A strategy for growth: China’s development initiatives

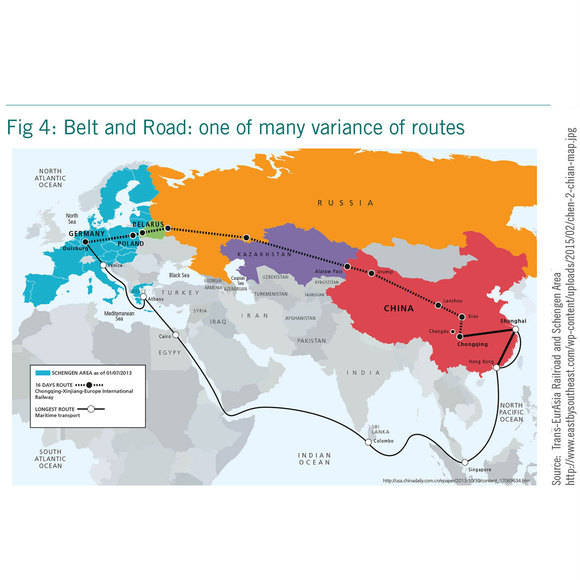

Implementation of One Belt One Road will drive global growth

The world economy needs a growth-lifting strategy, and infrastructure financing appears to hold the key. The vision of China’s leaders for the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (One Belt One Road) is winning the support of leaders throughout Asia and beyond. Two new development banks have been established focusing on infrastructure: the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). A Silk Road Fund was established in January 2015 and a China-Africa Industrial Capacity Cooperation Fund (CAICCF, $10 billion in size), designed to aid Africa’s development, became operational in January 2016. However, what conceptual framework will they formulate? This section links infrastructure investment with special economic zones for industrial upgrading and structural transformation, which provides the foundation of the One Belt One Road vision.1

Wang Yan

Wang Yan

During the past eight years, the global economy has experienced its most tumultuous times since the Great Depression. Despite the coordinated policy response of the G20 nations and expansionary monetary policy, the global economy – especially the advanced countries – has not fully recovered. The US unemployment rate declined signifciantly but the economy grew only 2.4% in 2015. The eurozone and Japan face ongoing growth challenges, with their respective central banks embracing unprecedentedly loose monetary policy. The European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan are both pursuing negative interest rates in addition to quantitative easing. But monetary stimulus is insufficient to propel a seemingly leaderless global economy towards steady growth. There is a need for a grand investment scheme and a changed mindset.

Based on the intellectual foundation of the new structural economics2, infrastructure investment looks to hold the key to long-term growth. Support for the One Belt One Road vision could motivate use of excess global savings to help development and improve employment, while also generating sound returns. It should also increase demand and jobs in advanced countries, giving them room to implement needed structural reforms. In particular, investment in bottleneck-releasing infrastructure would unleash particularly large spillover benefits.

Saudi Arabia’s support for One Belt, One Road

HRH Prince Turki bin Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud explains why his country is supporting China’s ambitious initiative

We live in turbulent times. Political instability has resulted in significant problems in various parts of the world, leading in the worst cases to failed states, violent insurgency and civil warfare. This is the debit side of the balance sheet in global current affairs.

On the credit side there are optimistic and bold initiatives to improve social and economic order by enhancing development across national borders. This includes China’s recently conceived One Belt, One Road revival of the overland and maritime silk roads.1

The naming of this major plan is a poetic echo of the Han Dynasty trading routes and is used by President Xi Jinping to describe his intention to export China’s excess economic capacity with massive infrastructural investment in the surrounding region and beyond.2 This is part of a strategy of outward direct investment, which recently for the first time exceeded foreign direct investment in China.3

The Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st century Maritime Silk Road (One Belt, One Road) has justly been described in the The Banker as "the most ambitious example of international co-operation of modern times".4 One Belt, One Road will cover territories with a cumulative population of 4.4 billion and 29% of global GDP.

To achieve its aims, China plans to invest an equivalent of $900 billion, with a further $300 billion of capital provided by dedicated funding entities. The estimated infrastructure funding gap for Asia alone, however, has been stated by the Asian Development Bank to be at least $8 trillion for the period 2010–2020.5

Finding huge sums in infrastructure finance is a major challenge. It is noticeable that early in 2015 the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank entered into discussions with the Saudi-based Islamic Development Bank over the potential for Islamic finance to serve as a source of One Belt, One Road funding.6 Here is an ideal opportunity for the stability and insurance features of Islamic banking and financial products to benefit a hugely worthwhile international project.

Islamic finance, while eminently suited to infrastructure finance, lacks standardised products and can give rise to ‘manufactured’ tax liabilities due to asset transfers, or indeed fail to meet local legal or fiscal rules. To level the playing field and draw on a huge pool of capital in many of the Silk Road Muslim majority economies, it will be necessary to systematically tackle the recognised problems. This will require central and local government goodwill, starting from China.

A standardised legal and tax code can be worked out and implemented by treaty with the Silk Road states, while the necessary work can be done by Islamic bankers to create standardised formats for infrastructure investment.

To move from ideas to action, I propose the formation of a working group to research what is needed to render Islamic finance a real and available option for One Belt, One Road project finance. It would strive to achieve practical solutions to identified problems and then move forward to seek Chinese government support to implement any necessary legal or administrative changes.

HRH Prince Turki bin Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud is a former governor of Riyadh Province in Saudi Arabia

1 President Xi Jinping announced the first element of One Belt, One Road in Kazakhstan in September 2013, expressly mentioning the historical precedent of the Han Dynasty. The maritime element was added in a speech President Xi made in Jakata, Indonesia a month later in October 2013.

2 The details of this ambitious program were set out in the National Development & Reform Commission’s March 2015 document: Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.

3 Ministry of Commerce, China; UNCTAD 2015.

4 The Banker, September 1, 2015

5 The Banker, September 1, 2015.

6 Reuters, May 2015

Infrastructure provision may also have a disproportionate effect on the income and welfare of the poor by raising the value of the assets they hold (such as land or human capital), or by lowering transaction costs (such as transport and logistic costs) they incur to access the markets for their inputs and outputs. These effects may occur through a variety of mechanisms.3

Both the macroeconomic externality and income equality benefits point to the need for public investment in providing certain types of infrastructure, because they represent either non-rival public goods as in the case of rural roads, or a natural monopoly as in the case of electricity generation and distribution systems. Without government intervention or public investment, the critical infrastructure for development would be undersupplied.

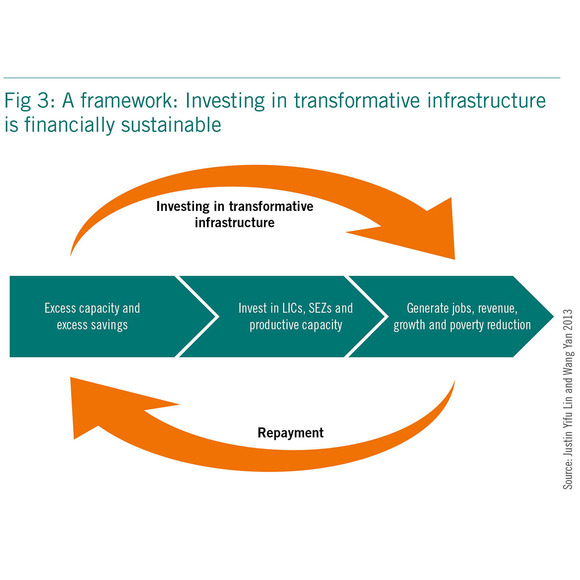

But investing in infrastructure alone is not sufficient to propel growth and generate jobs unless it is combined with productive assets and human capital. One new idea is to combine infrastructural building with green urban development, eco-industrial parks and structural transformation to generate employment, revenue, growth and poverty reduction, making the environment more sustainable and the infrastructure financially viable.4

There is a huge infrastructural funding and capacity gap in developing countries, especially in the area of renewable energy and green technology. The One Belt One Road vision and associated funds (such as the Silk Road Fund) can help ‘crowd in’ funding and increase utilisation of green technology by transforming existing cities into green cities, and building new clusters of eco-friendly industries. It will attract emerging market economies such as China and India as well as Arab countries to invest overseas and relocate some of their excess production capacity to low-income developing countries, where there is a demand. This will also help the rebalancing or structural upgrading in their domestic economies.

Improving soft infrastructure via education

Wei Shangjin explains the importance of education to securing future growth in Asia

The economy can benefit from a redefined concept of infrastructure that encompasses ‘soft' elements, such as human capital. As an investment in human capital, education is vital to economic growth in every country. Indeed, in addition to resources and capital, a large enough educated population is also indispensable for continued growth in Asia.

To improve education there is a need to look beyond quantity, to quality. This means one should focus more on whether the educated acquire all the necessary skills they will need in the workplace, including mathematics, science and communication skills. Education is not only about how many years students spend at school but also about what they actually learn. That is particularly important for countries facing a middle-income trap, which means their economies need to shift from a growth model based on cheap labour to one driven by highly educated talent.

Education poses a challenge to many Asian economies, including China, which must promote innovation while dealing with an ageing population. A shrinking labour force would threaten economic growth. If it dwindles by 0.4% every year, China will see a decline in productivity, and its GDP growth rate will drop by 0.2% every year; a 1% reduction in five years. So China's GDP growth is clearly threatened by a shrinking labour force.

China needs more investment in education, but that does not mean blindly pumping money into its education system. The country started to encourage university enrolment in the 1990s, so the number of Chinese college graduates has doubled since 2000. China has a large enough talent pool. The real problem comes from the high school education in rural areas.

Many rural teenagers of high school age choose to work instead of continuing their education. However, their professional skills cannot meet the requirements of the workplace. Others enrol in vocational schools but the quality of their education is less than satisfactory. A study by Stanford University shows vocational school students in remote areas not only fail to acquire necessary professional skills, but may even end up lacking the most fundamental cognitive and learning capabilities. That kind of sub-standard education is a barrier to sustained economic growth in China.

It is mentioned in a report by the Asian Development Bank that kindergarten education should be sufficient and accessible. Urban children who do not go to kindergarten can be homeschooled by adult family members. But their rural cousins may not receive a pre-school education of comparable quality from their possibly illiterate grandparents. The lost opportunity to acquire knowledge and skills in the pre-school stage could translate into an urban-rural gap in elementary school. Therefore, infrastructure investment should go beyond the tangible and extend to the intangible, including pre-school and vocational education. That could provide real momentum for China's future economic growth.

Wei Shangjin is a member of the IFF Academic Committee and chief economist of the Asian Development Bank

Staggering shortfalls

Infrastructure shortfalls in the developing world are staggering. Roughly 1.4 billion people have no access to electricity, about 880 million people still live without safe drinking water and 2.6 billion without access to basic sanitation. Around 900 million rural dwellers worldwide are estimated to have no access to all-weather roads within two kilometers.5 It is estimated that Asia alone will need about $8 trillion in national infrastructure and $290 billion in regional infrastructure development through 2020 and beyond.6

Estimates of the growth impact of infrastructure investment in developing countries support this notion. Caldéron and Servén7 estimate that, on average, annual growth among developing countries increased by 1.6% in 2001-05 relative to 1991-95, as a result of infrastructure developments. This effect was particularly large in south Asia, reaching 2.7% per year. Caldéron and Servén8 find that if low-income countries in Sub-Saharan African were to develop infrastructure at the same rate as Indonesia, the growth of west African low-income countries would rise by 1.7% per year. An increase in power generation in India to the levels of Israel and Hong Kong would enhance growth by 1.7%. Similarly, if Latin American countries can have the same level of infrastructure as east Asia’s middle-income countries, their annual growth will increase 2%.9

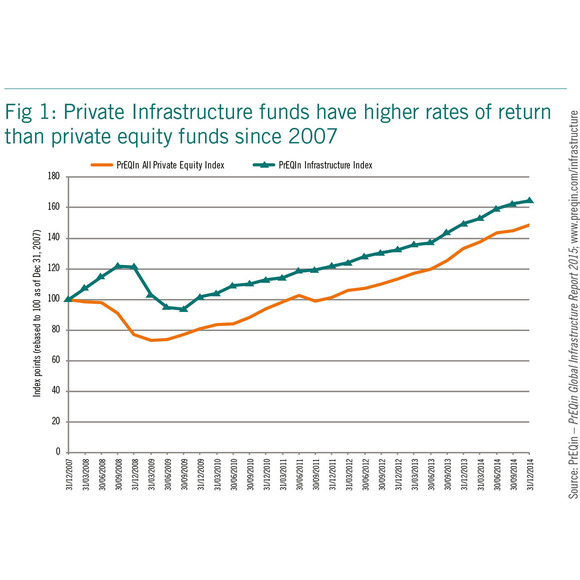

As shown in Box 1, the median net IRR for infrastructure funds across all vintages remains consistent at around 10%. Investing in the infrastructure of developing countries is riskier, but it could have rates of returns ranging from 0% to more than 100% in the case of releasing bottlenecks.10

Box 1: Infrastructure funds have higher rates of returns

Historically, infrastructure has been favoured by long-term funds due to its long-term nature and relatively stable returns (in developed countries), as well as providing downside risk protection due to the asset class's inflation-hedging attributes.

The median net internal rates of return (IRR) for infrastructure funds across all vintages remains consistent at around 10%, only falling below for funds that were investing at the time of the financial crisis.

The PrEQIn Infrastructure Index currently stands at 164.6 points and has consistently outperformed the PrEQIn All Private Equity Index since its inception in 2007 (Fig. 1).

Closing the funding gap

The World Bank estimates that annual investments of more than $1 trillion – about 7% of developing country GDP – are required to meet basic infrastructure needs in the medium term. Countries that grew rapidly – such as China, Japan and the Republic of Korea – invested upwards of 9% of GDP every year for decades. Assuming that infrastructure financing in developing countries continues at historical trend levels, there remains an infrastructure financing gap of more than $500 billion per year over the medium term.

The One Belt One Road vision and associated funds could help to close this gap. However, investing in infrastructure alone is not sufficient to propel growth unless it is combined with productive assets and human capital. There is a need for infrastructure to be associated with special economic zones or urban development to ensure structural transformation becomes self-sustainable.

Comparative advantages

New structural economics postulates that each country at any specific time possesses given factor endowments consisting of land (natural resources), labour and capital (both human and physical), which represent the total available budget that the country can allocate to primary, secondary and tertiary industries to produce goods and services. The relative abundance of endowments in a country is given at any given specific time, but is changeable over time. In addition, infrastructure is a fourth endowment that is fixed at any given specific time and changeable over time.11

New breakthroughs from the Belt and Road initiative

Wang Guogang examines the key role infrastructure can play in meeting China's economic challeges

Since the introduction of reforms, China has gained rapid economic growth, stunning the international community. However, to ensure its growth stays in the mid- and high-level range, China is facing a series of grim challenges.

First is the scarcity of natural resources. China's growth is bound to slip if it only relies on scant resources. Second, the contribution of foreign trade to economic growth is shrinking. The sluggish global economy in the wake of the 2008 US financial crisis has resulted in widespread weakness in demand. Moreover, the increasing competition in global trade and services aggravate deteriorating international trade conditions, posing new threats to China's sustainable economic growth.

Third, there is insufficient international investment globally. Though China is the country with the biggest foreign exchange reserves and the biggest creditor across the world, there is a big gap between China's overseas investment and that of the US or Japan. If this situation does not change, China's position and role in the international arena will be seriously challenged. Fourth, there is no effective mechanism for tackling the Triffin dilemma.

The implementation of the Belt and Road initiative can help solve these problems both theoretically and practically. Compared with traditional international trade, infrastructure construction initiated in the Belt and Road initiative is characterised by fixed asset investment. It plays a role in boosting foreign trade and international economic cooperation. It helps China tackle the Trans-Pacific Partnership and Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership enclosure dominated by the US, while expanding its contribution to the global economic recovery. Moreover, it helps form a new international economic development mechanism connecting investment and trade, and improves economic and social welfare in associated countries and regions.

Compared with the traditional export of production capital, infrastructure investment projects in the Belt and Road initiative are mostly projects that are overlooked by international investors but have strategic significance to the recipient country. Meanwhile, a multilateral mechanism in place of unilateral and bilateral mechanisms is more representative of international consensus and rules. This makes it easier to gain acceptance in recipient countries. Investment conditions are formed through rounds of negotiation and are thus more reflective of the consensus, interests and rights of all parties. As investment projects carried out under the Belt and Road initiative extend to countries and regions along the routes, the community will enlarge to include other countries and regions as well, creating a prospect for longstanding win-win cooperation.

Wang Guogang is director of the Institute of Finance and Banking, China Academy of Social Sciences

From the angle of land-based financing, investment in appropriate infrastructure and industrial assets would increase the value of land (a commonly accepted principle). Land-based financing offers powerful tools that can help pay for urban infrastructure investment.12 And these options have been explored during China’s experimentation with special economic zones and the infrastructure around these zones.13

Therefore, it can be proposed that: Other things being equal, a piece of land with the proper level of infrastructure is always more valuable than a piece of land without. Thus it can be well used as collateral for infrastructure development loans.

This proposition is supported by empirical evidence that infrastructure benefits the poor because it adds value to land or human capital and reduces inequality.14 Since infrastructure is often sector-specific, the ‘proper’ level of infrastructure must be affordable to the population and be consistent with the country’s existing or latent comparative advantage. Thus, market mechanisms should be relied upon to have the right relative prices and to determine which infrastructure is bottleneck-releasing. In addition, the government must provide information, identify the comparative advantages and the associated appropriate infrastructure, and facilitate this process by developing a self-discovery process by the private sector.

Therefore, it can also be proposed that: Transformative infrastructure helps link a country’s endowment structure with its existing and latent comparative advantages, and translates them into competitive advantages in the global market. Thus, it can be made financially viable. In other words, combining infrastructural building with industrial upgrading, as well as real estate development, can help make both financially sustainable. Potentially this approach has high rates of returns.

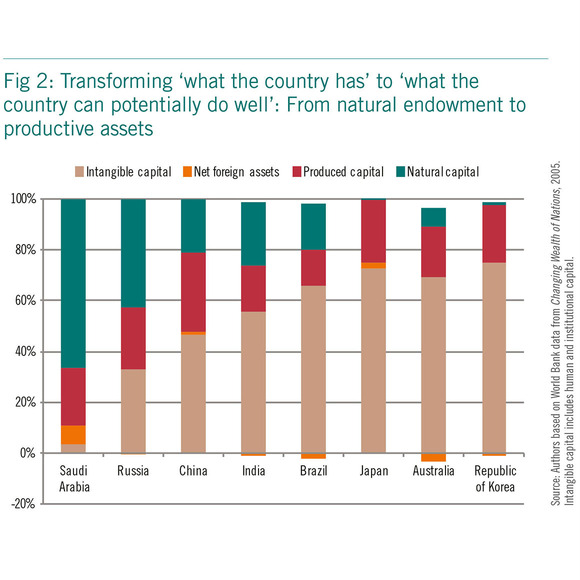

Based on these two propositions, any low-income country can have the ability to pay for its appropriate infrastructure in the long term, as long as it can develop a strategy that is consistent with its comparative advantages. In other words, we should focus more on "what these countries have" rather than "what they do not have", as suggested by Justin Yifu Lin in his farewell blog at the World Bank. See Figure 2.

What these countries need is a bridge fund in the medium to long term for 10-15 years or longer to build a productive and export base. One example shows how quickly the development results can be seen: Huajian Shoe Manufacturing Company established a large manufacturing facility in the Eastern Industrial Zone in Ethiopia, trained workers and started exporting, all within four months.15

What these countries need is a bridge fund in the medium to long term for 10-15 years or longer to build a productive and export base. One example shows how quickly the development results can be seen: Huajian Shoe Manufacturing Company established a large manufacturing facility in the Eastern Industrial Zone in Ethiopia, trained workers and started exporting, all within four months.15

China utilises its comparative advantage in construction

China utilises its comparative advantage in construction

In the IFF China Report 2015 (Section 3), we used empirical evidence to shown that China has been utilising its comparative advantage in construction and helping African countries tackle their bottlenecks. Between 2000 and 2010, 50% of China’s commitment on infrastructure was allocated to electricity and its transmission in Africa – a key bottleneck. A recent study found that China has contributed, and is still contributing, to a total of 9.024 gigawatts of electricity-generating capacity, including completed, ongoing and committed power projects.16 The impact of this investment is likely to be transformative when one considers that the entire installed capacity of the 47 Sub-Saharan Africa countries excluding South Africa is 28 gigawatts.

China has comparative advantages in constructing infrastructure. This was shown on page 65 of the IFF China Report 2015, where the graph shows that China’s labour cost in construction (at about $10-15 per hour) is only 15% of those in the industrial countries such as the US or Europe. China’s demonstrated comparative advantage is determined by the following factors: 1) existing domestic infrastructure such as highways, high speed railways, and hydropower; 2) low cost of labour including foremen and engineers; 3) ability to bring in financiers to these projects; 4) large number of infrastructure projects that have been implemented in Asia, Africa and the rest of the world. Now this argument is made stronger (see Box 2).

China has comparative advantages in constructing infrastructure. This was shown on page 65 of the IFF China Report 2015, where the graph shows that China’s labour cost in construction (at about $10-15 per hour) is only 15% of those in the industrial countries such as the US or Europe. China’s demonstrated comparative advantage is determined by the following factors: 1) existing domestic infrastructure such as highways, high speed railways, and hydropower; 2) low cost of labour including foremen and engineers; 3) ability to bring in financiers to these projects; 4) large number of infrastructure projects that have been implemented in Asia, Africa and the rest of the world. Now this argument is made stronger (see Box 2).

Box 2: China’s comparative advantage in infrastructure: High-speed railway construction

China has the world’s longest high-speed railway (HSR) system, with more than 16,000km of track in service as of December 2014.1 China built this HSR network, remarkably, in less than 10 years at unit costs lower than for similar projects in other countries. The HSR network operates with high traffic volumes on its core routes and with good reliability. This has been accomplished at a cost which is at most two-thirds of that in the rest of the world, showing its comparative advantage.

According to Gerald Ollivier, World Bank senior transport specialist: "Besides the lower cost of labour in China, one possible reason for this is the large scale of the high speed railway network planned in China. This has allowed the standardisation of the design of various construction elements, the development of innovative and competitive capacity for manufacture of equipment and construction and the amortisation of the capital cost of construction equipment over a number of projects."

Based on experience with World Bank–supported projects, the Chinese cost of railway construction2 is about 82% of the total project costs. China’s HSR, with a maximum speed of 350km/h, has a typical infrastructure unit cost of about $17 million to $21 million (100 million to 125 million yuan) per km, with a high ratio of viaducts and tunnels. The cost of HSR construction in Europe, travelling at speeds of 300km/h or above, is estimated at $25 to $39 million per km. HSR construction costs in California (excluding land, rolling stock and interest during construction) is put as high as $52 million per km.

Source: Gerald Ollivier, Jitendra Sondhi, and Nanyan Zhou. 2014. High-Speed Railways in China: A Look at Construction Costs. World Bank, China Transport Topics No. 9, July 2014.

1 China defines HSR as any railway in China with commercial train service at the speed of 200 km/hour (124 mph) or higher. By this definition, China has the world’s longest HSR network with over 16,000 km of track in service by December 2014.

2 Including civil works, track works, regular stations, yards, signaling, control and communication, power supply and other superstructure components; excluding the cost of planning, land, some of the mega stations, rolling stock and interest during construction

The benefits of special economic zones

China itself has had a favourable experience using special economic zones. The idea that industrial parks or zones can promote structural transformation as well as industrial upgrading is not new. Economists have emphasised that clusters take advantage of economies of scale and reduce transactions and search- and learning-costs.17 Agglomeration helps firms to benefit from knowledge spillovers, create a market for specialised skills, and use backward and forward linkages (good access to large input suppliers, logistics, privileged network with customers and so on). These agglomeration benefits reduce the individual firm’s transaction costs and increase the competitiveness of a nation’s industry.18

Around the world, and in particular in Africa, China has been supporting 15 or so special economic zones – or ‘overseas economic and trade cooperation zones’ – aimed to improve the investment climate and encourage direct investment into low income developing countries (see Table 1). According to detailed studies by Bräutigam and Tang (2012), in total China has jointly established six industrial zones in Africa. More than 80 companies have signed agreements and settled in these industrial zones, creating tens of thousands of jobs for African workers.

During recent years, China’s labour cost has been rising rapidly, from $150 per month in 2005, to $500 per month in 2012, and to more than $600 per month in coastal regions in 2013 (growing at the rate of 15% annually plus currency appreciation). China has an estimated 124 million workers in manufacturing, most of them in labour-intensive sectors (85 million), as compared to 9.7 million in Japan in 1960 and 2.3 million in the Republic of Korea in 1980. The reallocation of China’s manufacturing to more sophisticated, higher value-added products and tasks will open great opportunities for lower income countries to produce the labour-intensive light-manufacturing goods that China leaves behind19.

Future prospects for the Belt and Road

Economic and trade theory tell us that when countries trade with their respective comparative advantages determined by their natural and factor endowments, both sides will gain naturally from this trade.

The future prospects for the One Belt One Road initiative are bright because it is based on sound economics and trade foundation, benefiting both sides, including utilising comparative advantages, although its implementation may take as long as 20-30 years.

China has used expansionary monetary and fiscal and investment policy to overcome the contractionary pressure during two crises – the 1998 Asian financial crisis, and the 2008-09 global financial crisis – and in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Now, after seven years of resistance, the idea of building infrastructure as a countercyclical measure in a low interest environment is well accepted (see Larry Summers 2014) and is recommended by the IMF.20

In the post-2015 era, the emergence of new multilateral or regional development banks and funds such as the AIIB, the New Development Bank and the Silk Road Fund is encouraging, bringing positive energy and momentum to the world economic development arena. In a multipolar world, it seems inevitable to have different plurilateral and multilateral development banks, as well as various bilateral and plurilateral investment funds. We are cautiously optimistic that a common ground can be found for partners from the ‘North’ and the ‘South’ to work together on win-win solutions for sustainable development and world peace.

References

Aschauer, D. A. (1989) Back of the G-7 Pack: Public Investment and Productivity Growth in the Group of Seven, Working Paper Series, Macroeconomic Issues 89-13, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Asian Development Bank and ADBI. 2009. Infrastructure for a Seamless Asia. ADB Manila, 2009.

Bai, Chong-En and Yingyi Qian, 2010. Infrastructure development in China: The case of electricity, highways and railways. Journal of Comparative Economics 38 (1) (2010) 34-51.

Baker & McKenzie, 2015. Spanning Africa’s Infrastructure Gap: How development capital is transforming Africa’s project build-out, by Baker & McKenzie.

Bräutigam, D. (2010) Chinese Finance of Overseas Infrastructure, paper prepared for the OECD-IPRCC China-DAC Study Group Beijing Meeting on Infrastructure.

Calderón, C. & Servén, L., 2008. Infrastructure and economic development in Sub-Saharan Africa, Policy Research Working Paper Series 4712, The World Bank.\

Calderón, C. & Servén, L., 2010. Infrastructure in Latin America, Policy Research Working Paper Series 5317, The World Bank.

Canning, (2000) The Social Rate of Return on Infrastructure Investments, World Bank working papers, WPS 2390.

Chandra, V., J. Y. Lin and Y. Wang (2012) Leading Dragons Phenomenon: New Opportunities for Catch-Up in Low-Income countries, WB Policy Research Working Paper No. 6000

Chen, C. (2013), South-South Cooperation in Infrastructure in Sub-Saharan Africa, Working paper for ECOSOC.

Estache, A. (2011) Infrastructure Finance in Developing Countries: An Overview, EIB publication.

Estache, A., V. Foster and Q. Wodon. 2002. Accounting for Poverty in Infrastructure Reform – Learning from Latin America’s Experience. Studies in Development Series. Washington, DC: World Bank Institute.

Ferreira, P. (2008) Growth and Fiscal Effects of Infrastructure Investment in Brazil, in G. Perry, L. Servén and R. Suescún (eds), Fiscal Policy, Stabilization and Growth. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Foster, V., et al. (2010) Africa’s Infrastructure: A Time for Transformation. Washington DC: The World Bank.

G20 (Group of Twenty) (2010) The G20 Seoul Summit Leaders’ Declaration; Seoul Summit, 11–12 November, Seoul.

Guasch, J. L. (2004) Granting and Renegotiating Infrastructure Concessions: Doing It Right. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

IMF (2014) World Economic Outlook. Chapter 3 on Infrastructure. Washington, DC.

Lin, J. Y (2013) Against the Consensus: Reflections on the Great Recession. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lin, J. Y (2012a) New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development and Policy. Washington DC: The World Bank.

Lin, J. Y. (2012b) The Quest for Prosperity: How Developing Economies can Take Off. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lin, J. Y.(2011), New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development, World Bank Research Observer 2, 193–221.

Lin, J. Y. (2010) New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development, Policy Research Working Papers, no. 5197. Washington D.C., World Bank.

Lin, J. and Y. Wang (2013) Beyond the Marshall Plan: The Global Structural Transformation Fund (GSTF), a paper for the UN’s post-2015 development agenda.

Lin, J. and Y. Wang (2015) China’s Contribution to Development Cooperation: Ideas, Opportunities and Finances, FERDI Working Paper 119. Available here. Accessed December 27, 2015.

Peterson, G. E. (2008) Unlocking Land Values to Finance Urban Infrastructure: Land-based financing options for cities, Trends and Policy Options Series, Washington, DC.

UNDP and IPRCC 2015. Comparative Study on Special Economic Zones in Africa and China.

Wang, Y. (2011), Infrastructure: The Foundation for Growth and Poverty Reduction: A Synthesis, Chapter III in Volume II, Economic Transformation and Poverty Reduction: How it Happened in China, Helping it Happen in Africa, China-OECD/DAC Study Group.

World Bank. 2014. Resource Financed Infrastructure: A discussion on a new form of infrastructure financing. World Bank, Washington DC. Available here accessed December 27, 2015.

World Bank (2012b) Chinese FDI in Ethiopia, A World Bank Survey. World Bank Publications, Washington DC.

Zeng, D. Z. (2010) An Assessment of Six Economic Zones in Nigeria, in T. Farole, Special Economic Zones in Africa: Comparing Performance and Learning from Global Experience. Washington DC: The World Bank.

1 This chapter draws on source materials from joint papers by Justin Yifu Lin and Wang Yan 2013, 2015. I am grateful to Justin Yifu Lin for advice and contribution, and to Chunxu Chen and Feng Zhang at George Washington University for research assistance. Do not cite without permission from the author.

2 Lin 2010, 2011, 2012

3 Estache, Foster and Wodon 2002, Estashe 2003, and Caldéron and Serven 2008

4 Lin and Wang 2013

5 MDG Working Group, June 2011

6 According to ADB estimates. Asian Development Bank and ADBI. 2009. Infrastructure for a Seamless Asia. ADB Manila, 2009

7 2010a

8 2010b

9 Guash 2010

10 Bai et al 2010, Canning and Bennathan 2000, and World Bank estimates

11 Lin 2012b, p.21

12 For legal and typical land-asset based infrastructure financing, see policy note by Peterson, George E. 2008. Unlocking Land Values to Finance Urban Infrastructure: Land-based financing options for cities. Trends and Policy Options Series. Washington DC. PPIAF.

13 Wang Yan 2011

14 Estache, Foster and Wodon 2002, Estashe 2003, and Caldéron and Serven 2008

15 See also Sheng 2013 on Chinese OFDI in Africa, and World Bank 2012 on China’s FDI in Ethiopia

16 The Hoover Dam in Colorado, by comparison, is a two gigawatt facility, producing electricity for about 390,000 US homes, on average. See Chen (2013).

17 Krugman 1991; Greenwald and Stiglitz 1986; Porter 1990, Lin and Monga 2011

18 Lin 2012, Zeng 2010

19 Chandra, Lin and Wang. 2013

20 IMF 2014, chapter 3

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com