The NBP’s gold purchases – a view from the risk management trenches

Paulina Domagalska, Juliusz Jabłecki, Maciej Pomykała and Navdeep Singh

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2024 survey results

RMB – internationalisation is not over

Managing the tides: the dynamic history and future challenges of Korea’s foreign reserve diversification

Interview: Jonas Stulz

Reserve management at the National Bank of Slovakia

The NBP’s gold purchases – a view from the risk management trenches

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

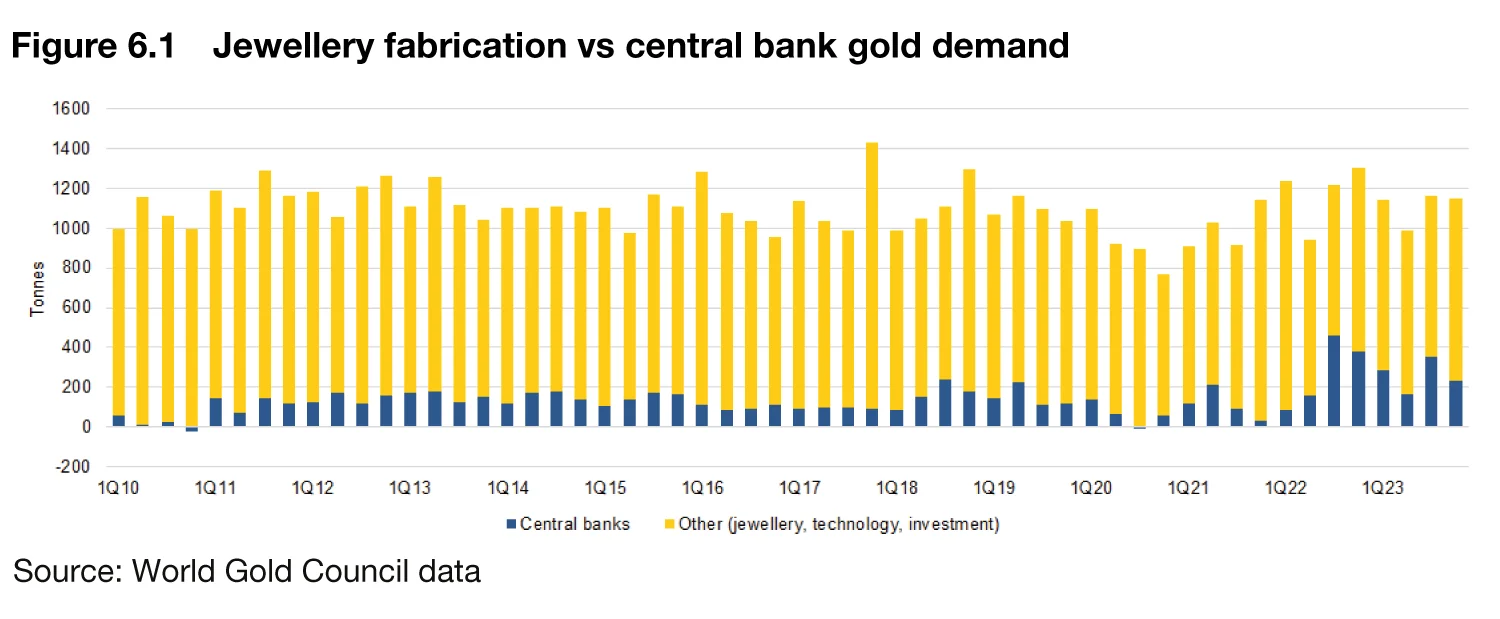

Although central bank demand for gold still represents a relatively minor share of the total global demand for gold (dominated for years by jewellery fabrication), central banks’ share has recently been on the rise, with reserve managers’ purchases roughly doubling in size relative to the average levels observed in the more peaceful decade of 2010–2020 (figure 6.1).1

According to the World Gold Council’s Central bank gold survey, the performance of the precious metal during times of crisis and its role as a long-term store of value are among the key reasons for central banks to hold gold. Similarly, according to a recent NMG survey, allocating to the precious metal is a favoured means of protecting against global inflation trends as well as – at least for some managers – diversifying away from the US dollar, whose appeal is seen as waning on account of high debt levels and – more recently – weaponisation of reserves.

In view of all of this, it is probably fair to conclude that gold is not just yet another ‘asset class’, having served as a pillar of the world’s monetary system centuries before the term was even coined. That legacy probably also goes a long way towards explaining why many still see it as an ultimate anchor of value and stability, contrasting its virtues with the drawbacks of fiat currencies (ie, paper money issued by government-backed central banks).2

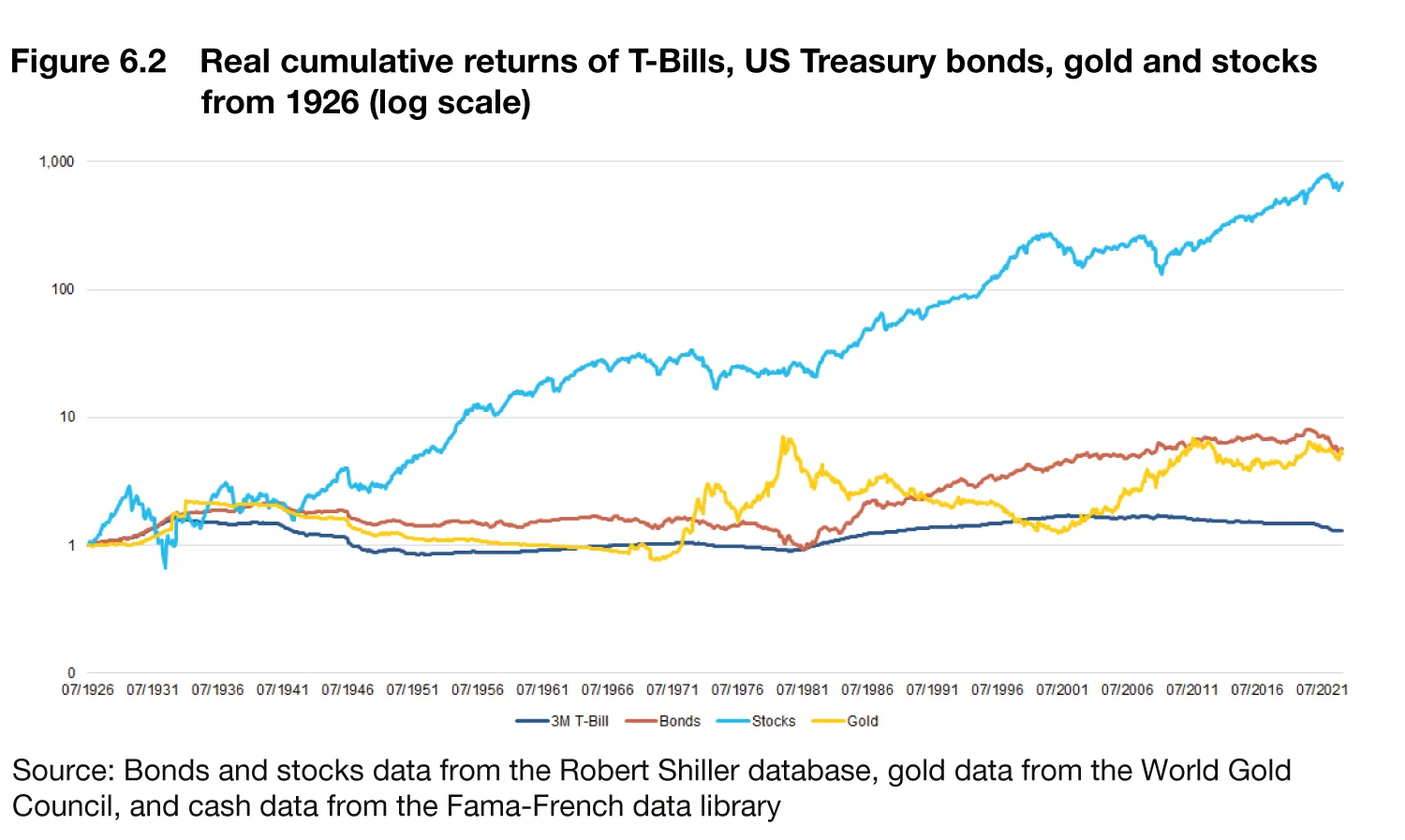

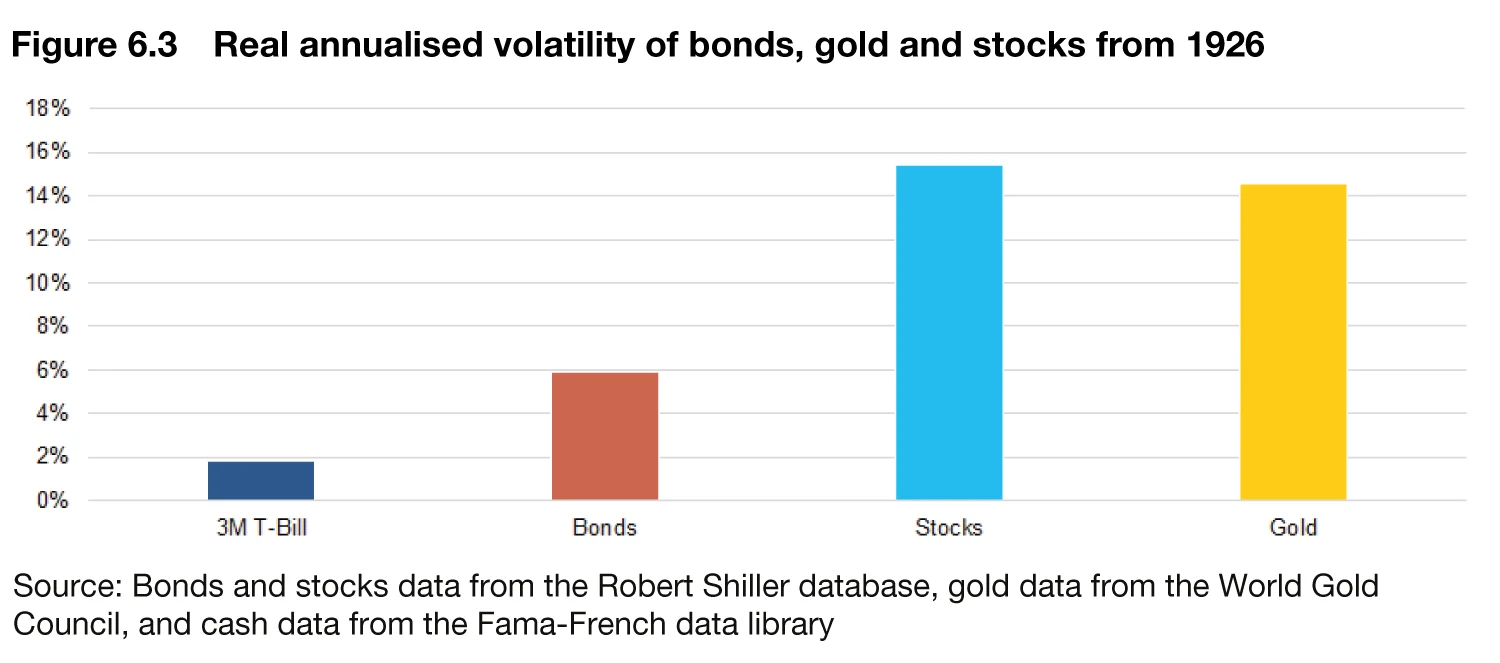

However, empirical evidence from a long sample going back over 100 years points to potential problems with this popular interpretation (figure 6.2). Indeed, since 1926, the annualised real return on gold was just 2.8% – compared with 8.0% on US equities, 2.0% on 10-year US Treasury bonds and 2.1% on commodities. The large discrepancy in returns relative to stocks is partly due to the fact that gold does not accumulate income, while the reinvestment of dividends, for example, contributes almost two-thirds of the compound long-term return earned by holding stocks. At the same time, gold is much more volatile than either T-Bills or bonds, with the annualised standard deviation of monthly returns roughly on par with that of equities (figure 6.3).

Thus, gold appears to deliver lower real risk-adjusted returns than traditional financial assets, making it at first glance a less than obvious choice for long-term institutional investors such as central banks. How should we then reconcile these tendencies with its apparent popularity among reserve managers? Is there perhaps more to gold than suggested by the evidence reported in figures 6.2 and 6.3? We address these questions below, drawing inspiration from the thinking and analyses that informed the development of the National Bank of Poland’s (NBP) gold strategy and its purchases of roughly 256 tons over the past six years.

The NBP’s FX reserves

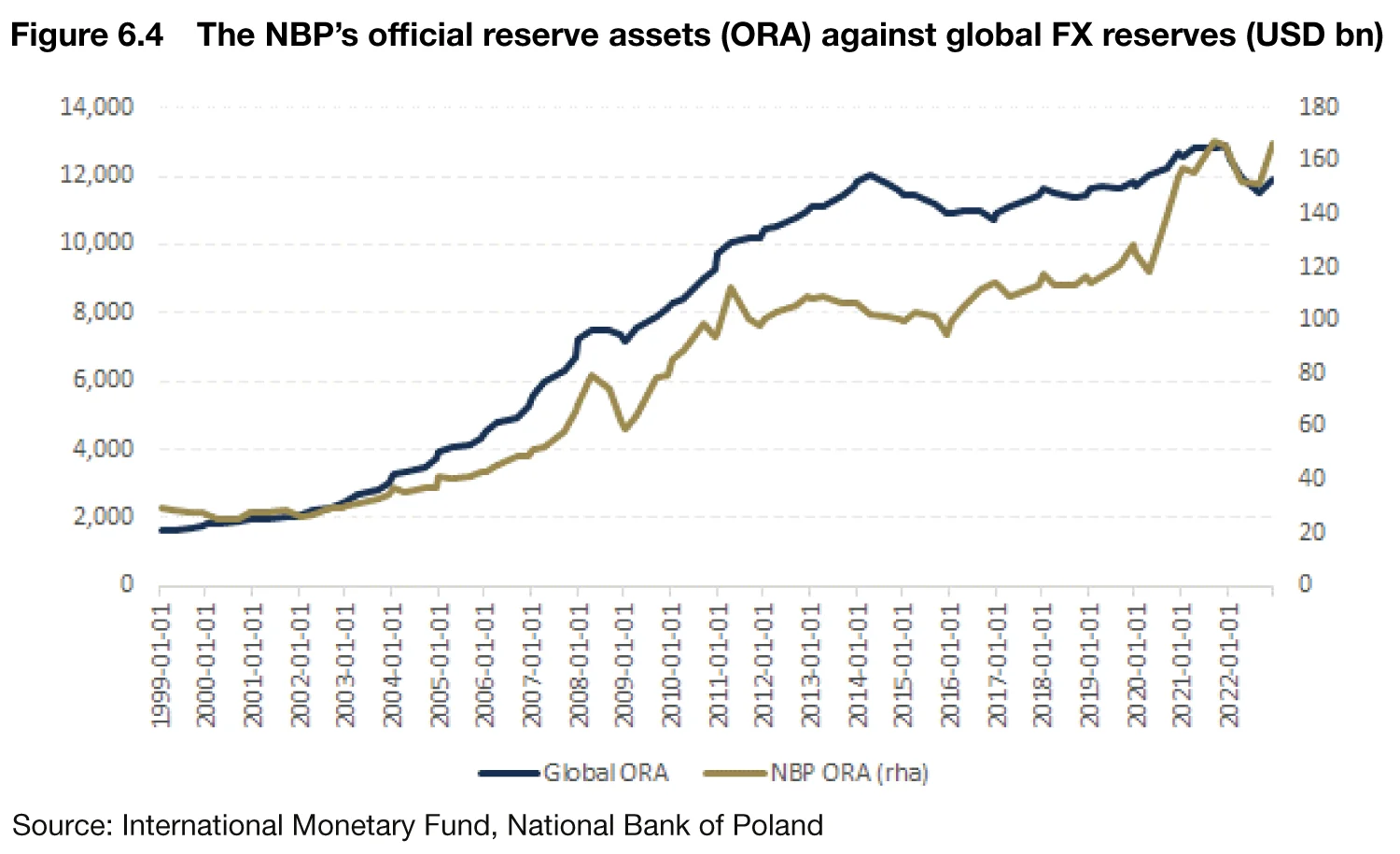

The NBP manages reserves totalling $189 billion as of end-2023, up from just $20 billion in 2000, and almost double the level reached in 2010. While our portfolio has grown roughly in line with the size of global official reserves (figure 6.4), the main factor driving reserve accumulation has been the purchase and off-market conversion of European Union funds.

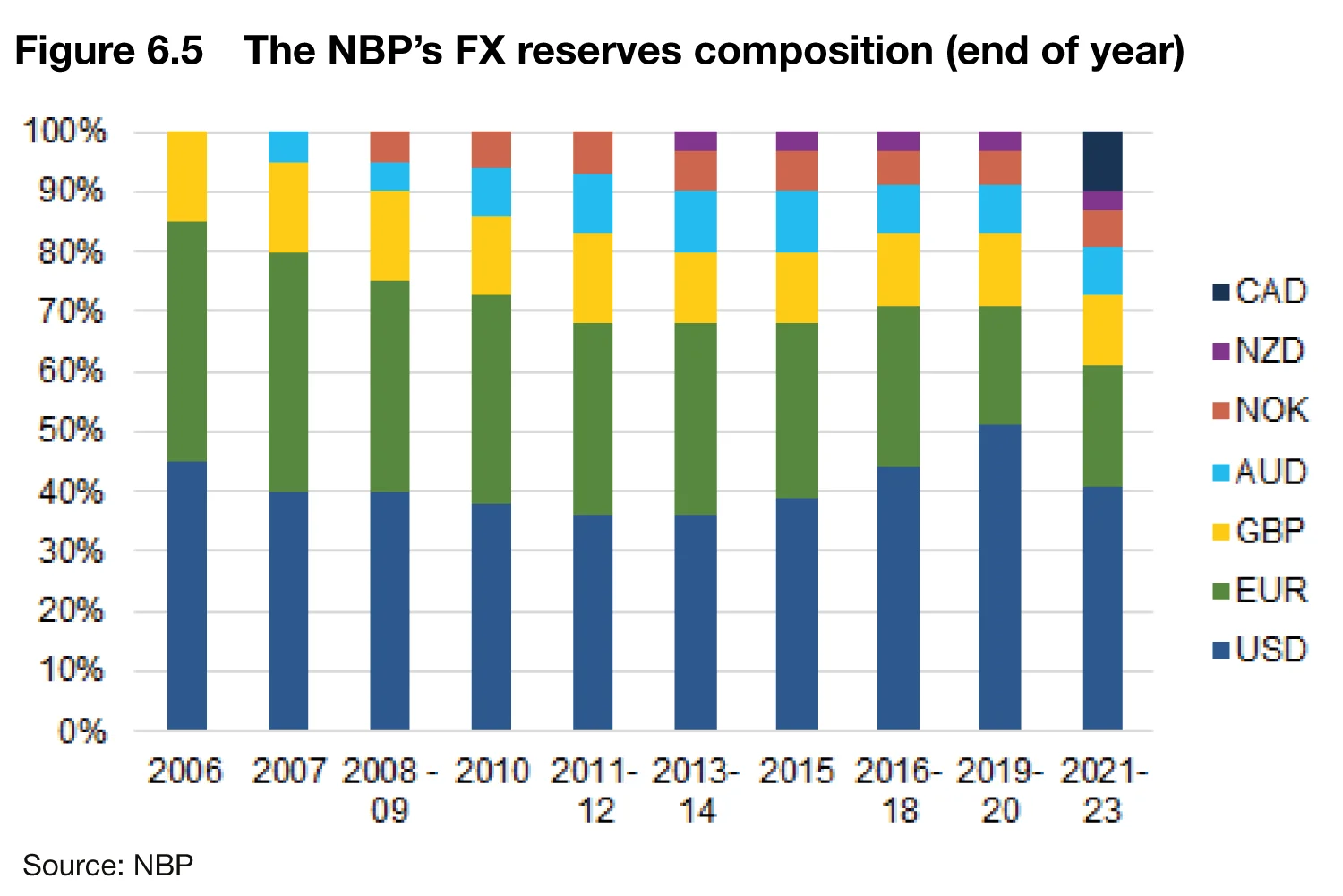

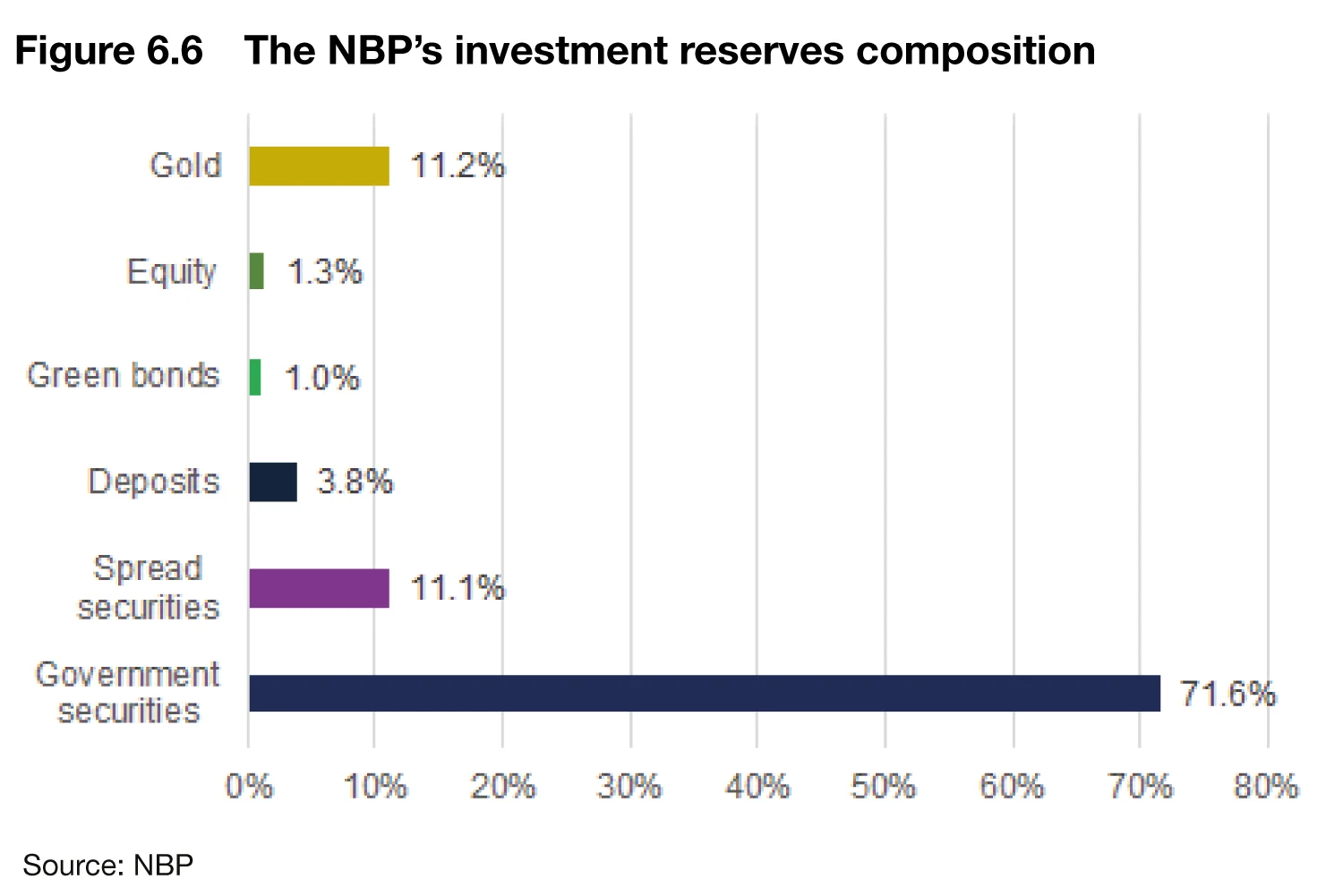

With a steady increase in portfolio size, we have gradually diversified the currency and instrument structure of our investments (figure 6.5). Beginning in 2006, with just the US dollar, euro and sterling invested mostly in government bonds in their respective markets, by the end of 2023, we have arrived at a portfolio that is broadly diversified among seven currency markets and a vast spectrum of instruments, including supranational and agency bonds, corporate bonds, equities, and green and sustainable bonds, which we tend to view as a somewhat separate category (figures 6.5 and 6.6). The primary factor driving our diversification efforts has been the hope of achieving a more beneficial long-term risk/return profile, both from risk reduction and potentially also return enhancement.

The NBP’s gold purchases: a marathon, not a sprint

Gold has a special place among the instruments we invest in, both on account of its characteristics – it is devoid of credit risk, it is not easily ‘debased’ by monetary or fiscal mismanagement of any country, scarce in supply and virtually indestructible – and perhaps also due to historical reasons. The daring evacuation of Polish pre-World War II gold reserves following the invasion of the Nazis in 1939 – which took them through Romania, Lebanon, France, the Sahel and ultimately to the UK, US and Canada – is still vividly, if painfully, remembered, since the entire stock saved from the war was shortly thereafter completely spent by the newly established Communist authorities.

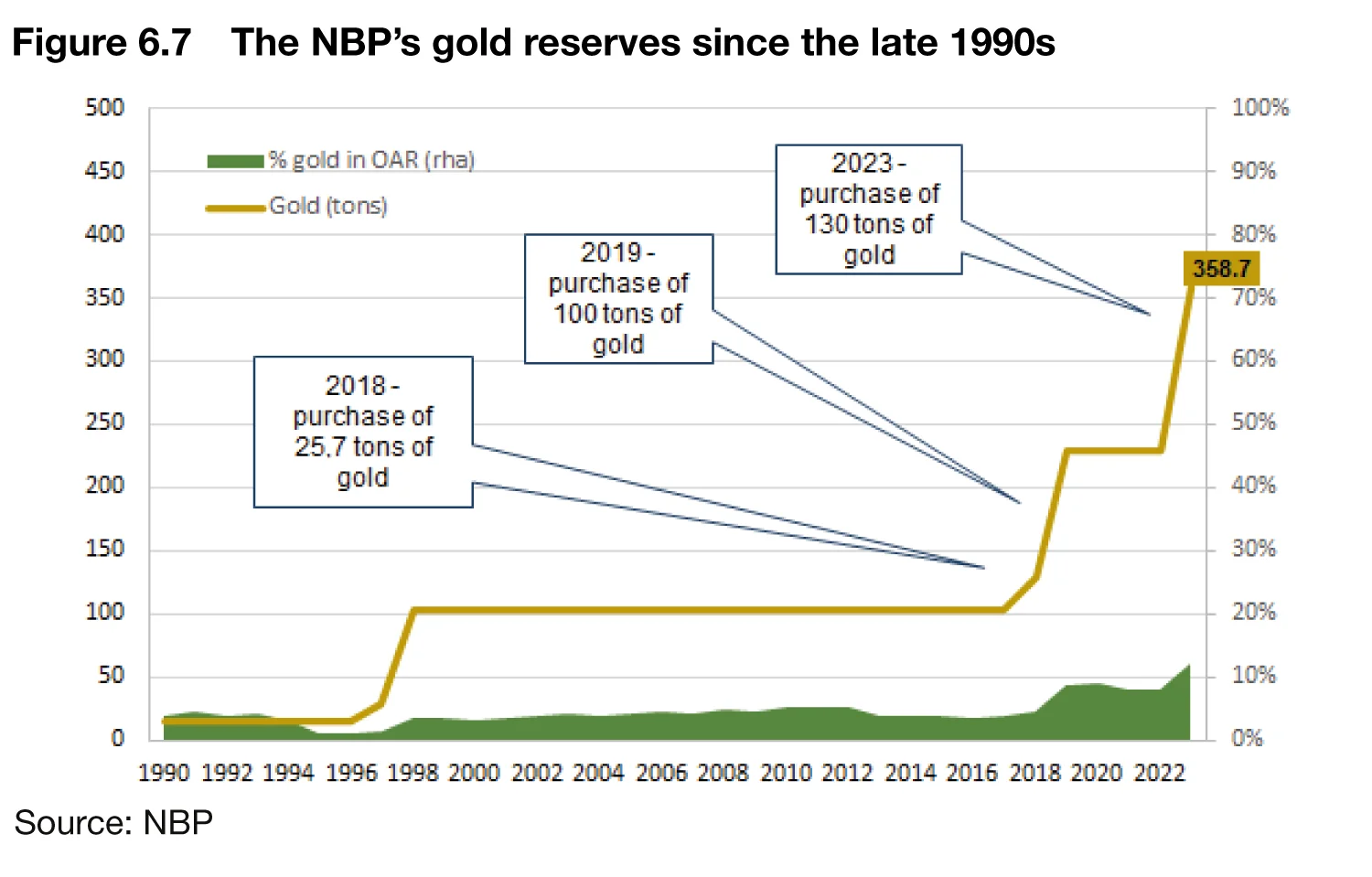

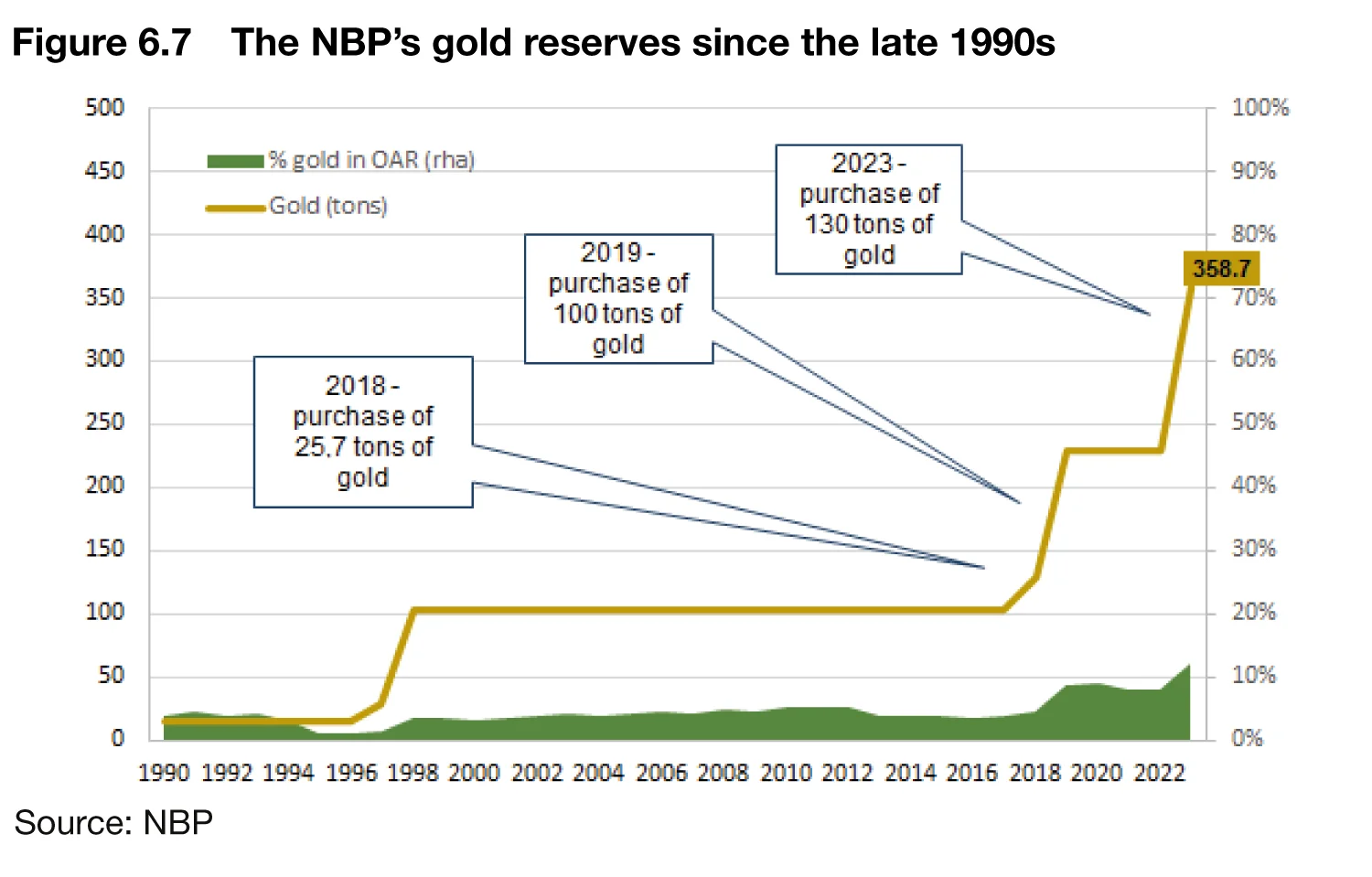

Thus, the NBP emerged from the post-Communist transition in the early 1990s with virtually no gold reserves. A small stock of roughly 15 tons had been maintained throughout the 1990s, until eventually a decision was made that the FX reserves portfolio (approximately $24 billion at the time) had become large enough to allow a build-up of gold holdings. The time was opportune, as a number of central banks in developed markets, which for historical reasons entered the era of great moderation with high gold reserves, began liquidating parts of their stocks. The NBP, in turn, was eager to rebuild its holdings, which – as the thinking went – would shore up foreign investors’ confidence in the currency and potentially also the broader economy.

After the purchases in the late 1990s, which brought the NBP’s gold holdings to roughly 100 tons, precious metal reserves remained practically unchanged, the vast majority of which was kept at the Bank of England (BoE), where it could be placed in deposits with other central banks and also commercial counterparties.

By 2018, the NBP’s total foreign reserve assets had grown to over $113 billion, making us sufficiently confident that we had enough latitude to start building up an allocation to the precious metal that would see us moving closer in line with averages seen among our peers in Europe and across the world. This process would ultimately involve several steps and multiple rounds of purchases, with intermissions for taking stock and evaluating (figure 6.7).

The first step in this process was taken in 2018. Specifically, from mid-July to the end of October of 2018, the NBP purchased 25.7 tons of gold. Back in 2018, we felt that we had not been active in the market for almost two decades, and thus we proceeded cautiously, spreading the overall purchase roughly evenly in batches, but ultimately found that finding a selection of counterparties offering competitive bids was not that difficult, and the overall market liquidity seemed encouraging. The newly acquired gold was again deposited at the BoE and – market conditions permitting – was invested with our counterparties. After finalising the purchases, our total gold holdings increased to 128.6 tons, and accounted for almost 5% of the NBP’s foreign exchange reserves. This put us in the 25th position (previously 33rd) in terms of total gold holdings in tons among central banks worldwide, and at the 13th position (previously 16th) among central banks in Europe. However, the share of gold in the NBP’s foreign exchange reserves continued to remain below the overall average for central banks (10.5%), and significantly below the average for European countries (20.5%).

Thus, from mid-May 2019 to the end of June, we followed suit with another round of purchases, this time to the tune of 100 tons, four times the target from the year before. Not only was the size a bigger challenge, but also market volatility proved more testing – shortly after we began making trades, the price moved abruptly, gaining almost 20% within a few months. Luckily, we were able to conclude this round of purchases, as well, with the newly acquired gold ultimately transferred from the BoE to the NBP’s vaults, to provide some degree of storage diversification.

Having concluded two rounds of gold purchases, we entered what will undoubtedly be remembered as one of the most challenging periods in the NBP’s history, marked by the successive waves of the Covid pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a considerable – if temporary – spike in both global and domestic inflation. Throughout this challenging time, our gold investments have served us well – a point we shall return to below – reaffirming the management board’s view that we should continue expanding our gold holdings with the goal of aligning the composition of our portfolio closer to global and especially European averages, keeping in mind the need to diversify storage locations.

Hence, from the beginning of April 2023 to mid-November, the NBP’s dealers have purchased an additional 130 tons of gold, bringing the total stock to 358.7 tons, and just above a 10% share of our overall reserve assets portfolio (figure 6.7). The newly purchased gold was deposited with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, so that our holdings could be roughly evenly spread across three locations, both international and domestic, in line with the practice followed by other central banks.

In 2024, the NBP’s management board passed a motion to increase the share of gold in our official reserve assets to 20%, which would entail purchasing 226 tons of gold, as a result of which, the size of the NBP’s gold reserves would increase to approximately 585 tons, making Poland the 11th largest holder of gold in the world and the 6th in Europe. This last project is, of course, still under way.

Gold purchases: a risk-centred view

Having laid out above the historical context and the qualitative arguments behind increasing gold reserves, we now turn to the empirical evidence and a more quantitative, risk-centred analysis.

This requires us to unpack the argument formulated in the introduction that, despite being commonly perceived as a strategic reserve asset, gold is actually characterised by relatively high volatility. Although this might be a cause for concern, we should first of all remember that, from the perspective of a strategic allocator of capital across many asset classes, it is not so much the volatility of an asset on a standalone basis that matters most, but rather the way that an asset’s risk/return profile interacts with other instruments in the portfolio. Secondly, numeraire matters: as a Polish central bank, we report financial results in the domestic currency, the Polish zloty (PLN). Thus, what we are often interested in is not only the risk/return profile of an asset expressed in a foreign currency, but also in the zloty.

Looking specifically at gold, its overall market risk is driven by essentially three factors: (i) the volatility of the gold price expressed in USD (comparable, as we have seen, to the volatility of stock price indexes – or even greater); (ii) the volatility of the USD/PLN exchange rate; and (iii) the interdependence between both of the first two factors. We believe gold’s high volatility is, in a sense, the price that buyers need to pay for its favourable investment characteristics – primarily its tendency to increase in value during periods of increased market tensions when other assets decline. These properties mean that gold can have a positive impact on the overall market risk profile of a foreign exchange reserves portfolio.

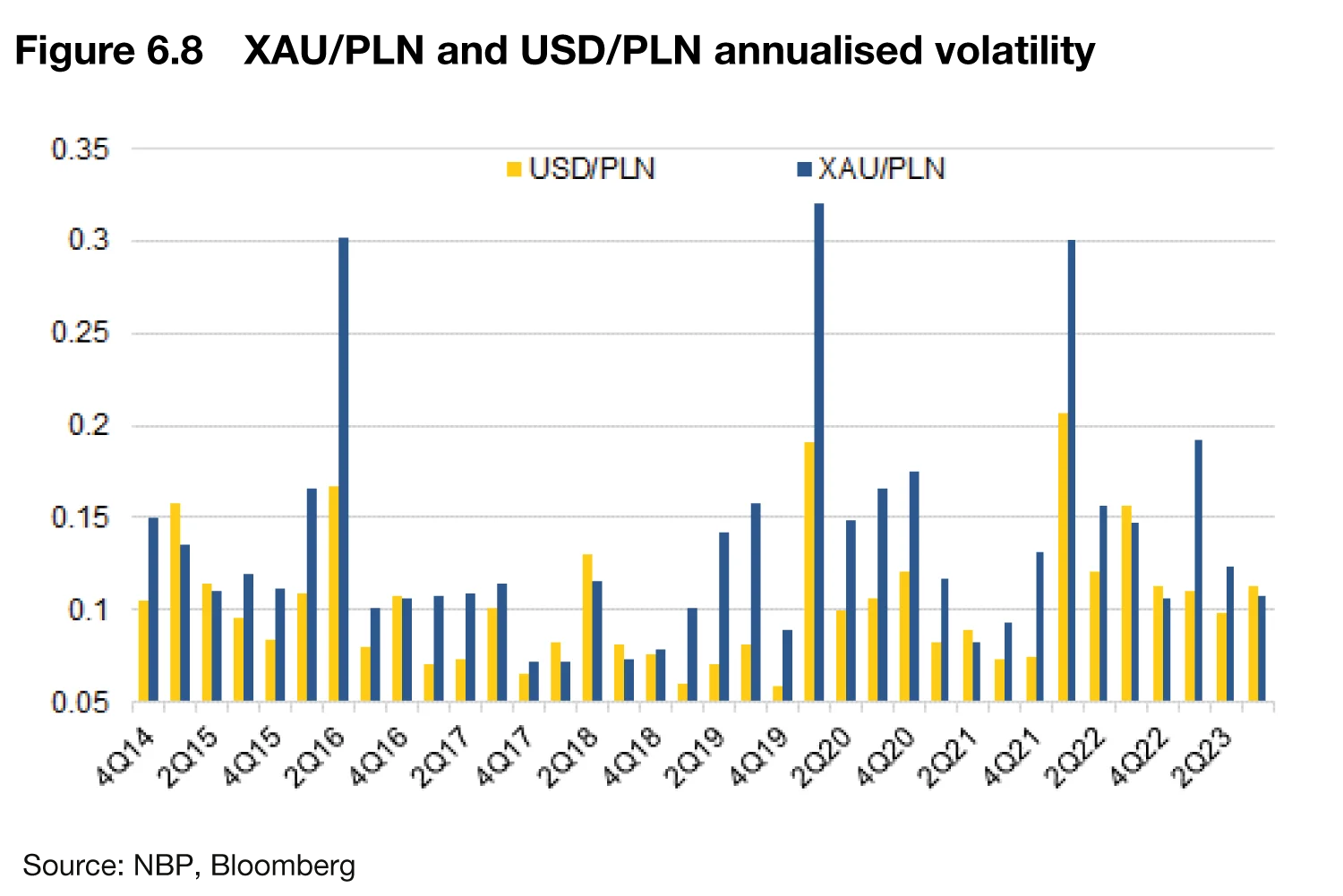

Now, as is clear from figure 6.5, the NBP’s reserves are heavily tilted towards the US dollar, which dominates the overall risk profile. While there are many good arguments in favour of maintaining a large chunk of reserves in USD (deep and liquid capital markets, good credit risk and – especially now – one of the highest yields across the developed markets space), it does tend to be one of the more volatile currency crosses in our portfolio. Whenever the zloty appreciated, some of the biggest moves tended to be on the USD/PLN. Interestingly, though, despite the fact that the volatility of the gold price in PLN tends to be higher than the volatility of the USD/PLN exchange rate, due to the relatively low correlation between the two rates (the average annual correlation over the last 10 years being 0.36), gold serves as a diversification factor for our reserves in US dollars (figures 6.8 and 6.9).

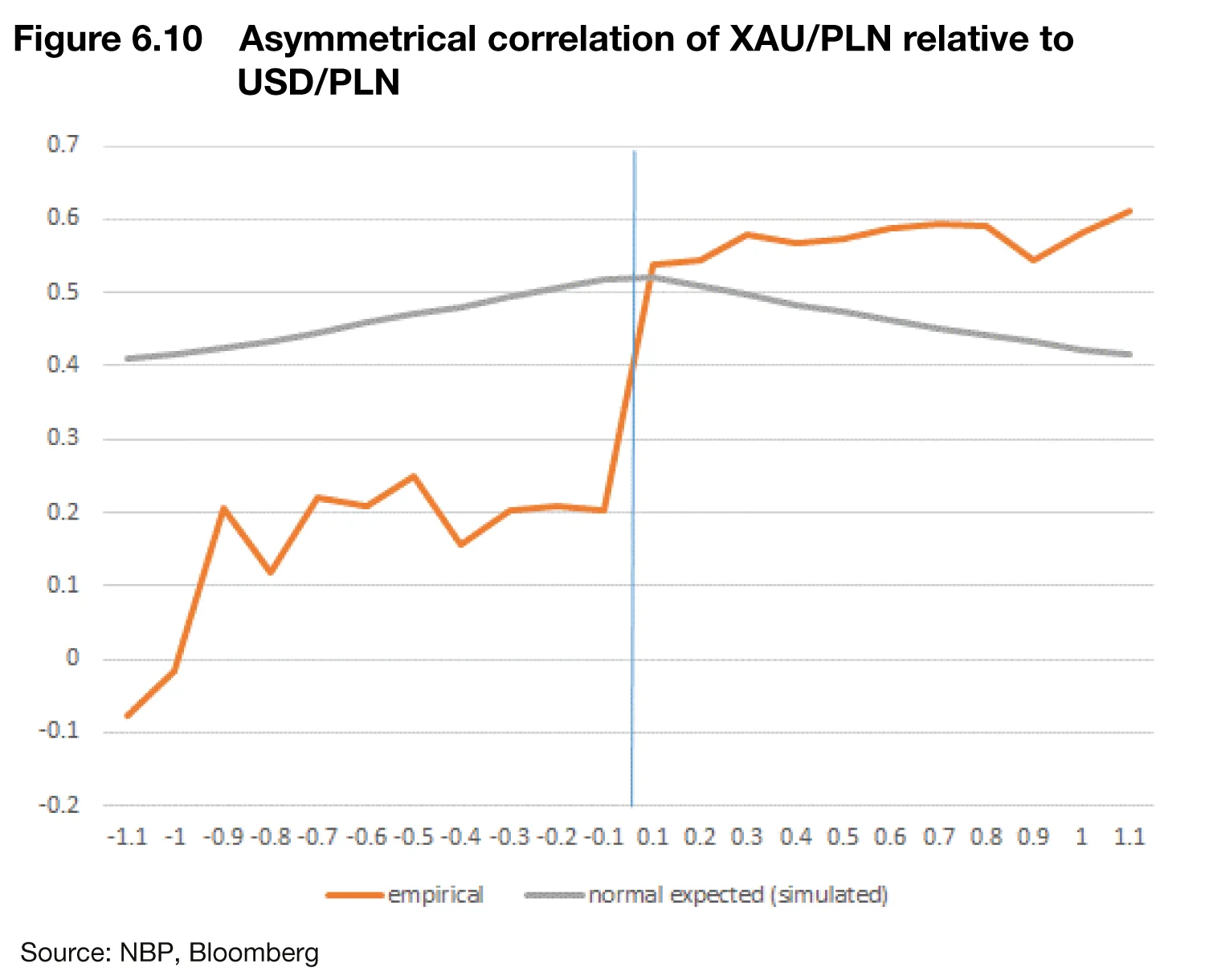

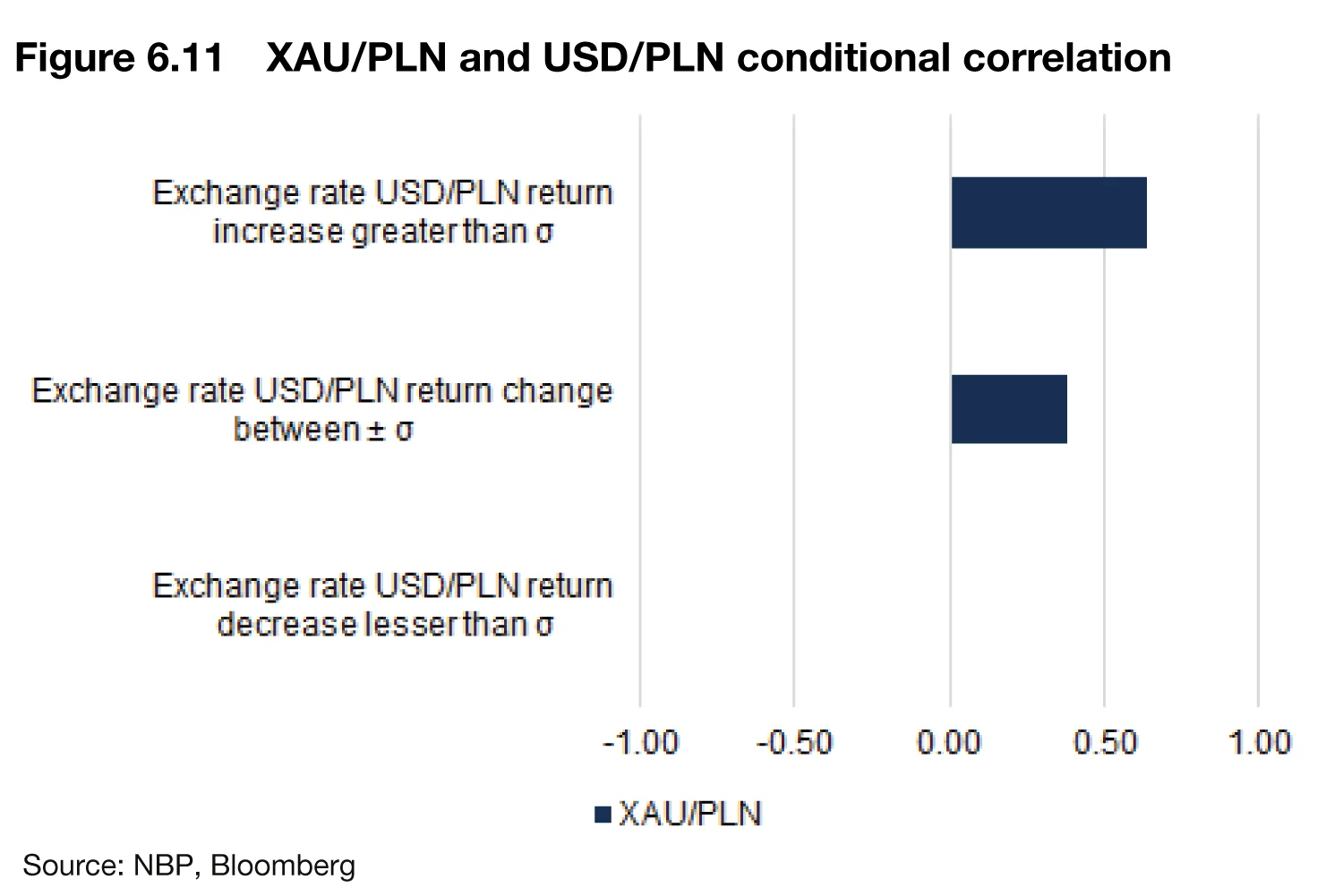

However, there is more nuance to the diversification story. After all, we like diversification only during ‘bad’ states of the world, but during ‘good’ states of the world, we would prefer to see all our assets performing together. This is certainly a tall order, but, interestingly, gold does have a rather uniquely asymmetric correlation profile with the USD – which is exactly what we want (figure 6.10). After all, the NBP should strive to diversify or hedge the risk of a strong appreciation of the Polish zloty, but not necessarily depreciation, which increases the value of reserves expressed in PLN and, as such, is beneficial for the NBP’s profit and loss as well as the central bank’s capital position. Indeed, our analysis of a dataset spanning the last 10 years affirms this relationship for the price of gold expressed in PLN relative to the USD/PLN exchange rate: in the case of PLN appreciation against the US dollar, gold will play a diversifying role for the reserves portfolio. Conversely, in situations where the PLN depreciates against the USD (resulting in a positive return from the USD/PLN exchange rate), gold investments have the potential to increase the value of our reserves in USD.

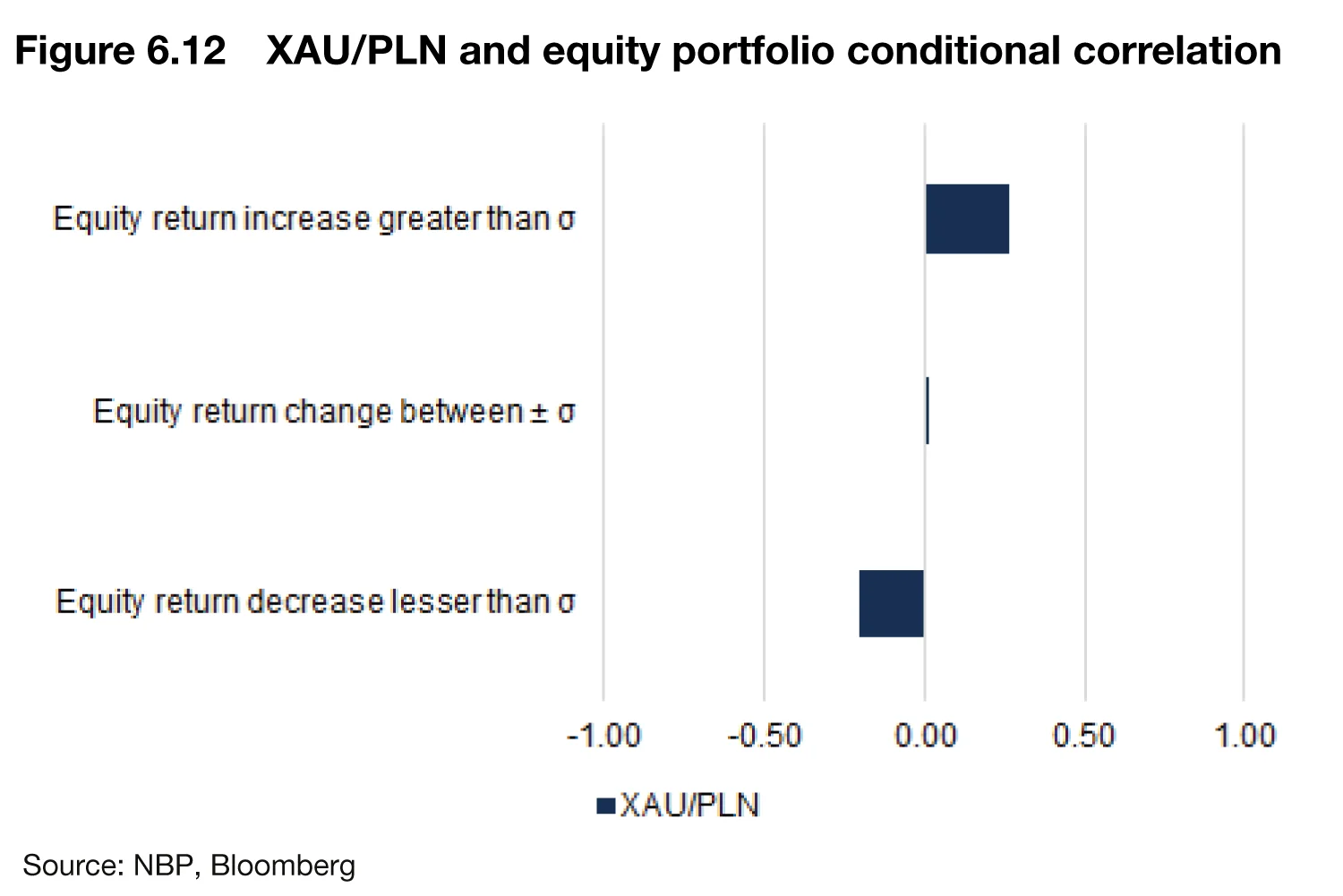

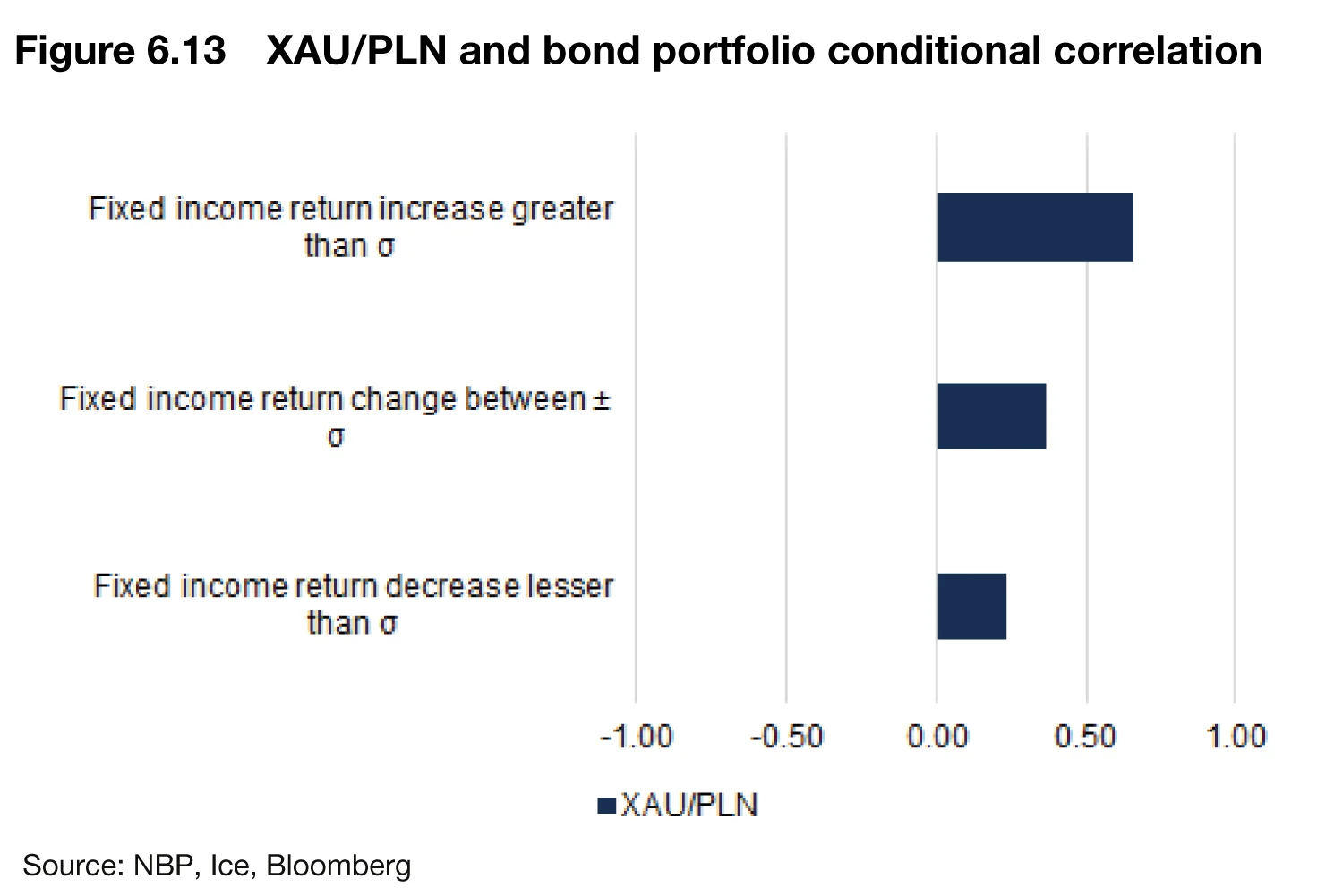

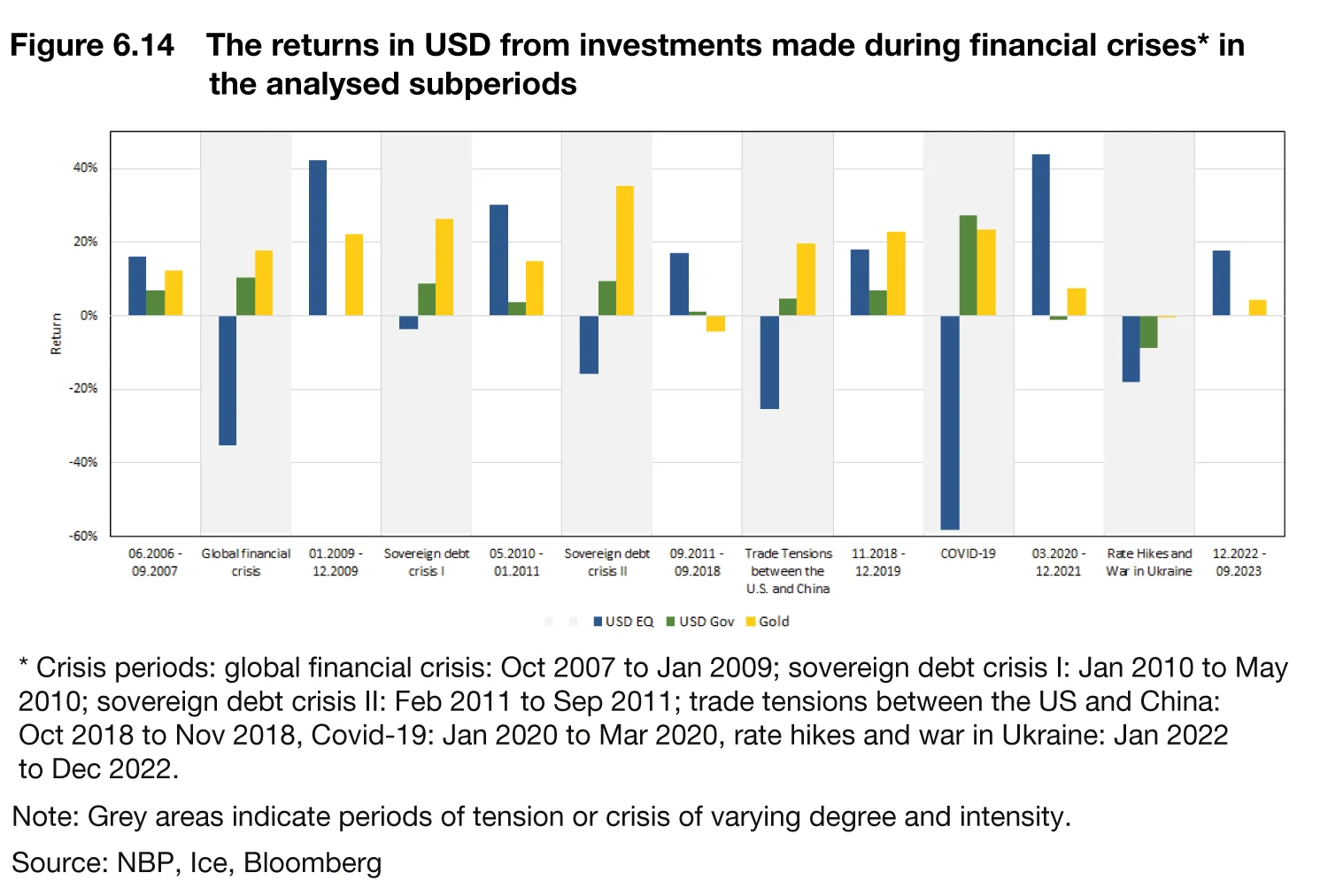

The relationship described above was particularly evident during periods of heightened systemic risk, and also applied to other assets in which the NBP invests, notably equities (figures 6.12 and 6.13). During crisis periods, gold serves as a hedge against elevated inflation and the decline in stock indexes (figure 6.14). Likewise, during market stabilisation periods, gold represents a favourable alternative to other investments, typically achieving higher returns than bonds.

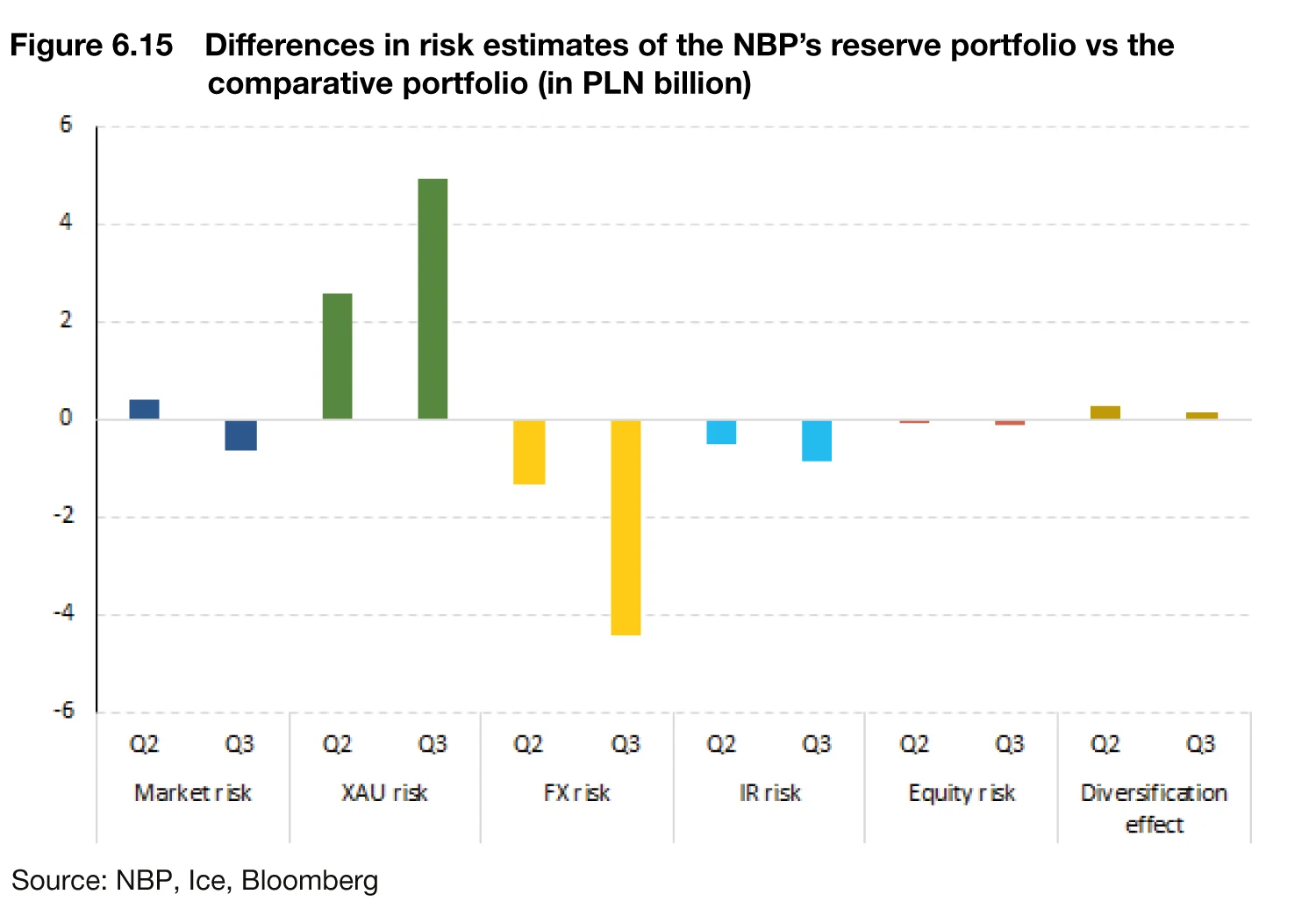

The gold purchases executed by the NBP in the second quarter of 2023 contributed to a slight increase in the level of market risk (measured using value-at-risk) estimated at the end of June 2023.3 However, by the end of the third quarter, the increase in gold reserves resulted in a minor decrease in market risk. In both quarters, the expansion of gold reserves translated into an elevation of the diversification effect (figure 6.15), estimated as undiversified value-at-risk4 less the VAR estimate. Our gold purchases at the expense of other currency reserves resulted in a reduction of all risk categories (except for the risk of gold price changes), with the most significant change observed in exchange rate risk. This is due to the fact that the dominant risk factor in the NBP’s foreign exchange reserves portfolio is the fluctuation of the USD/PLN exchange rate.

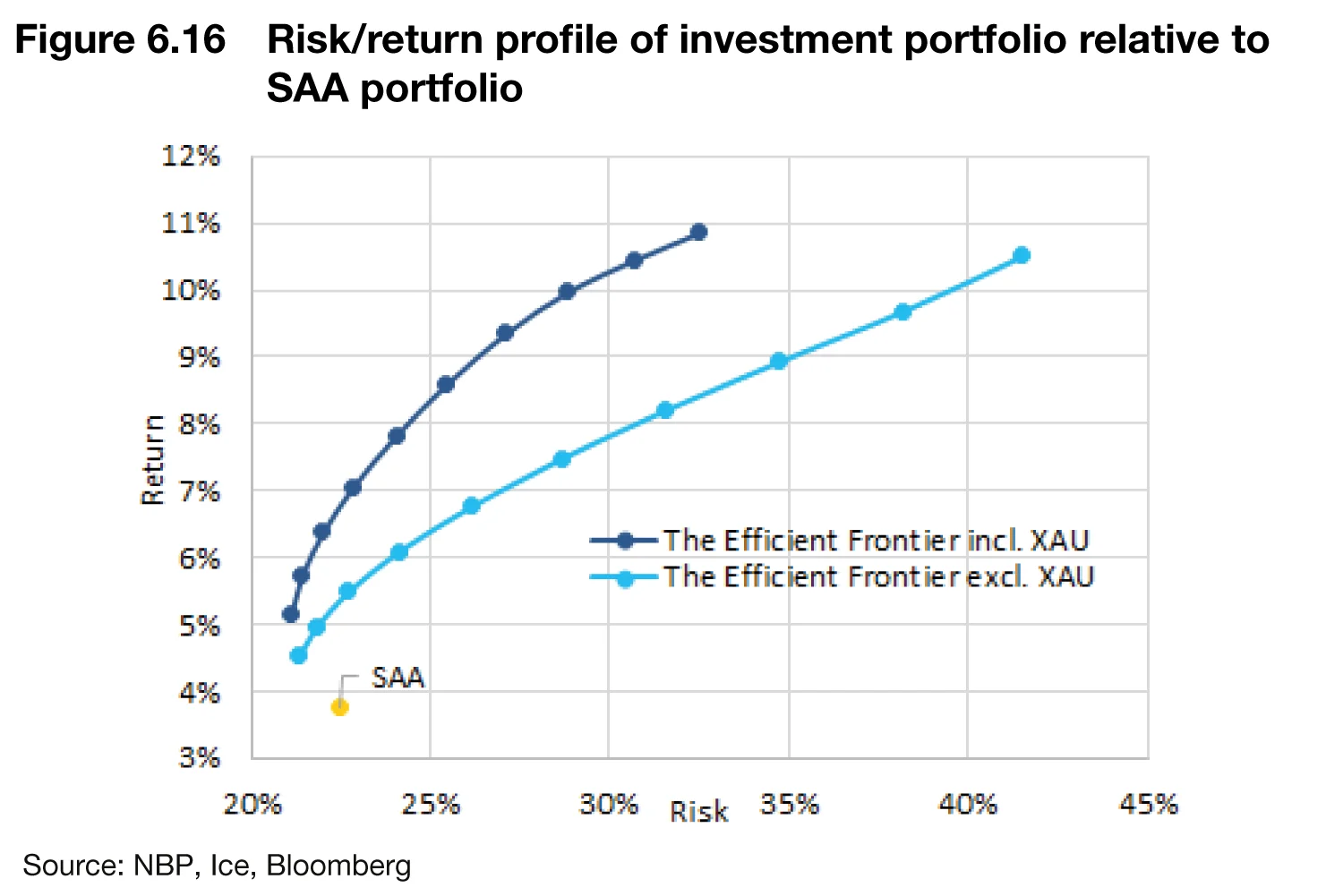

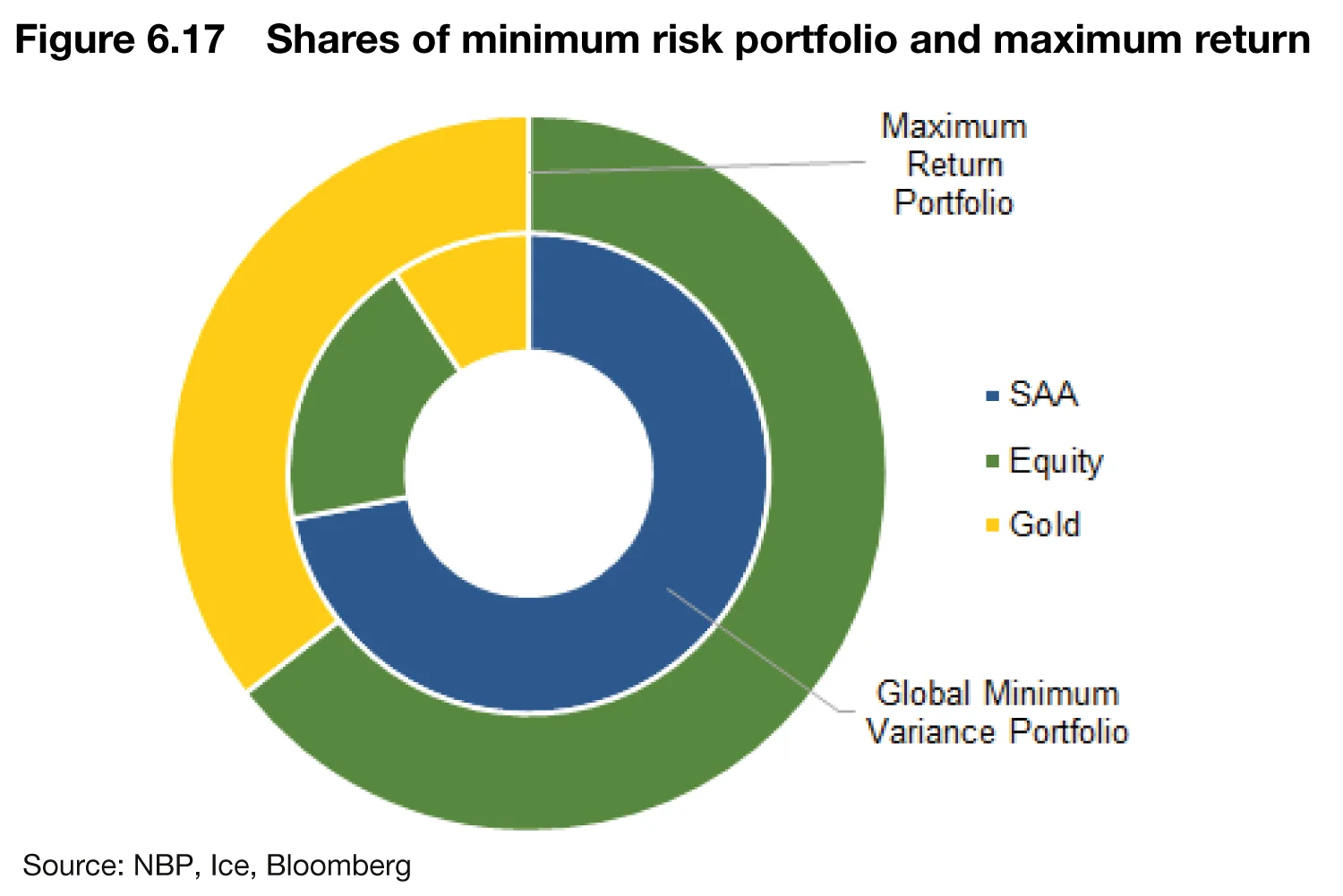

Looking at the risk/return trade-off, including gold in portfolio composition optimisation analyses, raises the efficiency frontier, enabling an improvement in the risk/return profile of the foreign exchange reserves portfolio. The optimal allocation of gold in the minimum-risk portfolio is around 9–10%, and increases as we move along the efficient portfolio curve towards a portfolio with maximum return (where it reaches 35% – see figure 6.16).

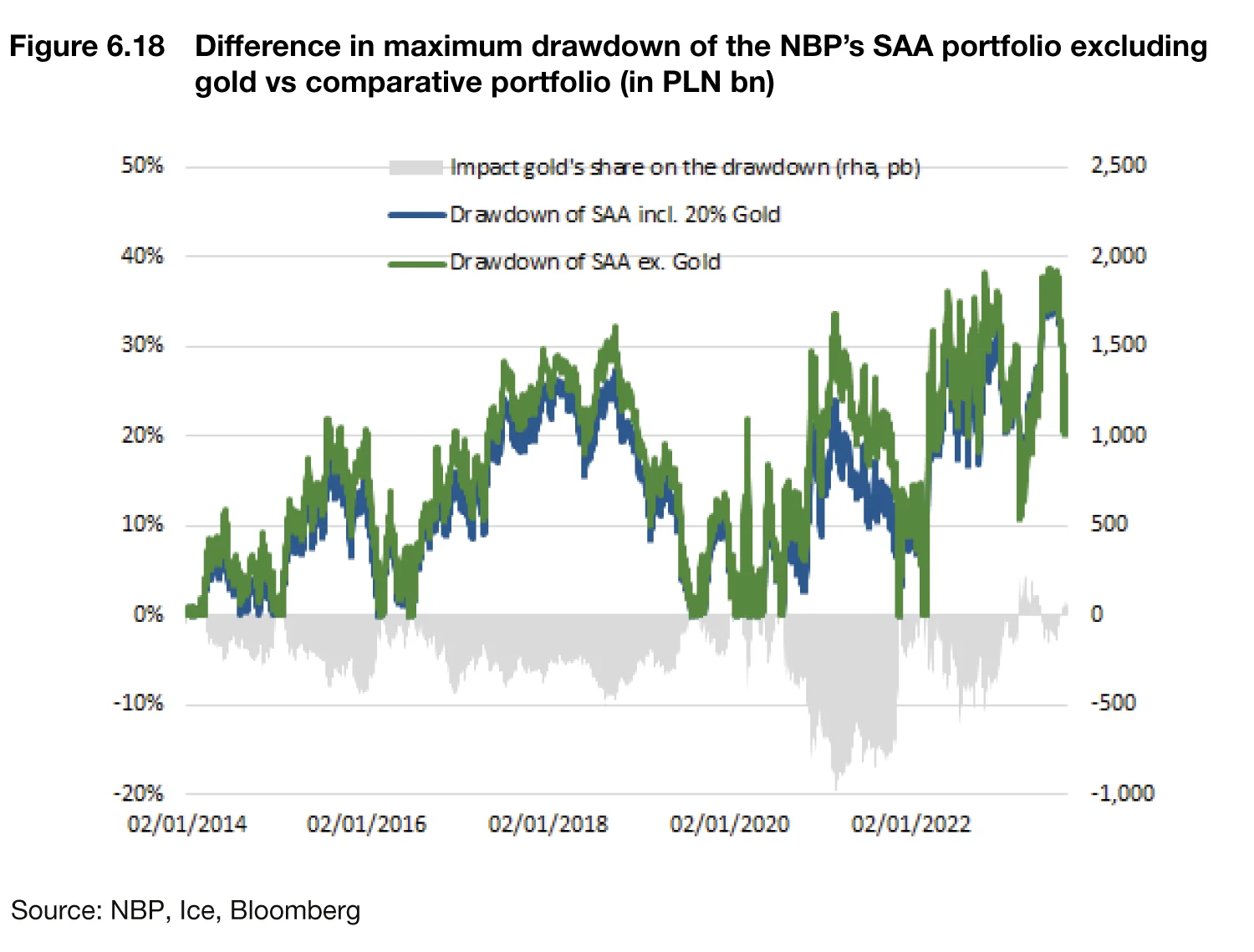

The diversification role of gold described above is additionally confirmed when comparing the historical drawdown of our reserves portfolio with gold against the: (i) reserves portfolio including 20% of gold allocation; and (ii) benchmark portfolio that does not include gold. The lower the magnitude of the maximum drawdown, the smoother the growth path of returns over time and the lower the risk of significant declines in the portfolio value. As is clear from figure 6.18, throughout the analysed period, a 20% allocation to gold would have meaningfully dampened the extent of drawdowns – especially in periods of elevated market turmoil.

Gold as an inflation hedge

Finally, coming out of the recent period of a strong uptick in inflation across the world, we cannot ignore the impact that inflation can have on asset returns. Although figure 6.2 suggested that all our asset classes – stocks, bonds, gold and even T-Bills – delivered positive real long-run returns, there is a difference between beating inflation and hedging against it. This point is particularly relevant for the NBP as an investor with a portfolio dominated by fixed income securities and an investment horizon that is likely to extend through a multitude of market and economic regimes. Conventional bonds, which pay out contractually fixed coupons, tend to suffer whenever inflation spikes – both because the coupons are now worth less in real terms and because those coupons will need to be discounted at higher rates (which tend to rise as well whenever inflation increases). With equities, the argument is less clear-cut because their cashflows are based on corporate earnings that might rise in line with inflation, thus offering some portfolio hedging. However, higher inflation might also impair performance if corporations are unable to maintain mark-ups and increase profits – in which case, equities will suffer in an inflationary regime.

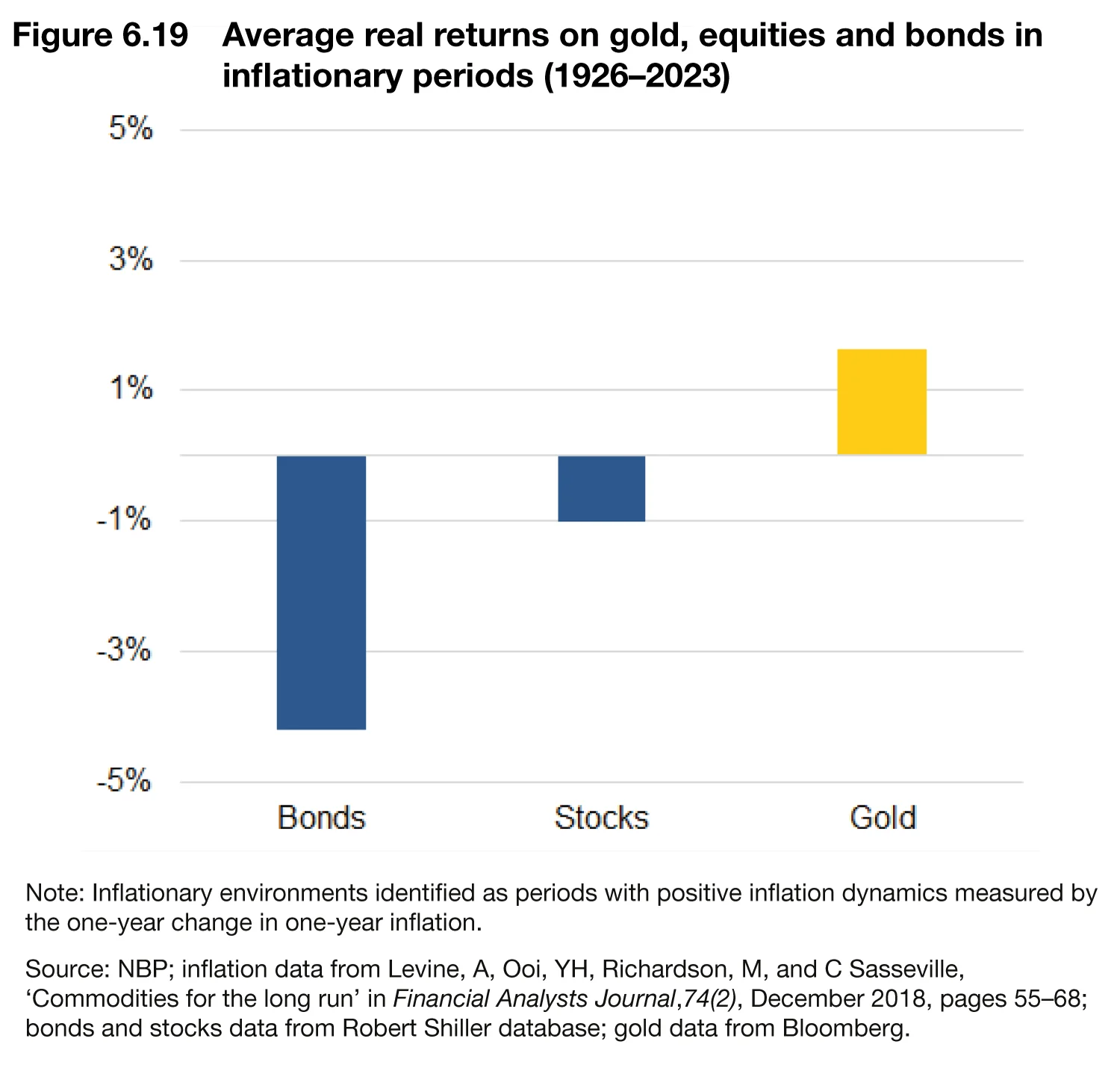

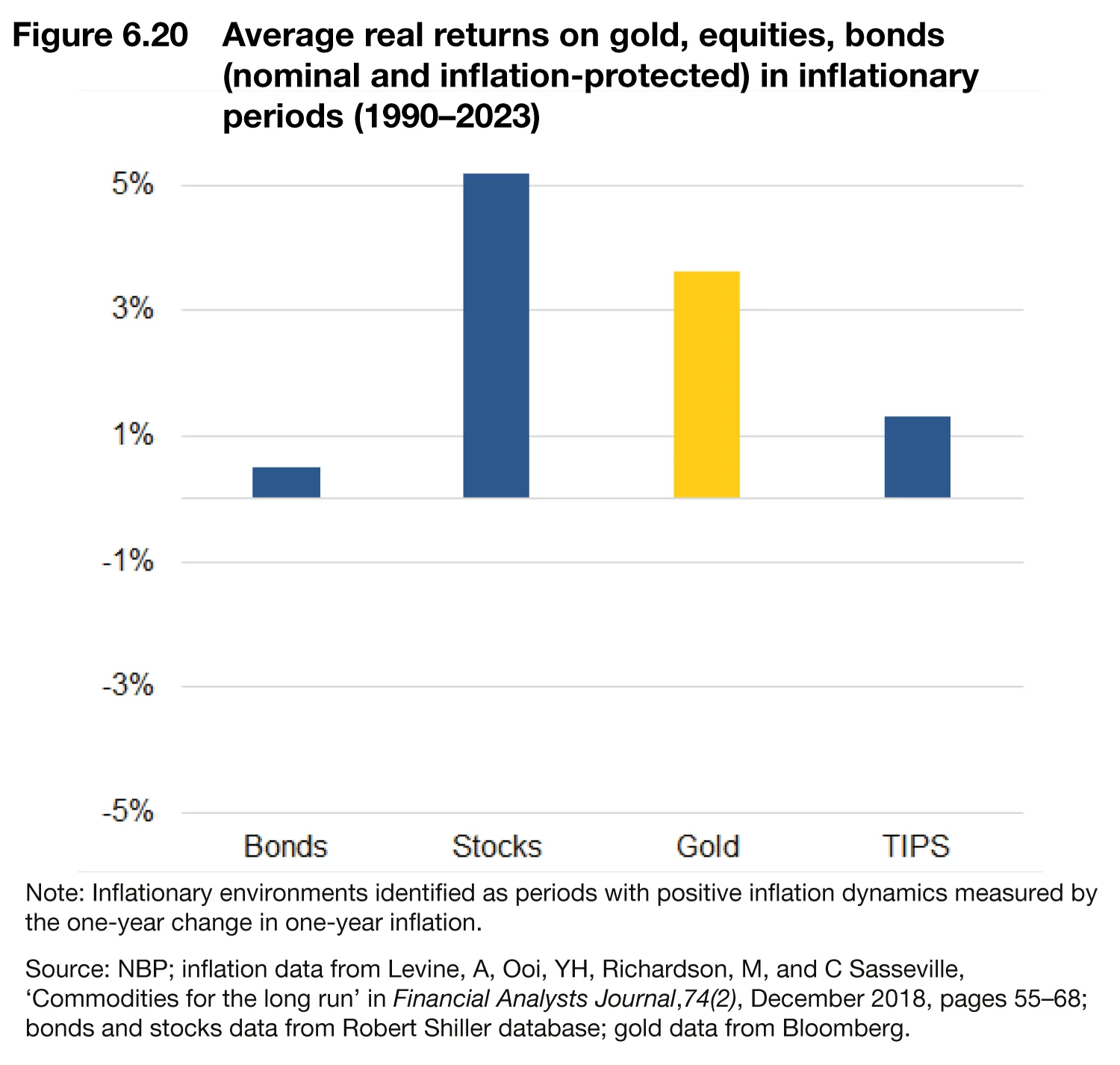

A careful look at nearly a century of evidence shows that neither bonds nor equities have offered effective protection against inflation, since their real returns tended to be negative whenever inflation was on the rise (figure 6.19). More promisingly, however, the average real return on gold in periods of rising inflation was comfortably positive, illustrating the potential of the precious metal to protect the portfolio in periods when other asset classes suffer. Over a shorter, 30-year period, real returns on equities and bonds in inflationary environments appear to improve. However, this outcome may be driven by a secular decline in real rates, which has boosted returns on both asset classes. Still, even in these historically unusual past 30 years, real returns on gold in inflationary periods have been quite robust. That gold proved to be a superior inflation hedge to conventional bonds is perhaps no big surprise. However, figure 6.20 shows that real returns on gold also exceeded the returns on inflation-protected securities (for which we have data starting in 1997), which explains why the NBP treats gold as the inflation hedge of choice.

Conclusion

Drawing heavily on historical accounts and empirical analyses, we hope to have shed some light on the NBP’s thinking about gold as a strategic reserve asset. In particular, we hope it is clearer now that, although gold has historically been quite volatile, and certainly less attractive than bonds on an isolated, risk-adjusted basis, its true value added can only be appreciated fully in a portfolio context. Specifically, in the case of the NBP, an allocation to gold diversifies the risk associated with our USD investments, and does so in an asymmetric way – ie, dampens the effects of PLN appreciation vis-à-vis the dollar, but improves mark-to-market valuation in periods of a weaker zloty. Finally, gold serves as an effective inflation hedge that may be of particular relevance to a long-term investor who lives by the adage ‘you ain’t seen nothing yet’. Against this background, there is little doubt that gold will continue to play an essential role in the NBP’s FX reserves portfolio.

Notes

1. The authors contributed equally, and are listed alphabetically. The views expressed are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the official stance of the National Bank of Poland.

2. In that spirit, for example, during a debate in US Congress, Republican representative David Cawthorn opined that “the shift from a gold standard to a fiat currency began to starve America’s financial pre-eminence”, and explained his argument by saying: “You cannot inflate gold, but you can print money out of thin air.” (Congressional Record, House, H3783, March 17, 2022).

3. The comparative portfolio has the gold reserves equivalent to the investment portfolio gold reserves as of end Q1 2023 and the same market value as the investment portfolio in Q2 2023 and Q3 2023. In subsequent quarters, Q2 2023 and Q3 2023, the comparative portfolio FX reserves are increased by the amount equal to the gold purchased in said quarters, but maintaining the same FX structure as the investment portfolio.

4. VAR calculated without considering the impact of correlation between individual risk categories.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com