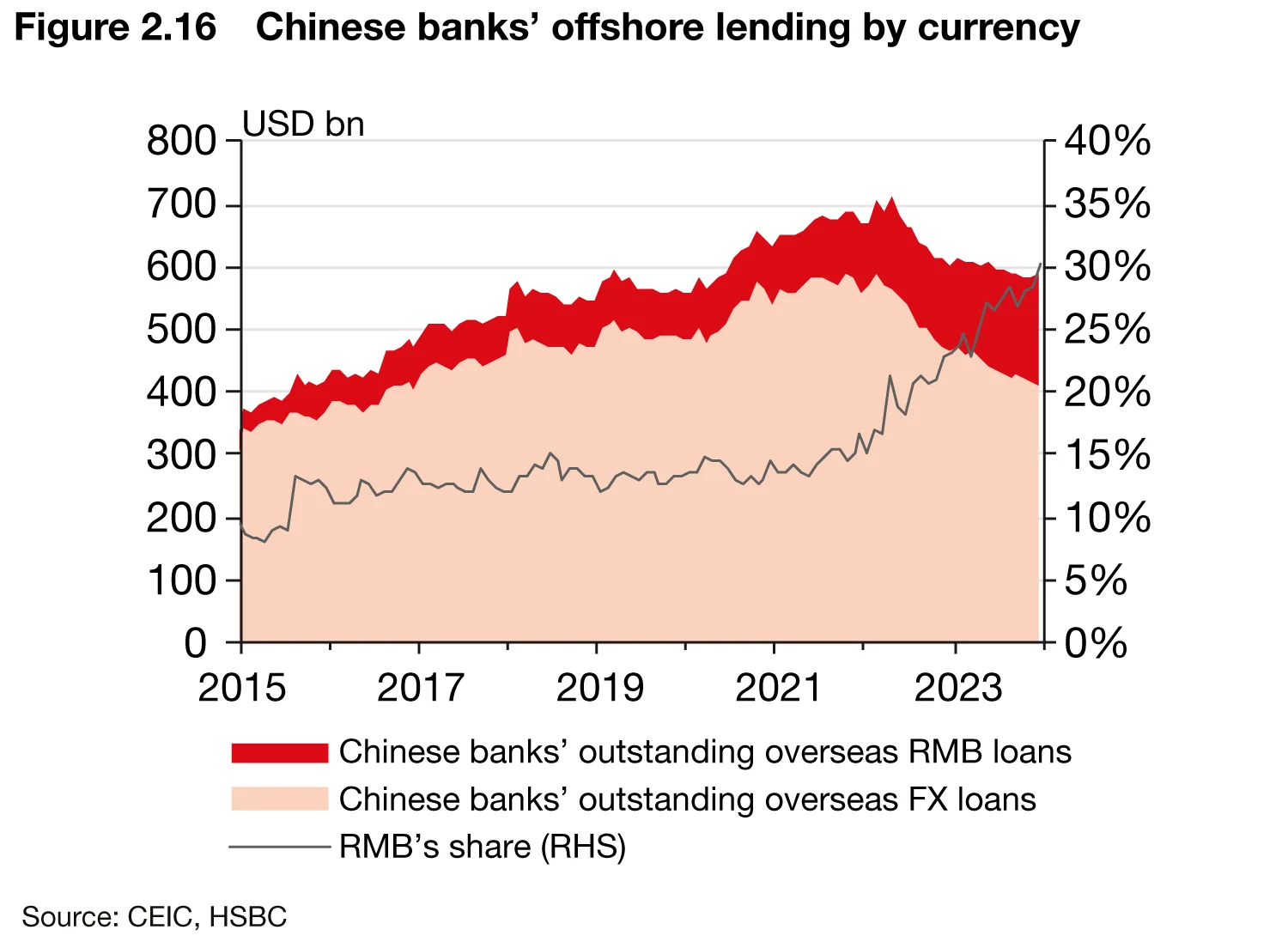

- Taking the cue from the authorities, financial institutions have also made notable efforts to expand access to RMB liquidity for China’s trade and investment partners. This is evident in a rapid rise in overseas RMB loans by Chinese banks since 2022 (figure 2.16). Back in 2021, only about 17% of their overseas loans were denominated in RMB, equivalent to about $111 billion. The size had grown to $191 billion in January 2024, and its share has risen quickly to 32%.

There have also been external developments that have helped. A rise in geopolitical risks has also fostered the use of RMB as an alternative currency for international payments, especially for trade. After the US and its allies froze Russia’s foreign exchange reserves and barred Russian banks from the Swift messaging system, many banks in Russia converted some FX assets into RMB assets, and replaced the New York-based Clearing House Interbank Payments System (Chips) with the RMB Cross-border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) set up by the PBoC (Yu, August 2023). A working paper by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development suggests that the share of Russia’s imports invoiced in RMB soared to 20% in 2022, from 3% in the previous year.

Room for improvement

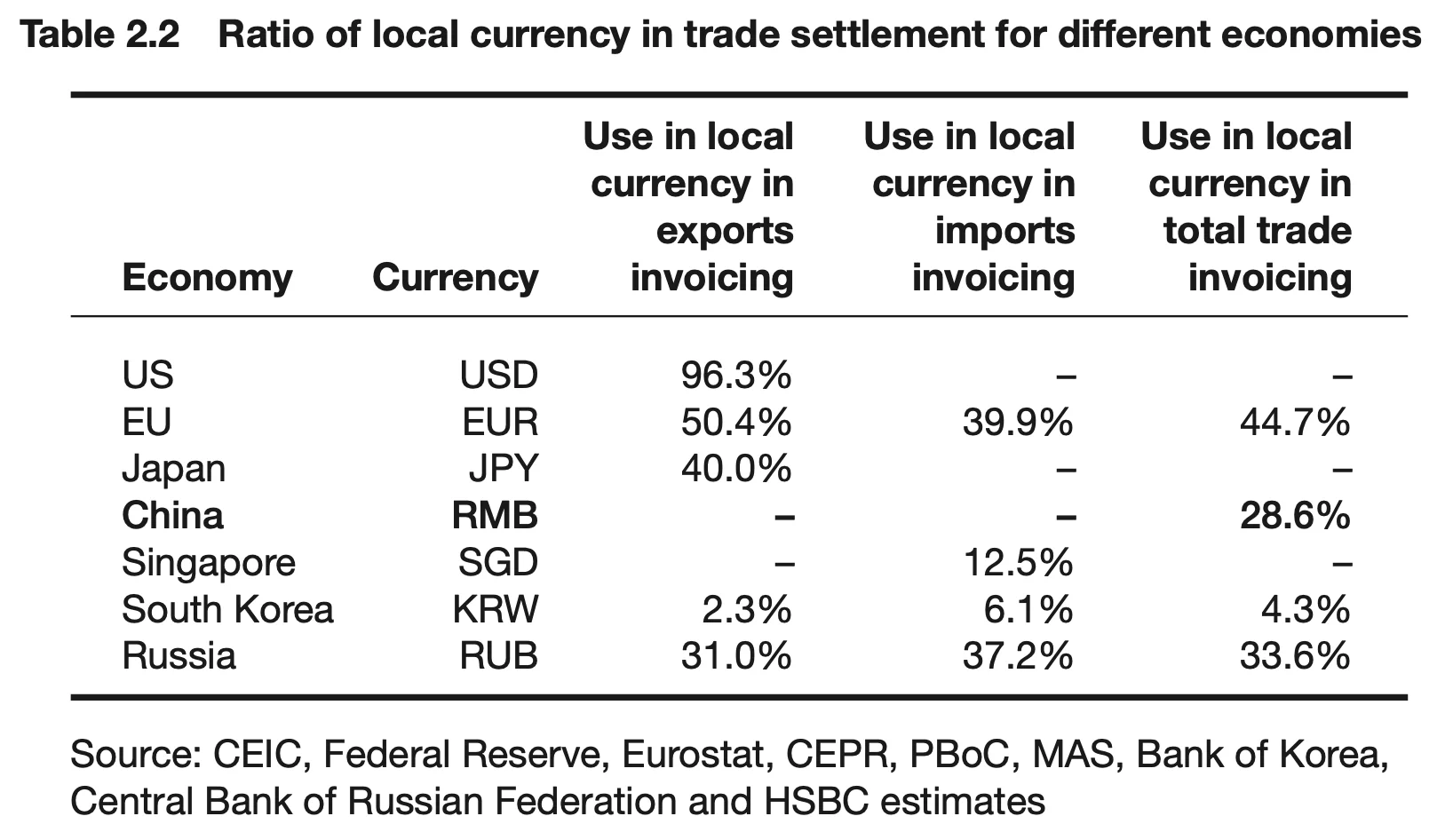

There is still room for further improvement. First, China’s RMB trade settlement is indeed higher than other Asian emerging markets such as KRW for South Korea, but it is still lagging that of major global economies (eurozone, UK, Japan), especially the US (over 90%). In table 2.2, we summarise the latest data on local currency usage in each country’s own trade settlement. Second, a country’s high use of local currency in trade settlement does not naturally make it a more acceptable currency internationally. For example, Russia’s trade settlement in RUB has almost doubled from 18% of total trade in January 2022 to 34% at end-2023 as a consequence of sanctions linked to its invasion of Ukraine. But the global role of RUB is unlikely to have grown in the meantime.

Ultimately, what makes the USD impressive is not its use in the US’s own cross-border transactions, but its use as a vehicle currency in third-party transactions unrelated to the US (ie, pure offshore transactions). But for the RMB, there is no evidence of the rise of its usage in such third-party transactions. For instance, South Korea and Singapore – two economies with close trade and investment links to mainland China – still only invoice about 1–2% of their global trade in RMB, while the lion’s share (84% of South Korea’s total trade and 73% of Singapore imports) is still settled in USD. A monthly RMB tracker published by Swift suggests that offshore RMB payments excluding mainland China rose more notably in 2023, but this is mainly attributed to payments in Hong Kong, which were likely still more or less correlated to cross-border trade or investment with mainland China.

Therefore, in our view, a higher level of internationalisation has to come from the wider use of the RMB by foreign investors in international trade and financial transactions unrelated to China, as well as the long-term holding of RMB and RMB assets. The following factors can lay the groundwork for further development:

- China’s sheer size in international trade remains its biggest advantage in further internationalising the RMB. Moreover, in recent years, China has pushed through multiple trade agreements, including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). In total, mainland China has signed off 21 free-trade agreements (FTAs), which involve 28 economies (including Hong Kong and Macao). Another 10 FTAs are currently under negotiation, and eight more are under consideration, according to the Ministry of Commerce. In the latest 2024 Government work report, China has also reiterated that it will continue to work towards joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). All these developments should provide opportunities to grow tighter trade links with neighbouring countries. Empirical studies suggest that this is important.

- For example, strong trade links were a key determinant of the stronger role of the EUR for invoicing international trade. Between 1999 – the year of the EUR’s creation – and 2019, the share of the EUR increased by more than 20 percentage points on average in invoicing by countries neighbouring the eurozone at the expense of the USD. Recent European Central Bank (ECB) staff research (June 2023) suggests that the increase in trade links of those countries with the euro can explain on average almost 40% of the rise in the share of exports invoiced in euro during that period.

- A working paper published by the IMF (March 2023) suggests that countries that have closer trade linkages with mainland China tend to settle a larger portion of trade in RMB, based on Swift data.

- The development of infrastructure that ensures offshore RMB liquidity and stability should also continue, including bilateral currency swaps established between the PBoC and foreign central banks, and the designation of offshore RMB clearing banks, as they have been proved to be effective in encouraging more RMB payments. Various empirical studies suggest that countries where the PBoC has set up RMB swap lines or offshore clearing banks tend to have a higher growth of RMB payments with mainland China (Eichengreen, 2022). They create expectations that RMB balances will be liquid and can be borrowed, bought and sold, when the offshore RMB market is relatively shallow (like now).

- Policy-makers can develop other incentives to offset switching costs way from the USD and other currencies. To that end, the prospective use of e-CNY in cross-border payments may provide significant potential for efficiency gains. The PBoC is one of the four founding central banks for the Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) Project mBridge, which experiments with a multiple-central bank digital currency (multi-CBDC) common platform for cross-border payments and FX transactions. The latest report from the project suggests that the platform would allow cross-border payments to be “immediate, cheap and universally accessible with final settlement”.

- Future development of mainland China’s CIPS may also continue to attract a lot of attention, as it is regarded as having the potential to provide direct communication lines linking financial organisations settling cross-border transactions in RMB, and thus to operate independently of Swift. Latest data suggests that a daily average of 17,700 messages via CIPS in 2022 is dwarfed by nearly 50 million a day for Swift. But some observers envisage CIPS transactions increasing rapidly, especially if more countries look for alternatives in the case of more US sanctions or trade tariffs (Yu, 2023).

Lender of last resort

The RMB as a financing currency has been another area where progress has been made. According to the BIS’s statistics, the global market share of RMB-denominated loans and bonds remains small, at below 1%, and its growth has been slow. But there have been some improvements worth highlighting.

First, alongside trade settlement, the RMB has naturally gained a little market share in global trade finance – 5% in late 2023, from less than 2% two years ago.

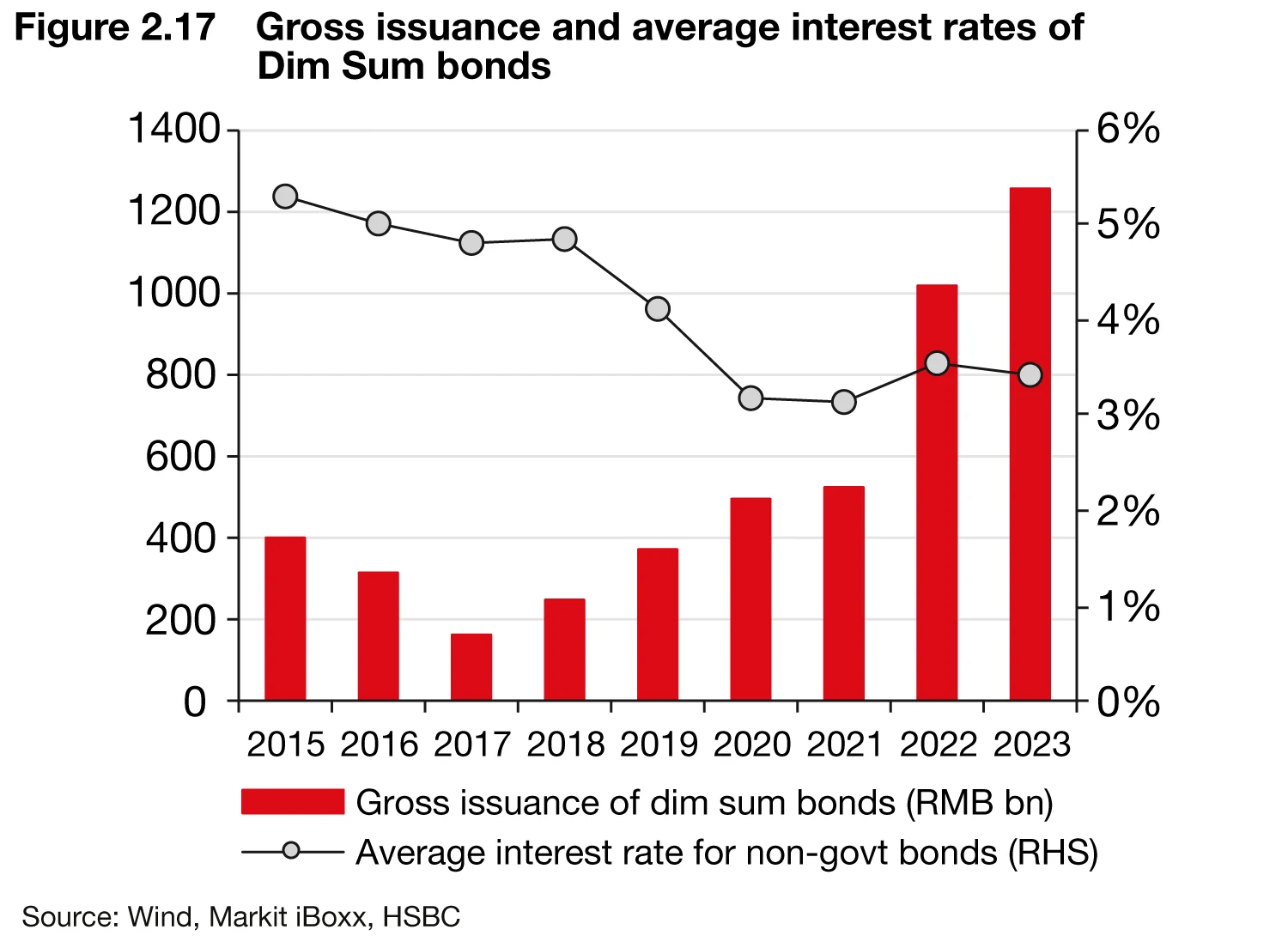

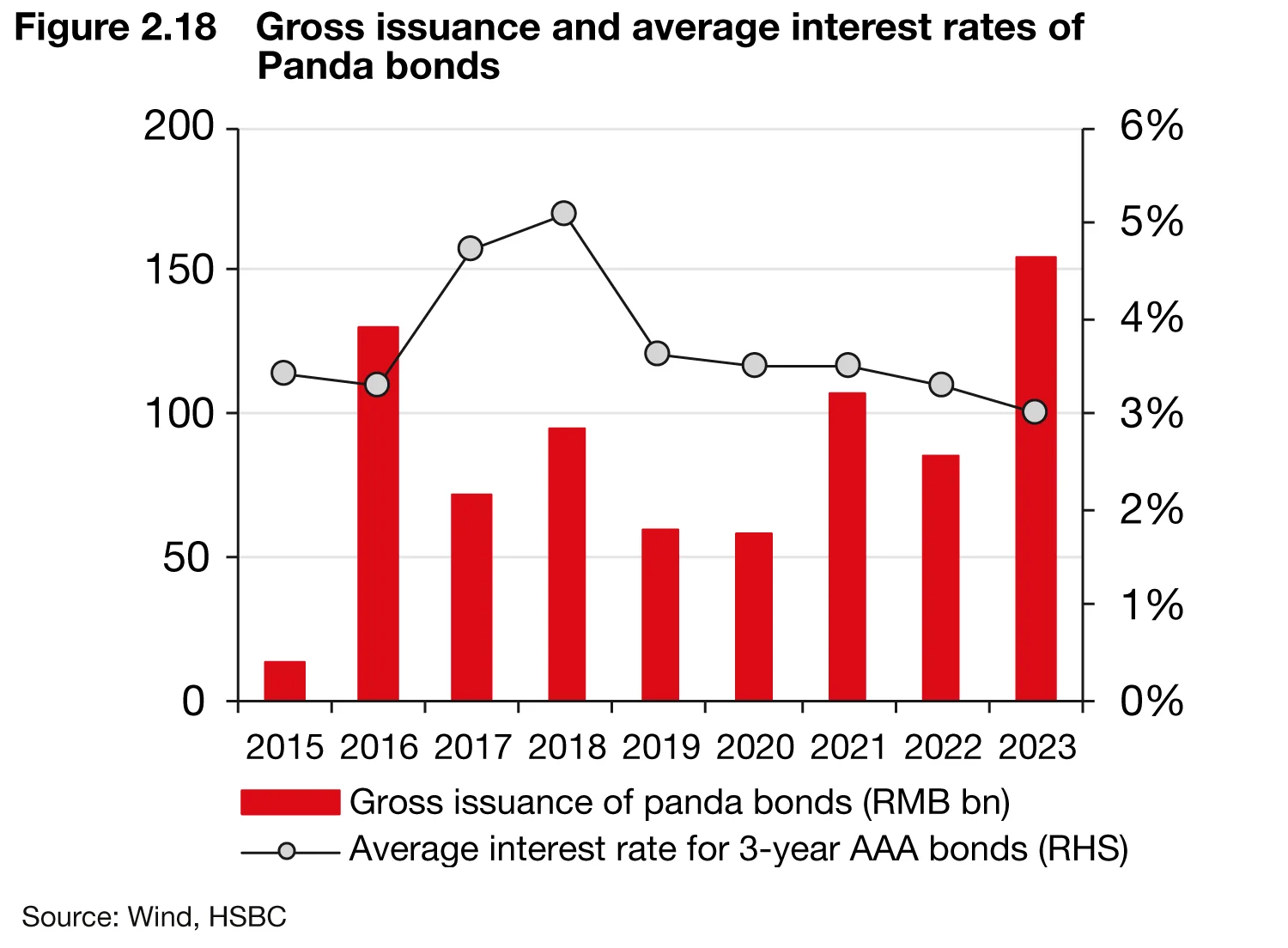

Second, the issuance of both Dim Sum bonds and Panda bonds has picked up pace in the recent years. Gross issuance of Dim Sum bonds reached 1 trillion yuan for the first time in 2022 and further rose to 1.26 trillion yuan in 2023 (figure 2.17). Gross issuance of Panda bonds nearly doubled in 2023 to 154 billion yuan (figure 2.18). The rising issuance of RMB-denominated bonds by foreign entities or in offshore markets may reflect the currency’s relatively lower borrowing costs compared with major currencies (eg, USD and EUR) after the US Federal Reserve and ECB started aggressively hiking rates. In addition, in December 2022, regulators clarified that the funding proceeds raised through Panda bonds could be repatriated overseas, providing much-needed flexibility to foreign issuers.

Third, recent studies suggest that the RMB has also made progress as a public financing currency (which is not included in the BIS data mentioned above), against the backdrop of Beijing becoming an international lender of last resort.

China’s overseas lending to low- and middle-income countries (LICs and MICs) has grown alongside the development of BRI projects around the world. This is now hovering around $80 billion a year, according to AidData, more sizeable than the US development finance of about $60 billion each year to LICs and MICs.

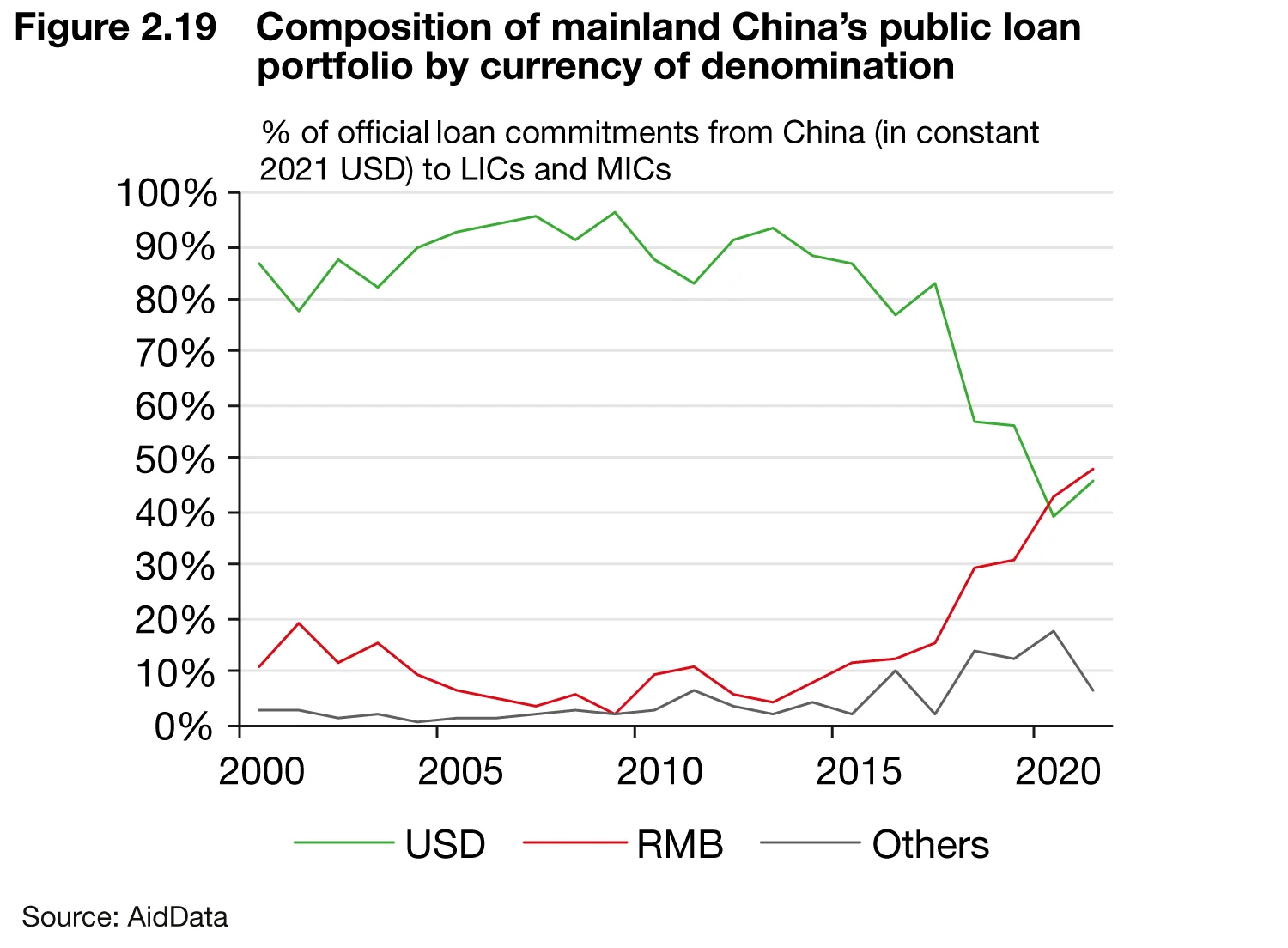

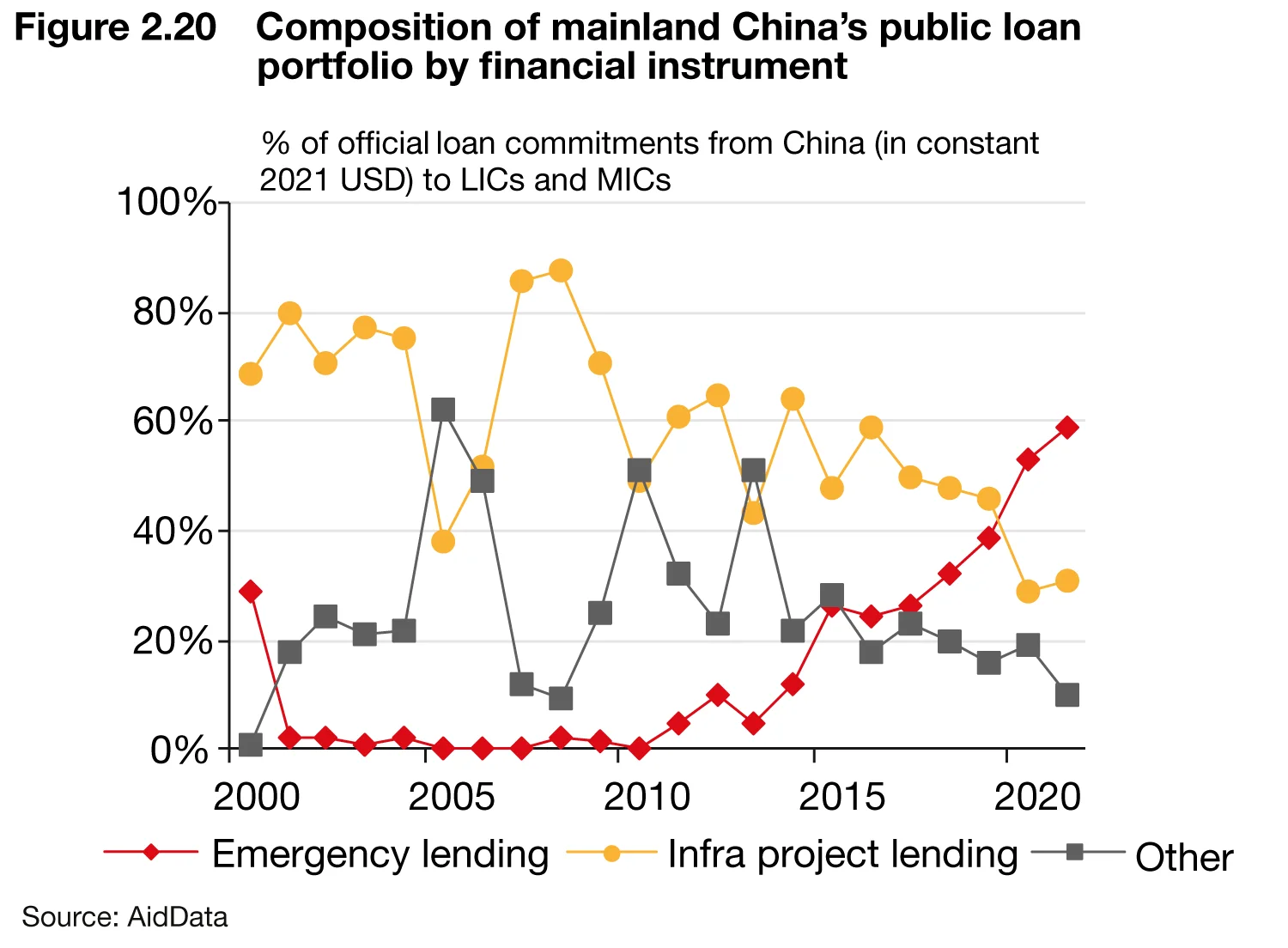

Prior to the launch of the BRI in 2013, China’s overseas lending portfolio was dominated by USD-denominated lending for infrastructure projects. But from 2014 onwards, in recognition of a growing percentage of this infrastructure debt having reached principal repayment dates, Beijing has fundamentally altered the composition of its overseas lending portfolio:

- First, China has ramped up RMB-denominated lending, and the USD’s importance in its overseas lending portfolio steadily declined. AidData estimates that the share of RMB-denominated loans in new lending commitments from China has soared from 6% in 2013 to 50% in 2021, while the USD-denominated loans’ share decreased from 93% to 44% over the same period (figure 2.19).

- Second, China’s focus has shifted from infrastructure lending to emergency rescue lending. When the BRI was initially launched, Beijing provided most of its overseas lending for big-ticket infrastructure projects such as high-speed railways and telecommunication networks. But in recent years, China extended an increasing ratio of its lending as emergency liquidity support for LICs and MICs. By 2021, more than half of China’s overseas lending consisted of emergency rescue lending (figure 2.20).

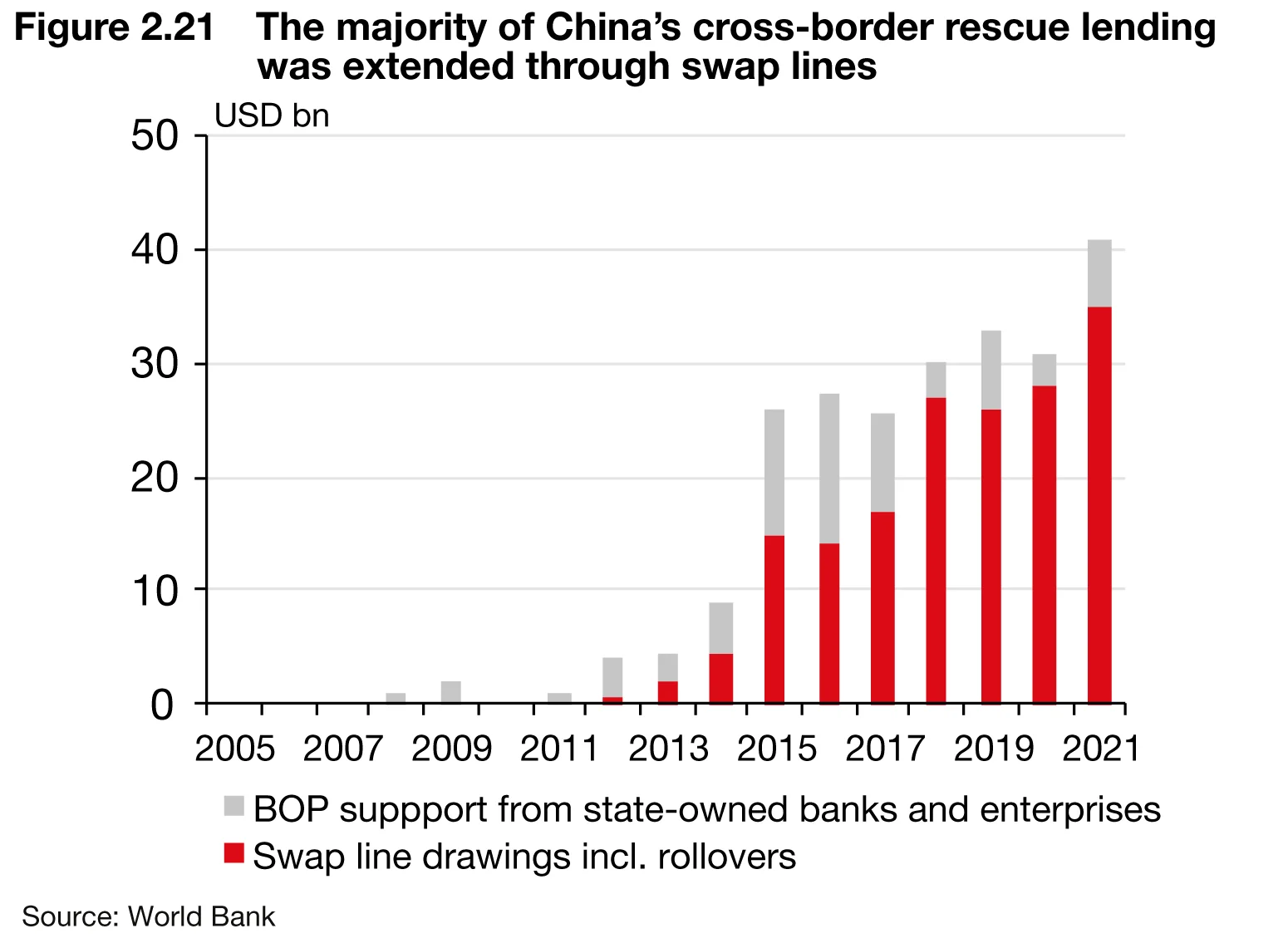

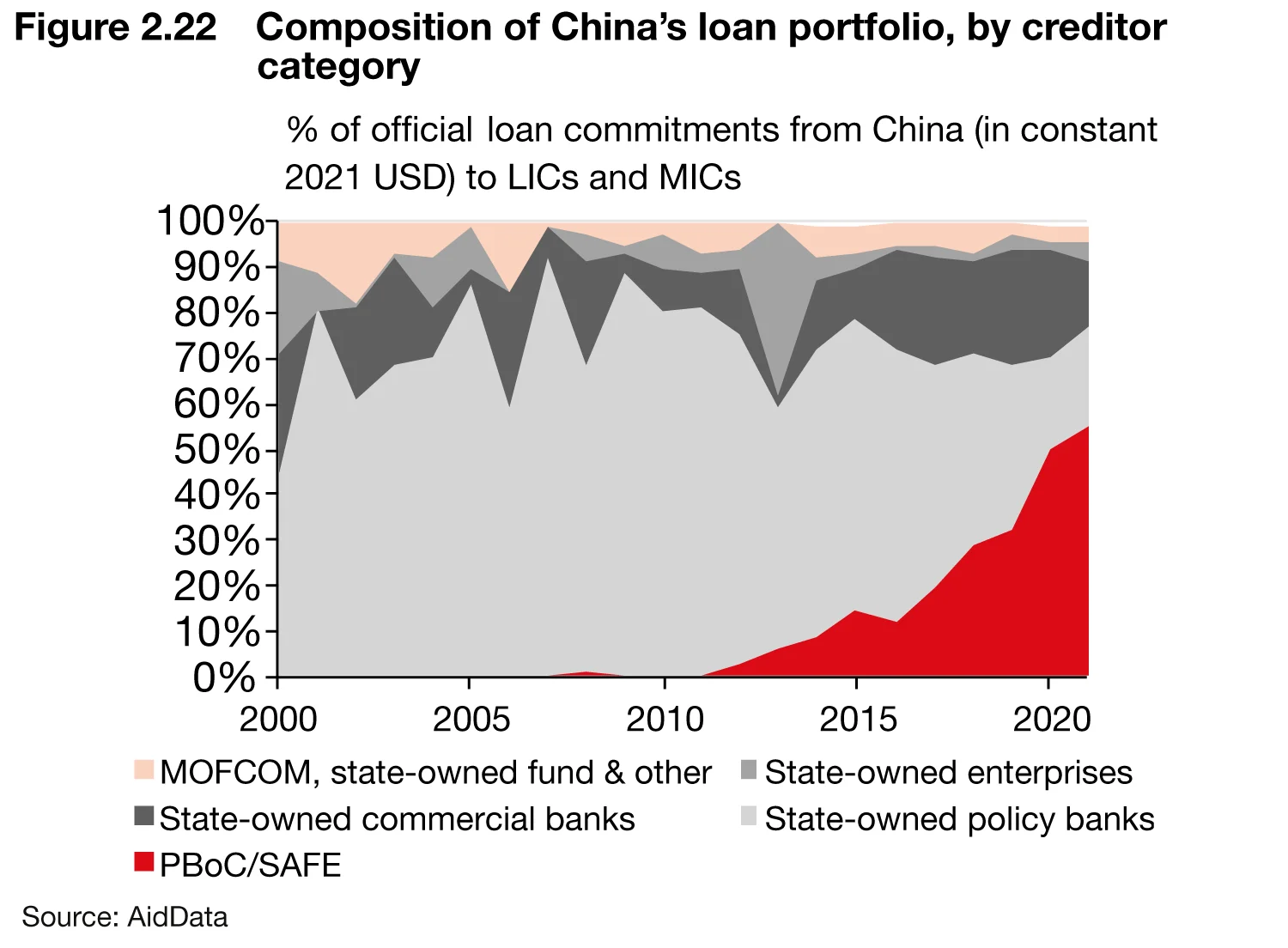

- The PBoC’s RMB swap lines have become an increasingly important channel to provide such RMB-denominated emergency liquidity support. A working report by the World Bank suggests that of the $240 billion worth of China’s cross-border rescue lending that it had investigated between 2000 and 2021, 70% was extended through the swap line drawings (figure 2.21). The PBoC has also grown into the most important financier of China’s cross-border rescue lending operations, accounting for 54% such lending commitments in 2021 (figure 2.22).1

In short, China is cutting back on USD-denominated infrastructure project lending, while ramping up RMB-denominated emergency rescue lending to financially distressed borrowers. China’s new role as the lender of last resort serves its strategic goal to ensure that recipient countries can continue servicing their outstanding infrastructure project debts with China. For instance, Laos has an exceptionally high level of public debt exposure to China (at least 43% of GDP, according to the World Bank’s estimates). When the Laotian authorities urgently sought debt relief from their Chinese creditors in 2020, Bank of Laos made the first drawdown of its bilateral swap lines with the PBoC in June 2020, when its gross reserves stood at only 1.5 months of import cover, and rating agencies warned of a high default probability. Fitch Ratings then said the proceeds from its swap line drawing “helped to boost FX reserves”.

China has also issued RMB-denominated emergency loans to a number of borrowers when they were facing difficulty repaying their USD-denominated loans, as a way to ensure that its largest borrowers with USD-denominated debts to Chinese creditors do not exhaust their USD reserve holdings. In a recent example, the PBoC helped Argentina make three large debt service payments to the IMF in June, July and October 2023. As IMF loans can be repaid with multiple currencies (including USD, EUR, RMB, JPY, GBP and SDR), Argentina’s central bank repaid its debt to IMF with RMB drawings under a swap line worth about 9.3 billion yuan, which allowed it to preserve USD reserve holdings.

In addition to the purpose of helping overseas borrowers avoid default, China’s role as the lender of last resort is also encouraging more use of the RMB as a settlement currency, and may eventually help expand the uses of RMB as a reserve or investment currency, as well. In fact, China’s willingness to serve as an international lender of last resort today is reminiscent of a similar role that the US played during the 1930s and after World War II, when it provided USD-denominated emergency rescue loans to borrowers with large outstanding USD-denominated debts to US banks and exporters. These activities laid the groundwork for the USD to eventually become a dominant currency for reserve holdings and international financial transactions.

Conclusion

RMB internationalisation is multi-faceted, and remains a key part of the currency being a reserve currency. Between 2015 and 2021, various reforms were made to facilitate foreigners’ investment in onshore RMB assets. Recently, the policy focus has shifted towards promoting the RMB in bilateral trade settlement and in public-sector loans to developing economies.

Ultimately, all these growing linkages – via investment, trade and financing – between China and the rest of the world in China’s own currency suggest that there is an important role for RMB to play in global FX reserves. Apart from asset diversification benefits, reserve managers may also want to take into consideration how the RMB can be increasingly used in settling and financing real economic activities. The USD similarly started out as a trade and financing currency in pre-war times. The RMB’s linkages to the global monetary system will continue to grow over time, only to aid its reserve status.

Some foreign experts – notably Barry Eichengreen – now hold the view that the RMB can grow to become a complement to the USD in the international monetary system, through its trade and financing links with the ‘Global South’. With the development of China’s trade and investment links with emerging markets (such as those through the BRI), together with the development of infrastructure facilitating the international use of the RMB, foreigners will be further encouraged to accumulate and hold RMB reserves. These experts have backed away from the historical assumption that capital account liberalisation by China or full convertibility of the RMB is a prerequisite for RMB internationalisation.

What could be the implications for the FX market? Besides further policy efforts to be made to enhance mainland China’s trade links and access to RMB liquidity, a degree of RMB stability may also be helpful to make the currency more widely accepted. In particular, Eichengreen suggests that the RMB’s stable and predictable convertibility into the USD is important. In this regard, he sees a similarity with the USD in terms of the role that gold played for the currency under the Bretton Woods system, and thus believes the Chinese authorities’ maintenance of USD reserves at least partly remedies the incomplete convertibility of the RMB.

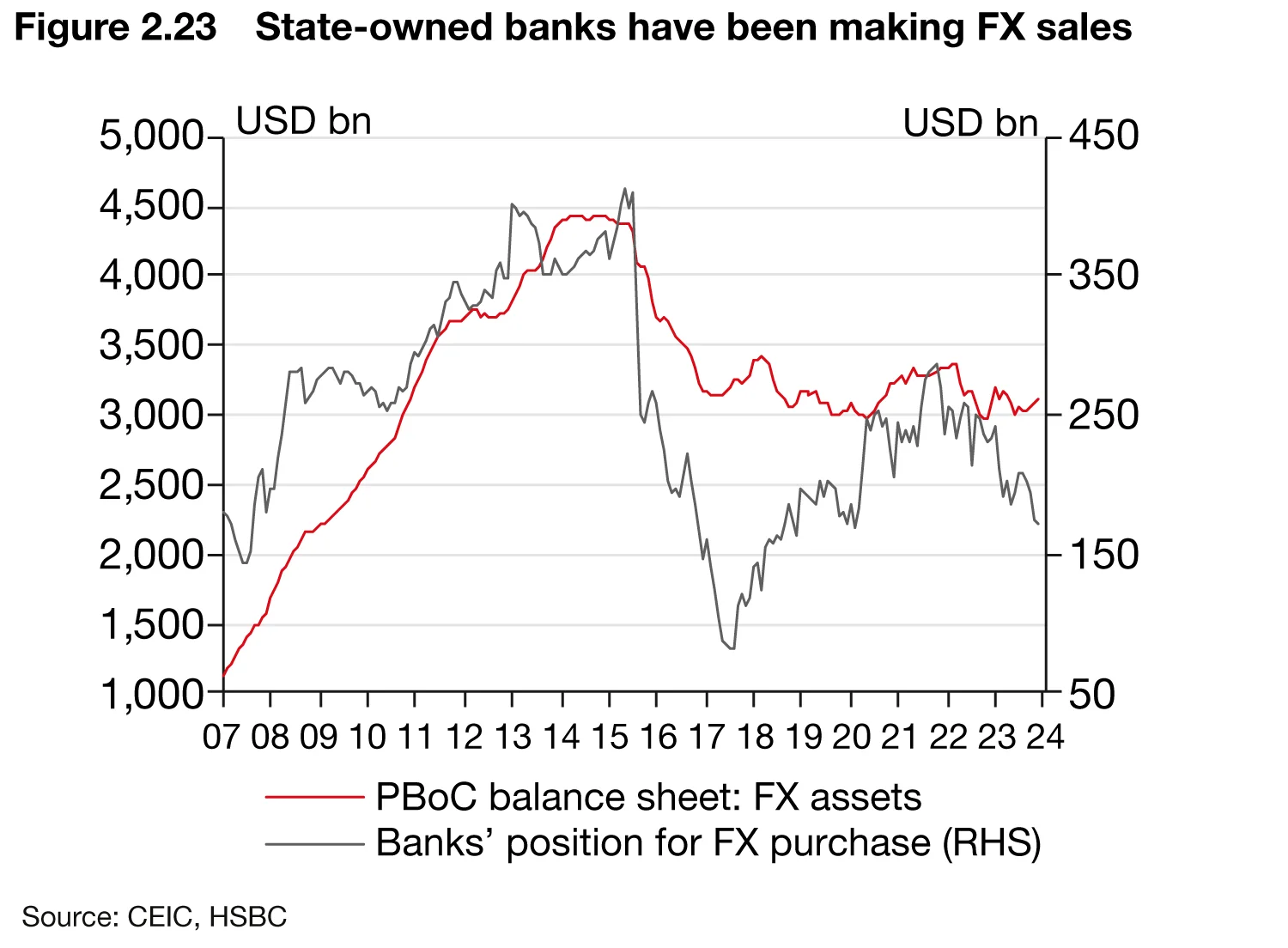

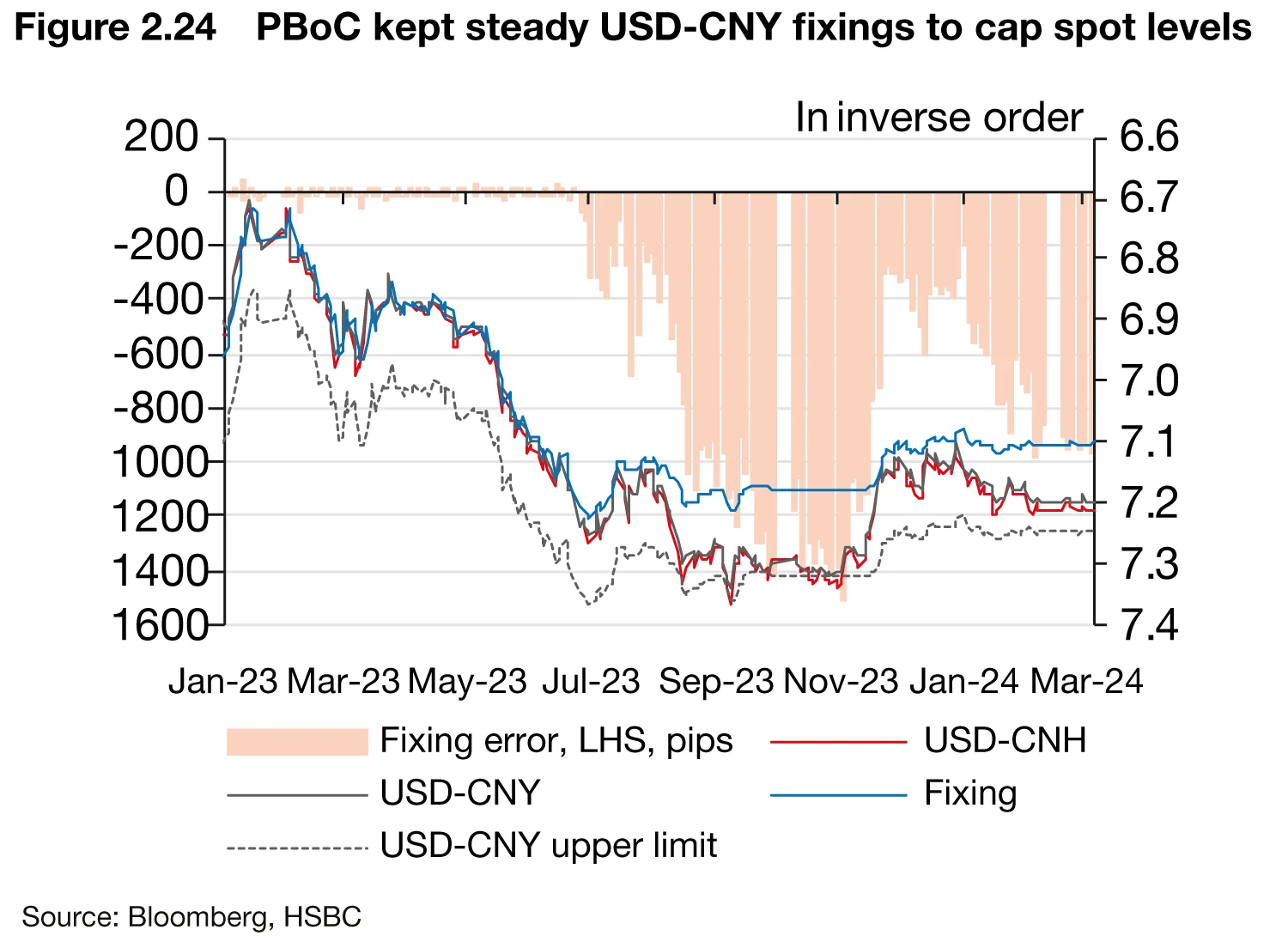

This view provides a new perspective for us to understand the PBoC’s strong desire for stability in USD-RMB in the periods of DXY strength. In our view, stability can foster strength but also feed into the longer-term goal of promoting RMB internationalisation. Recall that back in 2015–16, the PBoC used $833 billion worth of FX assets (or about one-quarter of the total amount) on its balance sheet for intervention. But in 2022–23, the PBoC has been much more restrained with such substantial direct intervention. Instead, we find that domestic banks in China appear to have made more FX sales, judging by the decline in banks’ ‘other sources of foreign currency’ (a series we use to proxy for the discontinued ‘banks’ position for FX purchase’).

In 2024, the RMB is still facing headwinds from its weak fundamentals – a wide yield disadvantage against the US and low confidence in the Chinese economy. While these two factors may start to improve when the Fed kicks off its easing cycle or Beijing rolls out stronger policies to improve its growth outlook, we caution against premature optimism as concerns over geopolitical tensions may become more influential as the US election approaches.

Our base case is that the PBoC will continue to hold a defensive stance to maintain a degree of stability in USD-RMB. We will also be on the lookout for potential new regulations or ‘window guidance’ that could boost FX supply onshore. For example, on January 23, 2024, Bloomberg reported that the mainland Chinese authorities were considering asking state-owned enterprises to deploy their offshore funds to buy stocks – which could prop up the currency and the onshore equity market simultaneously.

Note

1. The World Bank suggests that the PBoC’s swap lines are mostly drawn in situations of financial and macroeconomic distress by low- and middle-income BRI countries with significant debt outstanding to Chinese banks. Out of 17 countries that have made PBoC swap line drawings by 2023, only four did so in normal times, with no apparent signs of distress. Examples of such rescue lending through swap lines include Argentina (2014–2021), Mongolia (2012–2021), Suriname (2015–2021), and Sri Lanka (2021), which drew on their RMB swap lines right before and/or after sovereign defaults on their external creditors. Other important users include Pakistan (2013–2021), Egypt (2016-2021) and Turkey (2021), which made large drawdowns during protracted balance of payments crises, as demonstrated by their rapidly deteriorating currencies in the face of dwindling foreign exchange reserves. Another group, including Russia (in 2015 and 2016) and Ukraine (in 2015), activated their swap lines in the face of sanctions and deep geopolitical crises.

References

AidData, Belt and Road reboot: Beijing’s bid to de-risk its global infrastructure initiative, November 2023.

Bank for International Settlements, Project mBridge: experimenting with a multi-CBDC platform for cross-border payments, October 2023.

Eichengreen, Barry, Macaire, Camille, Mehl, Arnaud, Monnet, Eric, and Alain Naef, Is capital account convertibility required for the renminbi to acquire reserve currency status?, Banque de France Working Paper, November 2022.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Exorbitant privilege and economic sanctions, EBRD Working Paper, September 2023.

European Central Bank, How is a leading international currency replaced by another? Old versus new evidence, June 2023.

International Monetary Fund, Currency usage for cross-border payments, March 2023.

International Monetary Fund, Renminbi usage in cross-border payments: regional patterns and the role of swaps lines and offshore clearing banks, IMF Working Paper, March 2023.

World Bank, China as an international lender of last resort, Policy Research Working Paper, April 2023.

Yu, Yongding, Reflections on the RMB internationalization as the international monetary system enters a new historical stage, CF40 Research, August 2023.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com