Reserve management in China: foreign reserves, renminbi internationalisation and beyond

Trends in reserve management 2021: survey results

Reserve management in China: foreign reserves, renminbi internationalisation and beyond

Emerging market debt during interest rate increase cycles: analysis for reserve managers

Interview: Jarno Ilves

How the Fed’s Fima addressed the 2020 dollar liquidity shortage

How derivatives can add value to modern reserve management

China’s foreign exchange reserves and reserve management were the focus for considerable and sustained political attention and economic analysis during the first decade of the 21st Century. This was a period that saw a phenomenal increase in the level of foreign reserves, a growth unprecedented in economic history. Although Beijing’s reserves stock has fallen by almost a quarter in recent years, China remains the biggest holder of foreign exchange reserves in the world by a significant margin. At the same time, and this again was a move of considerable historical importance, the Chinese authorities began a programme of promoting the use of China’s currency, the renminbi, on the international stage.

This chapter will explore how China managed its reserves in the 2010s, particularly the second half of the decade after the stock market collapse in 2015. It will first examine the institutional structure that underpins its management regime, before assessing the dynamics of its investment strategy and how reserve management has impacted monetary policy and wider macroeconomic management in China. This is followed by an examination of China’s efforts to promote the renminbi as a global, and also digital, currency.

The 2015–16 haemorrhage

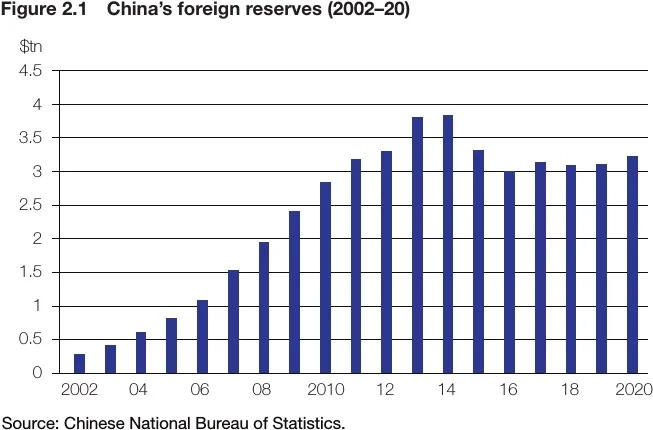

It is hard for anyone not to be dazzled by the explosive increase of China’s foreign reserves since the 1990s. In fact, the stock of reserves increased at the blistering rate of 30%, on an annualised basis, over the two decades from 1994 to 2014 as a result of enormous trade growth and an influx of foreign investment. China overtook Japan as the leading holder of reserves in 2006 and has not looked back, with reserves peaking at $3.99 trillion in June 2014 (see Figure 2.1).

However, the seemingly unstoppable trend was disrupted by a series of events in the financial markets, and the resulting regulatory response, over the course of 2015 and 2016. It began with a stock market meltdown in mid-2015 that saw the benchmark Shanghai Composite Index eventually plunge over 40% by September. To make matters worse, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), China’s central bank, devalued the renminbi by almost 2% against the US dollar in August 2016. The combination of an economic slowdown and stock market crash triggered an acceleration of capital outflows that saw foreign reserves fall by just over $980 billion from a peak in June 2014 to January 2017.11 See “Being Xi Jinping: The Difficult Art of Juggling Growth and Control after China’s Communist Party Congress,” South China Morning Post (10 October 2017). This at least partially contributed to major international credit ratings agencies downgrading China’s sovereign credit ratings: Moody’s in May 2017 (for the first time since 1989) and Standard & Poor’s in September 2017 (for the first time since 1999). Since then, reserves have hovered above $3 trillion, reaching $3.2 trillion by the end of 2020. However, this is still more than twice that of Japan’ reserves.

Institutional structure of reserve management

The agency tasked with the management of China’s reserves is the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (Safe). Safe was established in 1979 as China opened up to the global markets, and became a PBoC subsidiary in 1994. The PBoC had experimented with a more diversified institutional structure in managing China’s ballooning reserves in the 2000s by establishing its own investment vehicle, Central Huijin, in 2003 and a sovereign wealth fund, China Investment Corporation (CIC), in 2007. However, the PBoC lost a turf war with the Ministry of Finance, which seized ownership of both Central Huijin and the CIC around 2007.22 Hui Feng, “The Three-Trillion-Dollar Question,” Central Banking, XXI (4), 26–30. See also Stephen Bell and Hui Feng (2013), The Rise of the People’s Bank of China: The Politics of Institutional Change (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011). Subsequently, Safe became the exclusive manager of the stock of reserves already on the central bank’s balance sheet, as well as any additions.

Over the years, Safe has become an increasingly professional investor on the global scene. The credit here should go to Zhou Xiaochuan, who was governor of the PBoC from 2002 to 2018. Zhou combined the skills of the consummate technocrat with an aspiration to modernise central banking in China, of which reserve management was an important part. Safe’s ascendence also benefited directly from the consecutive directorships of Hu Xiaolian and Yi Gang (who succeeded Zhou as governor of PBoC). Working together, they helped establish an internal governance framework and an international and professional team that could achieve the daunting task of managing the world’s largest foreign exchange reserves. Compared with the norm for the corps of Chinese bureaucrats, often recruited through personal or familial connections and political loyalty, the development of the investment team at the Safe has been rather refreshing. As of 2021, this staff includes returnees from Wall Street investment banks, chartered accountants from the “big four” and Ivy League PhDs, all fluent English speakers representing an effective balance between expertise and experience.

As well as recruiting highly qualified personnel, Safe has established a network of local operational units in all the major international financial markets: Singapore, Hong Kong, London, New York and Frankfurt, which enables it to trade on the global markets on a 24–7 basis. In addition, Yi introduced benchmarking for portfolio and risk management as well as performance reviews, which further beefed up its institutional capability. According to Safe, its annual average return from 1994 to 2015 was 4.55%, with the ten-year average return from 2006 to 2015 being 3.55%. It also won an award for Institutional Excellence from AsianInvestor magazine in 2015, who said: “Safe now has the best-defined goals among China’s big investors and among the best structures of institutions across North Asia. It has the best teams among government-sponsored investment groups.”33 “Why China’s Safe Stands out for its Investment Expertise,” AsianInvestor (21 December 2015).

Managing the pile

According to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), “safeguarding market security and providing liquidity when necessary” are the priorities of reserve management.44 BIS, “Reserves Management and FX Intervention,” BIS Paper No. 104 (31 October 2019). Indeed, Safe’s main approach to reserve management has been to ensure safety and liquidity, after which a certain level of return is sought.

To date, Safe has only disclosed a few details of China’s reserve assets, in its 2018 Annual Report.55 Safe, “Annual Report 2018” (2018). According to this report, by 2018 reserve assets made up 43% of China’s external financial assets. At the same time, Safe has endeavoured to diversify the currency structure of the reserves away from the dollar. The share of dollar-denominated assets reduced from 79% to 58% between 1995 and 2014, with the 2014 figure being even lower than the international average of 65%, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

There are two objectives for reserves management: political and commercial. First, Safe has to ensure it fulfils the international commitment and political purpose of the Chinese government. For example, in international terms, Chinese reserves were used to purchase bonds issued by the International Finance Corporation, a member body of the World Bank. China also participated in the establishment of FX reserve pools in a regional arrangement with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Japan and South Korea, as well as an emergency reserve arrangement with Brazil, Russia and India.

In addition, China’s reserves are used to finance its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a large-scale external investment programme focused on infrastructure, mainly in the form of entrusted loans. Safe established an entrusted loan office within its reserve management department, which was in charge of the capitalisation of key financiers for the BRI, including the Silk Road Fund, China–Latin America Capacity Fund, China–Africa Capacity Fund, China–Africa Development Fund, CIC, China Development Bank and the Exim Bank of China.66 See Hongyan Li, “Waihui Chubei Guanli Fuwu Guojia Zhanlue, Fengxian Fangfan Fangzai Shouwei [FX Reserve Management Serves National Strategies, Risk Management Tops List],” China Finance (January 2019).

Commercially, reserves are invested in both international and domestic financial markets, and also in equities and bonds. According to the head of the Safe’s reserve management department, equities have a larger share than bonds in its portfolio.77 ibid. In particular, Safe launched the Wutongshu Investment Platform in 2014 as its main investment vehicle for the domestic stock market. Since then it has been an important shareholder in a range of major banks and listed companies. However, this has also drawn criticism for a perceived conflict of interest from these operations, notably because the PBoC is part of the broad regulatory authorities of domestic stock market, and Wutongshu is effectively an interest entity of the central bank (via Safe). This positioned the PBoC as both referee and player in the market. On the other hand, the PBoC and Safe argue that Wutongshu not only undertakes commercial investment, but also serves as a market stabilisation fund of the government during times of volatility.

Renminbi internationalisation: a scorecard

After much hesitation, Beijing has embarked on a gradual but determined campaign to promote the renminbi as an international currency in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. This move was a result of frustrations from a dollar-dominated system that was seen to have at least partially contributed to that crisis. More fundamentally, however, it reflected the leadership’s ambition to develop and reinforce its growing economic might. This latter was also exploited by the PBoC, and especially by Governor Zhou, in gaining political support from the top to push through the liberalisation reforms that would be essential to internationalising the renminbi.88 Bob Davis, “Were China’s Leaders Conned?,” Wall Street Journal (2 June 2011). Beijing’s move to allow cross-border trade to be settled in the Chinese currency on a trial basis in Shanghai and Guangdong province in April 2009 can be seen as the starting point of the endeavour.

By deploying its resources strategically, Beijing has overseen a rapid expansion in the role of the renminbi in both trade and financial terms (see Box 2.1). This has been achieved through several mechanisms, including signing bilateral currency swaps, establishing offshore clearing centres and opening up domestic financial markets.

Box 2.1 A timeline of renminbi internationalisation

| 21 July 2005 | China initiates reforms by de-pegging the yuan from the US dollar. |

| 8 April 2009 | Cross-border trade allowed to be settled in renminbi on a trial basis in Shanghai and Guangdong province. |

| 24 March 2010 | The first multilateral currency swap agreement involving renminbi – the Chiang Mai Initiative – comes into effect. |

| 15 December 2010 | Russia becomes the first overseas market for renminbi trading. |

| 13 January 2011 | China’s qualified domestic enterprises are allowed to invest in foreign countries directly using the renminbi |

| 16 December 2011 | China launches pilot programmes for renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (RQFIIs). |

| 1 June 2012 | China starts direct trading between the yuan and the Japanese yen on the interbank foreign exchange market. |

| 9 April 2013 | China starts direct trading between the yuan and the Australian dollar on the interbank foreign exchange market. |

| 18 June 2014 | China starts direct trading between the yuan and the British pound on the interbank foreign exchange market. |

| 30 September 2014 | China starts direct trading between the yuan and the euro on the interbank foreign exchange market. |

| 17 November 2014 | China launches the Shanghai–Hong Kong Stock Connect scheme, allowing investors to trade eligible shares listed on each other’s markets through local securities firms or brokers. |

| 14 July 2015 | Foreign central banks, sovereign wealth funds and international financial institutions are granted access to the China’s domestic interbank bond market and interbank foreign exchange market denominated in renminbi. |

| 8 October 2015 | China launches the Cross-Border International Payment System (CIPS), a capital settlement and clearing service for cross-border yuan transactions for financial institutions. |

| 20 October 2015 | The PBoC issues its first offshore renminbi note in London. |

| 30 November 2015 | The IMF adds renminbi into its special drawing right (SDR) basket effective 1 October 2016. |

| 3 May 2016 | The PBoC expands its pilot programme for macroprudential management of cross-border financing from free trade zones to nationwide. |

| August 2016 | The World Bank issues the first SDR (special drawing right) bonds in China’s interbank bond market. |

| 16 May 2017 | Chinese and Hong Kong authorities jointly announce Bond Connect to enable bond trading between mainland and Hong Kong institutional investors. |

| March 2018 | Oil futures contract launches, denominated in yuan, on the Shanghai International Energy Exchange. |

| 17 June 2019 | China launches the Shanghai–London Stock Connect scheme, allowing eligible companies listed on the two stock exchanges to issue, list and trade depositary receipts on the counterpart’s stock market. ■ |

A currency swap is the exchange of currencies between two parties, a financial product developed in the 1970s that was originally designed to circumvent currency controls imposed by national governments. The purpose of the bilateral currency swaps between China and other countries and monetary authorities, however, is to provide liquidity to China’s counterparties in times of unexpected shortages of the dollar, such as the liquidity crunch after the global financial crisis. Over time, as such swap deals are institutionalised, they will help foster a wider acceptance of the renminbi in daily transactions on private and public levels within the counterparty countries. By 2020, China had signed currency swap agreements of approximately half a trillion dollars with over 60 countries.99 The Economist, “Redback on track,” (435)9193 (9 May 2020).

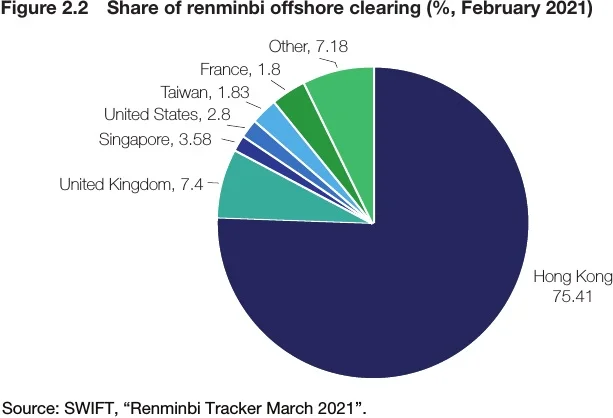

Since 2009, China has established more than 30 offshore clearing centres. These centres, often with renminbi clearing banks designated by the PBoC, are strategically located around the world to cover all time zones and large geographies. They are typically established in countries with strong trading and investment ties with China or in large financial centres. They not only provide a clearing mechanism to link offshore renminbi back to the mainland, but also promote offshore financial products and the creation of liquidity pools to facilitate financing and investment for foreigners in need of renminbi. Some of the key centres and partners include Hong Kong, London, Singapore, Taiwan and Europe. According to payments messaging service provider Swift, in February 2021 Hong Kong handled the majority (over 75%) of total offshore renminbi-denominated transactions, while London was the largest offshore centre for renminbi outside the Greater China region (see Figure 2.2).1010 Swift, “RMB Tracker March 2021” (2021) (available at https://www.swift.com/swift-resource/250411/download).

On the finance front, China has promoted active markets for offshore renminbi deposits, as well as developing investment opportunities for renminbi holders by encouraging the issuance of RMB-denominated bonds in offshore centres (so-called “dim sum” bonds) and, more importantly, opening up its $13 trillion domestic bond market, which accounts over half of those issued by emerging economies. Other major moves since 2016 have been various measures to open up China’s stock market to external renminbi investors, including connect programmes between the stock markets in Shanghai and London.

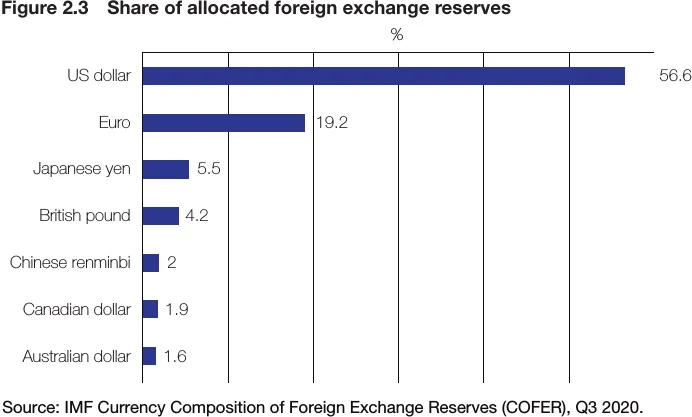

A major breakthrough came in November 2015 when China managed to persuade the IMF to add renminbi to its basket of currencies that makes up the SDR, an alternative reserve asset to the US dollar. There were wide concerns that such a move would include a currency into the benchmark for the SDR that was neither free floating nor free flow across borders given China’s capital control. In effect, the executive decision by the IMF board means that it recognises China’s efforts so far in financial reforms to make the renminbi “readily available”.1111 IMF, “Q and A on 2015 SDR Review” (30 November 2015). It also paved the way for the renminbi to become an international reserve currency. The central banks of Malaysia, Thailand, Chile and Iceland are reported to have acquired renminbi bonds as part of their foreign reserves.1212 Gary Smith, “Renminbi to Shape up Reserves Management Status Quo,” Central Banking, XXII(4) (2012: 61–66). European countries, such as France and Germany, are also thought to have added a certain amount of renminbi to their reserve assets.1313 Eshe Nelson, “Europe’s Central Banks are Starting to Replace Dollar Reserves with the Yuan,” Quartz (16 January 2018). According to the IMF, as of the third-quarter of 2020 almost 2% of foreign exchange reserves in the world were held in yuan, which is a huge leap considering the fact there was none before 2016 (see Figure 2.3).

The synergy arising from the combination of the above measures has seen the yuan move onto the centre stage of the international monetary system. In October 2015, it overtook the Japanese yen as the fourth-largest currency by value of payments, accounting for 2.79% of the total. However, the rise of the renminbi was dealt a blow in 2016. As discussed, the massive capital exodus as a result of stock market meltdown and devaluation of the renminbi forced Safe to deploy very tight capital control restrictions.1414 Stephen Bell and Hui Feng, Banking on Growth Models: China’s Troubled Path of Financial Reforms and Economic Rebalancing (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2022). While these measures did stabilise capital outflow, they also dented market confidence and the acceptance of renminbi-denominated assets, and therefore its internationalisation. Subsequently, the US-waged trade war since 2018, a sharp reduction in China’s overseas BRI funds and the Covid-19 pandemic since early 2020 has more or less disrupted China’s external trade and investment, with internationalisation of renminbi being collateral damage.

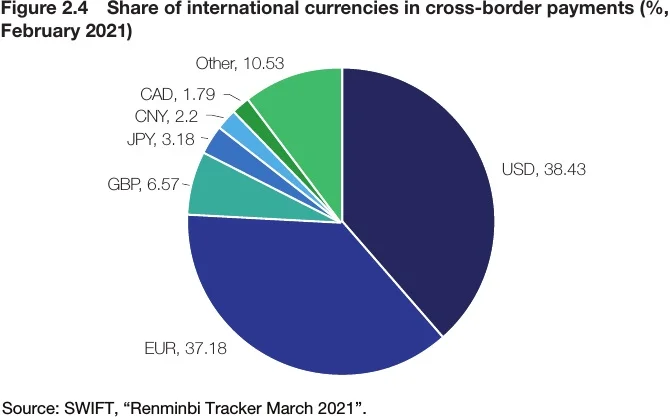

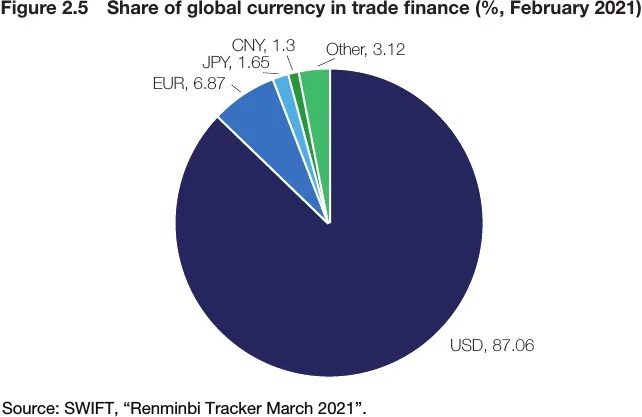

In terms of the big picture, despite the rapid expansion of the international acceptance of the renminbi in the early 2010s, the international monetary system remains a dollarised world. Nearly 60% of the world’s reserves are dollar-denominated assets; nearly 40% of international cross-border payments were settled in the US dollar in early 2021, compared with a little over 2% in renminbi (see Figure 2.4). Even for global currencies in trade finance, of which the renminbi is meant to have certain advantage given its share in global trade, almost 90% is settled in the US dollar compared with just over 1% in renminbi (see Figure 2.5). Therefore, there is still a long way to go for the yuan to be a on par with the role and status of the dollar on the global scene.

An important development in this space will be the PBoC’s launch of digital renminbi and the implications for its global status. China has been the front runner in the race to launch its central bank digital currency (CBDC) after smooth trials in several localities across the country. A digital renminbi is expected to reduce transaction costs and increase efficiency for international payment and settlement in a more secure way, thus facilitating its international acceptance and popularity.

In January 2021, Swift set up a joint venture with the PBoC’s Digital Currency Research Institute and its clearing centre, together with several other entities under the PBoC. According to China’s enterprise registration, the joint venture, called Finance Gateway Information Services Co, will handle information system integration, data processing and technological consultancy.1515 ibid. The cooperation between a key global payment system and the Chinese central bank represent a recognition of China’s advanced position in CBDC research and deployment. It is also likely to boost the renminbi’s status in the global currency system. Looking ahead, the renminbi’s path to going global will need to overcome the key issue of China’s capital controls. The milestones to watch include lifting capital control measures to the pre2015 level, and ultimately the abolishment of the capital control regime and the eventual free float of the renminbi. The former depends on the short- to medium-term robustness of the Chinese economy, especially its recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic, while the latter requires the leadership’s confidence in the longer-term stability of the financial and economic system.

Conclusion

Managing the world’s largest pile of foreign exchange reserves and promoting global usage of the renminbi represent the key challenges to China’s modern statecraft. Behind the scenes there is the rise of a new crop of technocrats within the central bank who have both vision and expertise, which is being demonstrated from reserve management to digitalising the currency. A capable and responsible Chinese sovereign investor will also contribute to the stability of the international financial markets. For the renminbi, its inclusion in the SDR currency basket was just a first step in a long journey towards a global profile. After all, convincing the private sector and international market players to accept and use the currency are crucial. Profound reforms are needed in the domestic sphere to achieve this, as it is hoped reforms at home could provide further momentum for the renminbi by making the currency more readily available, less subject to capital control and more investment-worthy. This, in turn, calls for greater credibility and policy stability on the part of the Chinese authorities.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com