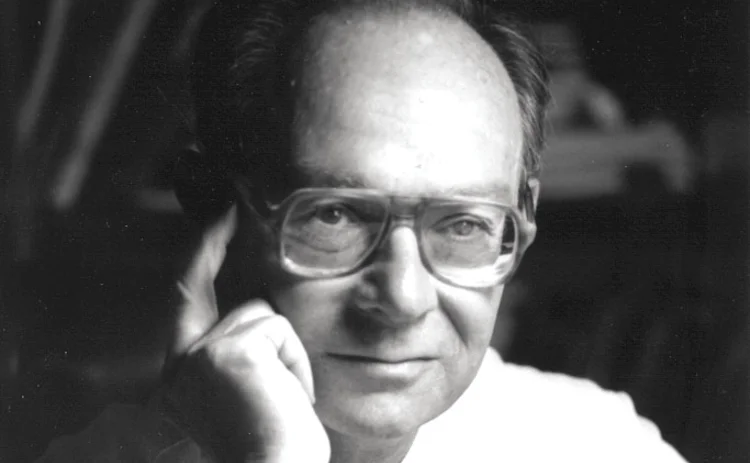

Archive – Interview: Allan Meltzer

Robert Pringle talks to Allan Meltzer about reform of international development associations; first published in February 2003

IMF reform

The report of the commission you chaired on the future of the International Monetary Fund and development banks made headlines at the time it was published, but what lasting impact has it had?

When one goes into this kind of exercise, one starts off by asking: what do I expect to happen as a result of these efforts? At least that’s what my wife asked me when I took on the job of chairing the commission: “What do you expect to come out of it?” My answer was that most commission reports end up in a drawer, but a few stimulate discussion and reform. Here we are, two years later, and the issues we raised are still being actively discussed. There is a dialogue going on and that’s good, but more than that, the IMF has actually changed. Things are done differently now.

For instance?

There are not as many lending windows, interest rates on IMF credit have been raised and there have been several changes of that kind. We will talk about recent programmes and how different they are now.

You recommended that IMF functions be slimmed down. In fact they seem to keep growing. For instance, the fund is now involved in work to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism. How do you view these developments?

We have to think of the IMF, World Bank and other development banks as a whole, and divide up responsibilities. Governments wanted these new additional issues dealt with by somebody, at an international level, but the World Bank and other development banks are weak and ineffective. The IMF is asked to undertake these extra tasks not because they are naturally part of its role, but because the World Bank does not seem able to accomplish much. It is not properly directed and it is in need of urgent radical reform.

It is a scandal that the G7 governments continue to allow the World Bank to operate as inefficiently and ineffectively as it does

You obviously feel strongly about this.

Yes, I do. It is a scandal that the G7 governments continue to allow the World Bank to operate as inefficiently and ineffectively as it does. If we are to win not only the war on terrorism but the peace, we are going to have to do a lot better in the Middle East and elsewhere about problems that are in the bank’s domain, but which it does not seem capable of managing effectively. Our report demonstrated how much of its core task the World Bank fails to accomplish. It takes on many other tasks where it can contribute little. I tell you frankly, when I started work on the report, I thought the bank was a good and effective organisation. I came out with a very different view, and one which is much more accurate.

So you agree with those who accuse it of ‘mission creep’?

Mission creep? It’s galloping! James Wolfensohn has an enormous appetite for new activities, but he tries to do them all on the same budget. In many of them the truth is the World Bank has contributed little.

So what is the way forward?

The first step should be an independent performance audit. After that we will have better information about what the bank accomplishes. Then there has to be a restructuring of the entire World Bank group and the other developments banks.

The latest announcement from the Bush administration and [Treasury] secretary [Paul] O’Neill on International Development Association (IDA), saying the US will increase funding for IDA loans if the bank’s performance improves [and] goes in the right direction, but does not go far enough. The main thing to begin with is that there has to be an audit by outside experts to identify what the bank does well, what it does poorly, what tasks it can accomplish and how can we reorganise it, so it can do a few things well.

The fact is the World Bank is now a very small part of the overall flows to developing countries and of the international capital market. They have never come to terms with that. They need to focus again on those things they can do that the market won’t do.

You mentioned the IMF has changed. What is the evidence for that?

Well, look at Turkey and Argentina; then look at this vexed question of the private sector and how to get it to bear its fair share of the costs of mistaken lending decisions.

There are many things about the Turkish programme I do not agree with, but the fact is that Turkey was made to enact legislation to push needed reforms through before the IMF gave them the money. In the past, countries just had to promise to do what was required – and often reneged on these promises. This was true of Russia, for instance – all they had to do was promise; there was no incentive for them to do what they promised. That’s the way a lot of these programmes went. I regard what happened in Turkey as a step forward.

The market has now witnessed a series of failures – in Russia, Ecuador, Ukraine, Argentina – of sovereign debt crises where the IMF did not step in. And the market will draw lessons from that and the risks they undertake. The moral hazard problem has been much reduced

In the case of Argentina, the country was allowed to default. It is the biggest nominal default in history. True, the IMF threw money at them in December 2000 and August 2001. That was a mistake. True, the needed restructuring would have been much easier if it had taken place from February 2001, rather than from February 2002, but just look at what has happened. The IMF is insisting Argentina comes up with its own plan, that it has to be coherent and credible. This is very much in the spirit of the commission’s report.

Also, the whole discussion that went on for so long about how to bail in the lenders has been largely resolved. People have realised, finally, that if you don’t bail lenders out, they are bailed in. The market has now witnessed a series of failures – in Russia, Ecuador, Ukraine, Argentina – of sovereign debt crises where the IMF did not step in. And the market will draw lessons from that and the risks they undertake. The moral hazard problem has been much reduced.

So the system has changed?

Yes, it has changed. We have gone from a system where lenders charged 10%, 20%, up to 50% spread, but did not take the risks. Now we have had some failures, they realise the risks are there. Risk and reward are now much more closely related. Of course, it is very difficult to judge how much of that was due to the commission’s work, but we highlighted the issues. The major reason was the change in the leadership of the IMF and at the White House. They read our report and are now implementing parts of it – that’s progress.

In our last issue, Stanley Fischer mentioned he thought precautionary lending was an excellent idea, embodied by the fund’s Contingent Credit Line facility (CCL), but he expressed reservations over the notion of pre-qualification. How would you like to respond to these comments?

Well, the managing director, Horst Kohler, would like more use to be made by the fund of the contingency credit line, with countries agreeing in advance to conditions for lending and then gaining access quickly to credit, if and when a crisis hit. One obstacle to this facility being used lies with the fund’s bureaucracy; they are afraid to make a commitment in advance to lend.

One main problem has been that countries have been led to believe they would always be helped by the fund, so the incentive to go through the process of meeting the conditions to allow you to pre-qualify for assistance has been absent. The situation may change quickly once governments realise that in future they will not necessarily be rescued. The fund also needs to demonstrate to borrowers that if they adopt the CCL programme, they will get better interest rates on their borrowing and better access to international capital. The CCL will serve as a seal of approval. Countries have to see the benefits to them of adopting the programme. Then the finance minister of the country involved can ‘sell’ it internally.

Argentina

Who has let down the Argentine people – the Argentine government or the IMF?

Look at the story. When I was in Argentina in April 2001, [Ricardo] Lopez Murphy had just gone out of office as finance minister. He wanted to make spending cuts, but the government did not agree. The coalition broke apart. Within four months, because they did not get any additional IMF assistance, Domingo Cavallo was moving towards a zero deficit month by month, and he reduced spending much more drastically than Lopez Murphy had suggested. That was progress. It took place because the IMF did not give (much) more money. It didn’t bail out Argentina or its creditors. August was a retreat, but in the autumn of last year, the IMF was again rightly insisting that Argentina keep to its promises and targets.

So what has been accomplished by this tough line?

We have established: first, that a major country can default, can be allowed to default; second, that this can happen without causing contagion in the markets; third, we must now get Argentina back to the path of sound policies and sustainable growth without granting large sums; and fourth, there must be a meaningful debt restructuring.

They are not going about it the right way right now, are they?

Argentina is floundering around and making a lot of mistakes.

What lessons are there be for currency-board exchange rate arrangements as a result of the crisis in Argentina?

Anna Schwartz wrote a very good essay on currency boards several years ago. She showed they worked well for UK colonies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This was because the colonies were subject to UK colonial law, where they could not run budget deficits, where the banks in the colonies were generally branches of London-based banks [and] where the parent bank would take responsibility for any loan losses by its branch. This system worked well.

The currency board works well now in Hong Kong. In Argentina, they violated a fundamental rule of the system. They ran large deficits that they financed abroad on the international capital markets. They took on an unsustainable debt burden and the debt-service costs amounted to a large percentage of their export earnings. They also entered into a trading agreement with a country (Brazil) that had a floating exchange rate while Argentina had a fixed rate. That became a problem.

International bankruptcy proceedings

Anne Krueger recently came out in favour of the idea of an international bankruptcy proceeding for over-indebted countries. Is this really a good idea? Could emerging market countries be persuaded it is in their interest?

This is one of those ideas that will never happen. First, it is much too hard to implement. Second, it changes the nature of contracts in such a fundamental way that lenders will not want to enter into such agreements. Under this proposal, the IMF, itself a party to the contract, can decide that borrowers will be allowed to default against all other creditors, but not against the IMF. Would you want to sign such an agreement? It would amount to a huge increase in the authority of the IMF over international capital markets. They decide when a country should be in default. The IMF would have a lot more power than a sensible lender will tolerate. Lenders would have to compensate for the increased risk by widening their margins or withdraw from that market. It won’t work.

So what further improvements can be made?

One step is that developing countries will have to allow foreign banks to have a far bigger role in their financial systems. In Argentina, it was remarkable that despite all the damage done by its government policies, until the very end there was no run on the banks because of the foreign banks there.

In the end, the run was not because of the insolvency of the foreign banks, but because people were worried about what the government was going to do to their money. Depositors feared devaluation, so they took their money out of the country. This caused a collapse of the reserves of the system. People feared a default by the government on its debt, followed by the end of the promise to exchange dollars for pesos on a one-to-one basis.

Another improvement in the system will come through much heavier reliance on foreign direct investment as a source of capital, and much less on bank and bond finance.

Japan

What is the best policy option for Japan?

Continued monetary expansion and depreciation of the yen. Of course, monetary expansion would be more effective if the banks were more willing to lend. The bad loan problem needs to be cleared up, but that problem should not deter the Bank of Japan from expansionary policies. Part of the bank’s problem is that asset prices have fallen and the economy is weak. Stopping deflation will help improve the banking system.

But, as exports are only 10% of GDP, wouldn’t the devaluation have to be very large to have much effect?

Growth in exports itself will not bring about a miracle cure, but it will help. As exports rise, inventories will stop falling, [and] investment and employment will increase at home.

What about the growing opposition to the policy of yen depreciation from other Asian countries? The governor of the People’s Bank of China has recently been very critical of Japanese exchange rate policy.

I am constantly surprised that central bankers do not understand the alternative to exchange rate depreciation is deflation. In Japan, exchange rate devaluation is an alternative to further deflation. Japanese costs and prices have to be brought into line with world prices. It is only a question of whether the price level falls or the nominal exchange rate depreciates. Either way, the real exchange rate has to adjust. Both are harmful to neighbours, but also unavoidable. Depreciation has the advantage of being quicker.

Can fiscal stimulus help?

No. Repeated fiscal packages have done nothing for growth and created a serious long-term debt problem.

US monetary policy

Is American monetary policy too loose or too tight?

Far too loose. If you look at any of the monetary aggregates, they are growing by 8–10% a year or more. Again, the Fed has swung from famine to feast: in the summer of 2000, money-supply growth was too low. Now it is far too high.

Inflation or monetary targets?

Do you think inflation targeting or price stability should be the objective of monetary policy?

Well, any monetary or inflation rule is better than none. Inflation targets have weaknesses. Policymakers have to distinguish between changes in inflation that are monetary, and likely to continue, and one-off changes in the price level that do not cause persistent increases in inflation. Suppose we had another oil shock; would you want central banks to send the economy into recession in order to keep inflation within the target range, or would it not be better to adjust to that once-for-all price change and go on from there?

Until 1945, every war was followed by deflation and recession. This was because governments wanted to go back to gold at the old price. The main point of a monetary rule is that it prevents central banks from causing inflation by monetary policy.

This article was first published in Central Banking journal, Volume XII, Number 3, February 2003.

Further reading

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com